ANDROGENIC LITERATURE REVIEW Vol. 4: Vaporfornia

when incelcore doesn't quite work

Like any other sufficiently involved work of art, a novel is inherently an egoic work.

Because any kind of honest work comes out of a deeply personal space—even if it is not directly derived from an author’s own experiences—literary criticism almost invariably crosses over into a sort of oblique form of personal criticism. The reason for this is not characterological. A narrative work is an extension of the self: it’s like the recombinant output of the brain as a large-language model. Our intuitions about the inherent difficulty of extricating the art from the artist are not inherently wrong. The conduit out of which a story is born is naturally shaped by the conduit itself.

(Yes, I realize I’m contradicting what I previously said about this. A work of art is both the product of the artist and transcends the artist at the same time. Both of these statements are equally true; the universe is not a binary logic puzzle that can sit comfortably in your brain).

So, in order to produce a book, you take a human being and you feed them words and experience, and on a long enough timeline—for some people and in some cases—you will get a novel out of the other end.

An honest book is extruded from the person in the same way that honey comes a bee; he or she simply cannot help themselves from working. This is particularly true in an age where the modal writer either lives in abject poverty or makes zero money from their stories. For this reason, the vast majority of us are beholden to what can only be described as a compulsive behavior.

The first time I received a harsh negative critique of my novel was almost immediately after it was released. After 10+ years of intermittently and obsessively working on my debut, it is hard even in retrospect to articulate the level of psychic deflation I experienced in the wake of my initial publication. Within the span of about 48 hours, my perception of my own abilities oscillated in a violent sinusoidal pattern as I bounced between positive and negative feedback from friends and strangers alike, going from elation to deflation and back again several times.

Thus, it is with great empathy that I approach the work of any writer, particularly those who have done it on their own and without the institutional backing and approval of a traditional publisher. I don’t at all care about savaging the work of someone established or notable, but with anons or more marginal figures, if I don’t like the book, I simply try to avoid talking about it.

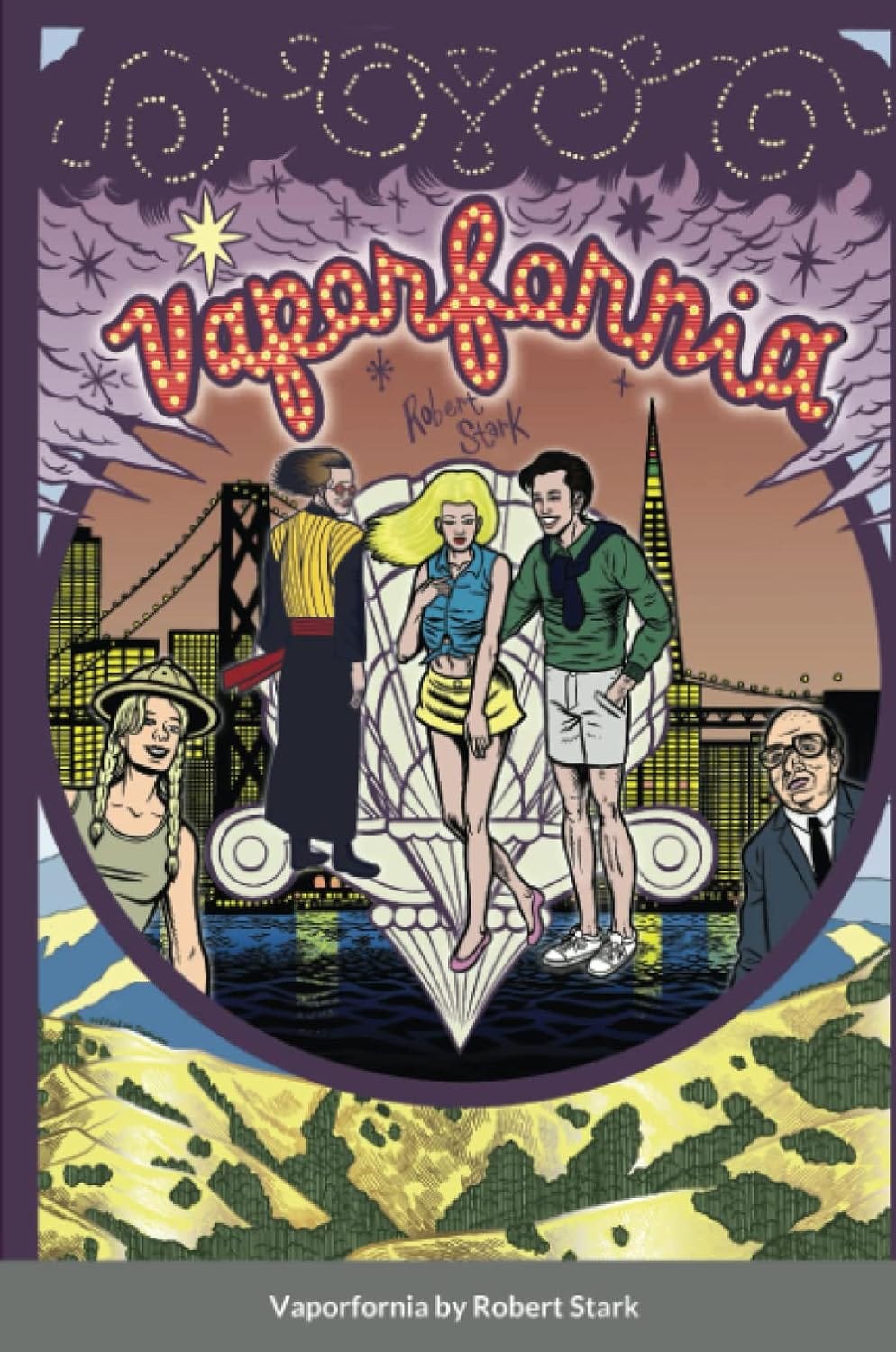

Several months ago, Robert Stark asked me to review his novel, Vaporfornia, on my SubStack. We’ve exchanged some limited back and forth messaging, and because I promised to see the review through to completion, I am compelled to release this piece.

The plot of Vaporfornia is a chaotic, loosely connected series of increasingly comic and absurd situations that is meant to be read as a satirical comedy, but the essence of the book is that it’s a story about a contemporary incel. Even with a close reading, it’s often a struggle to understand exactly what is happening and why, but the reader isn’t really meant to keep track of these events as causally continuous, but rather more as a pastiche of wild and crazy scenes that have been somewhat arbitrarily cobbled together.

As I’ve written before, I think the subject of the incel is a deeply interesting figure, ironically, because the modern incel possesses a certain kind of novel intersectionality: he is the confluence of multiple intersecting social, political, ideological, and religious trends.

For this reason, I am always partial to reviewing any kind of modern incelcore literature with a favorable lens. This is especially the case since I know from personal experience how difficult it is to write something that confronts the base reality of male interiority without holding back or flinching.

Stylistically speaking, I do wonder if Stark made an attempt to closely mimic the bare-bones prose of Elliot Rodger in his manifesto from 2014. There’s a superficial similarity in narrative voice between the two of them, but whereas Rodger’s manifesto is a shockingly literary account of profound narcissisim and psychic breakdown, Vaporfornia fails to achieve any modicum of psychological realism or narrative, voice-driven momentum.1

Even when viewed with a satirical lens, the portrait of its protagonist lacks any kind of interesting psychological pull and comes across more like someone matter-of-factly narrating a sequence of barely-coherently-connected and otherwise implausible plot events in which it’s repeatedly revealed that the character’s experiences in a particular scene were actually a dream or a simulation.

The problem, over and above all the other problems with the book, is that none of the sentences really work.

To get a sense of the prose style, I’ve quoted some longer paragraphs here:

I’ve been rethinking everything I learned about racism and White privilege in school. The thing is capitalism creates a scarcity mindset and forces us all to compete for scarce resources. DCR is wrong that woke capitalism and criminalizing hate speech will end inequality and Blackstone has been saying that giving everyone a monthly check will ease racial tension. I mustn’t feel guilty about bigoted thoughts and slurs and realize that I too am also a victim of the neoliberal system, and that capitalism is responsible for any horrible racist thoughts that I may think in times of scarcity.

Here’s another:

I wish I could hunt down and murder every single adult who told me I could amount to great things when I was a boy. All lies. Our entire society is based upon the big lie, the so-called American dream, to keep the workers working and the consumers buying more junk. Take the Black Pill and realize that there’s no movie ending, no girl from my dreams there waiting for me once I ascend, and there’s no fucking oasis. All my visions were just a cope: fantasies of something I will never experience. Even if I had studied hard, got into a good school, and careermaxxed.

So, why this might reasonably reflect the style (and therefore conscious experience) of some flavors of American incels, the style is too droll to keep me engaged as a reader.

There’s a version of this book that might work much better, but that version would have to be written in a completely different way. Relative to the narrative architecture of the story, which swings wildly from one absurd situation to another, it would be very difficult to execute well for a writer of any caliber.

If I were to distill my critique of the book into a single idea, I’d borrow a quote from Ursula K. Leguin which was recently mentioned in Tooky's Mag’s literary podcast:

Many readers, many critics, and most editors speak of style as if it were an ingredient of a book, like the sugar in a cake, or something added onto the book, like the frosting on the cake. The style, of course, is the book. If you remove the cake, all you have left is a recipe. If you remove the style, all you have left is the synopsis of the plot.

This is basically the insurmountable problem of the novel: it’s not written well on a sentence-by-sentence level. By extension, it’s not written well on the level of a paragraph, on the level of a scene, or on the level of a chapter. Because the sentences aren’t there, the rest of the narrative superstructure can’t possibly hold together, and that is aside from the fact that essentially every character (except possibly the protagonist) trends toward reductive caricature.

In my view, even in literary satire, you can’t lean too hard into caricature—it’s not an excuse to write flat characters.

There are a couple of scenes in the book that did merit some degree of laughter, and Stark is sometimes able to capture short spurts of absurdist humor reasonably well. There’s a particularly funny scene where the low-status, socially maladjusted (and possibly autistic) protagonist is inexplicably able to secure a date with a young Asian woman, and watching him completely derail the opportunity was a fairly hilarious portrayal of a WMAF-relationship stereotype which reminded me of a blog post from 10+ years ago on Chateau Heartiste (formerly Roissy in DC) that I can no longer find.

Another scene sort of reminded me of a 4chan post somehow brought to life:

The other Chads ignore him, cheering on as the incels beat up Meschel and the other studio executives, investors, and journalists. One guy who must have hacked into the loudspeaker plays some fashwave. The Chads take it as an opportunity to take off their polos and start grinding up against the girls. The incels look pissed. One incel screeches, “you richfags don’t support our cause. You’re just bored with having everything and want an excuse to rebel!” The Chads ignore him and start making out with the girls as the incels just fondle themselves to the spectacle from the sidelines. One female journalist, panicking frantically, as she obsessively says #MeToo over and over.

Partly it’s possible that I’m being skewed by my own bias: rare exceptions aside, I’ve never really liked absurdist humor, only ever appreciating literary satire up to the level of a realistic black comedy-of-manners, so I can still see a certain type of reader still appreciating this book.

Where Stark does succeed is in departing from the traditional tropes of the incel-as-character and at least making an attempt to deliver a somewhat fresh characteriztion.

Thus, while the narrator’s voice superficially sounds like Elliot Rodger, he is far less angry and much more neurotic, continually anxious about his true self being discovered and often earnestly trying to be prosocial and fit in. You can see an effort from Stark to integrate somewhat atypical or otherwise syncretic political views and while many narration-based-segments or verbal exchanges between characters come off as didactic, the positions that they are arguing for are so varied and chaotic that it doesn’t come off as particularly ideological.

At times, the portrayal of race and racism through a decidedly absurdist lens does kind of capture the hilarious insanity of California culture in a way that reminded me of the radio stations or over-the-top characters in the Grand Theft Auto video game series.

Seemingly at random, the book produces brief clips like this:

Their leader proclaims “we are GAJOCAMI; Goyim Against Jewish Oligarchic Control And Mestizo Invasion. It’s pronounced ‘Juajocami.’

To the extent that garden-variety anti-Semitism can be mocked like this, it is indeed funny, and a sprinkling of these bizarre comic spectacles does truthfully converge on the sheer madness and wackiness of America:

At other times, the attempt at absurdism falls much more flat and just plays out in cheap racial caricature that comes off as totally pointless:

Panicking, I get off my bike as the guys start approaching me with a look of intimidation. Their leader asks, “what you doin here White boy?” I try to avoid making eye contact and continue on my way. Their leader shouts “listen ese! You on our turf!” I explain “I just moved to the area. Now please, I have to get home.” One guy interrogates me, “you moved into one of those new mansions ese?” I nod yes. He says “you on stolen land. This is Mehico. Occupied Territory. Those old rich White fools come in and treat us like slaves. Without our labor they’d be livin in trailer parks.” I flinch as he gets close to my face. Their leader proclaims “We the Harnizos! You best be respecting our turf.”

Ultimately, for incelcore literature to work, it must at minimum be executed with a strong sense of style and voice.

Beyond that, it has to avoid cultural repetition by presenting either an innovative social or philosophical critique or analysis of modern inceldom and what it means.

The danger of a niche like androgenic literature is not that it won’t trend toward honesty, but that that it will become overly reliant on trickery or transgression, which, over time, simply becomes repetitive with excess.

While Vaporfornia doesn’t quite fall into the second trap, it does arguably fall into the first.

For those of you who have not read Rodger’s manifesto, the context here is that it’s actually about 90% a narrative account of his life and 10% an ideological project or argument in the traditional sense of what you’d expect from a more historically standard mass shooter or terrorist.