The incel as a literary subject

Thoughts and general commentary on the Tooky's Mag review of 'INCEL: A Novel'

I very much enjoyed listening to the guys over at Tooky's Mag review my debut novel, INCEL, on the Sidebar literary podcast.

I’ll start with some continuity/versioning issues, and then transition to some broader thoughts on their response to my novel, which I felt were quite deeply considered.

Overall, I felt it was a great discussion, and it’s clear to me that the Tooky’s guys will soon join the ranks of Dan Baltic & Matt Pegas’s podcast in the upper echelon of the spoken-wordcel commentariat that now orbits a new sphere of alternative (and androgenic) literature.

SPOILERS BEGIN

There was quite a bit of confusion about the versioning of the novel in the review, which was, of course, entirely my fault.

I actually sent them three versions with three slightly different endings:

Ending 1 [EDITION 1]: (Capitalisimo read) A prolonged conversation between anon and his neighbor’s widow.

Ending 2 [NEVER PUBLISHED]: (Dave and Gabe read) An ending where the conversation is completely cut and anon only watches the widow from a distance.

Ending 3 [EDITION 2, OUT NOW]: (no one read) An ending that’s a hybrid between 1 & 2, where anon imagines a conversation with the widow after remembering a blog post he read earlier in the day, in which she recounted a story about her husband dying of cancer.

There are various prose improvements separating the editions in addition to what I wrote above, but the ending is the only important narrative aspect of change.

The other point of confusion is the race of Elizabeth. I can confirm that, canonically speaking, she is revealed to be Asian (with dyed blond hair).

SPOILERS END

Let’s start with a question.

Why is the modern incel a compelling literary subject?

Much like his lineal patriarch—the millennial pickup artist—I would argue that the incel is an interesting literary subject because he possesses a reductionistic, mechanistic view of the human being, and any fundamentally mechanistic account of the human being provokes deep, unremitting existential horror in any psychologically normal person.

All three commentators—Capitalisimo, Gabe, and Dave—correctly understood this as the substantive territory of the story.

Part of the veridical experience of existing as a human being, part of its evolved phenomenology, is deep ignorance about the continuous stream of computation that floats deep under the waterline of conscious awareness. Importantly, the more intuitive an experience is—the more presence that any given moment evokes—the more disturbed we are by the computation underlying it.

This is nature’s will: man is a machine who was never meant to see his own gears.

Think of something like love or infatuation. Most of us have some formative, deeply meaningful experiences centered around these emotions. At the same time, we also know that these emotions are produced by complex systems that recognize patterns in potential mates and activate certain responses commensurate to the other person’s apparent level of reproductive value.

Some of you are laughing at this. Yes, the latter explanation does sound like psychopathy—one of the theses of the novel, is that, in some sense, science is psychopathy. Under scientism, to understand is to achieve complete distance from the thing being understood. In conveying this point, I’m merely recapitulating widely accepted concepts from evolutionary psychology and cognitive science. In academic terms, I’m not relating anything controversial.

What the incel realizes, dear reader is that the once you accept that love and intimacy and meaning are undergirded by biological computation, you have built a very powerful gateway into meaning collapse, anomie, and nihilism.

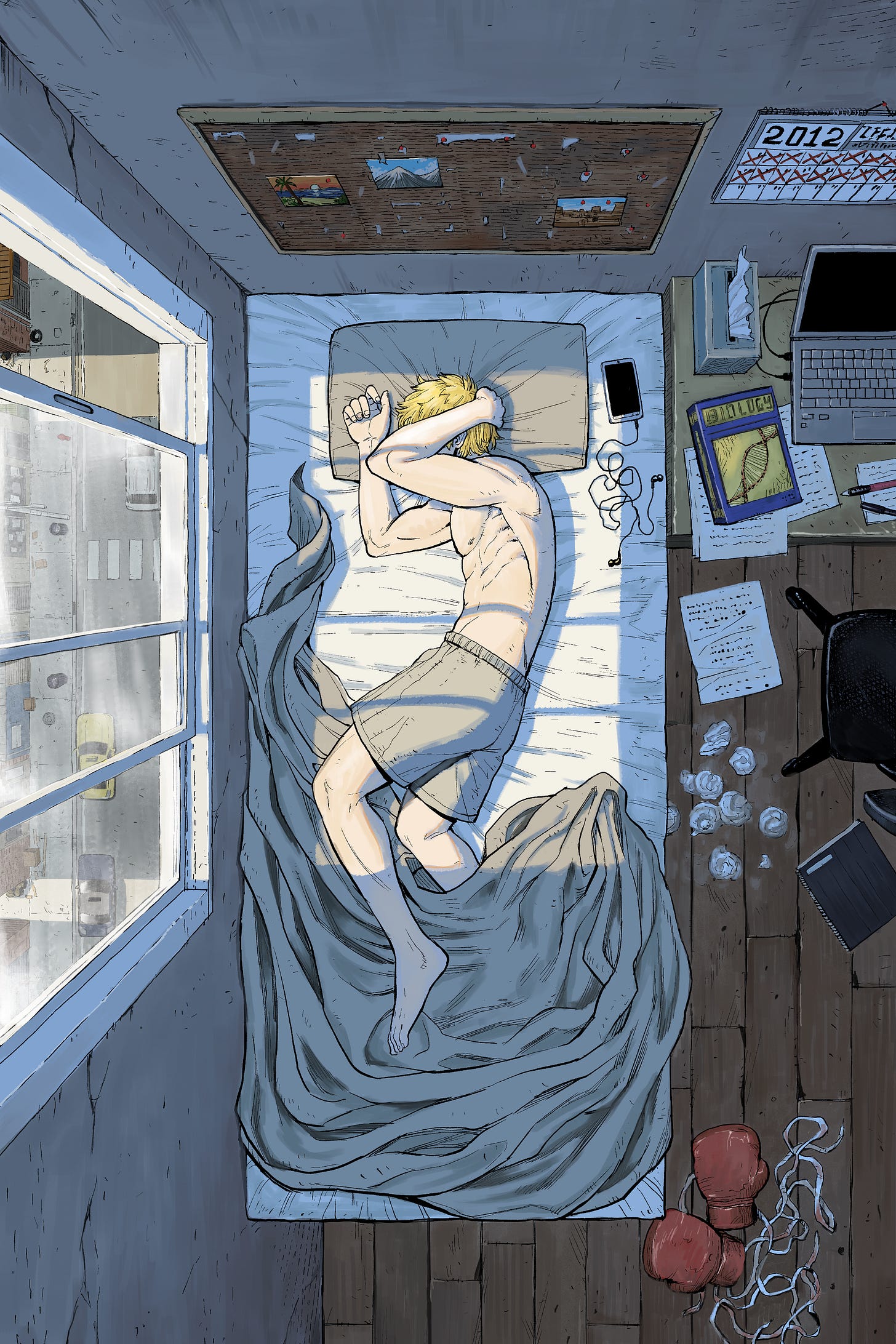

And so—the modern incel—“the quintessential subject of modernity,” is a young man who has searched for meaning but found it absent. If he is alive right now, he has lived through a late-USSR style collapse in nearly every possible dimension of meaning: religion (killed by science), state (killed by oligarchical financialization), community (killed by industrial capitalism), art (killed by homogenization), family (killed by the preceding three) and lastly, love (killed by inceldom).

Wealth does not count as a sufficient source of meaning.

In modernity, the only ritual of masculinity that remains for the young man is to have sex. In effect, it is the main remaining prerequisite for a successful transition into adulthood (reproduction is no longer required). If he is unable to achieve this, there is essentially nothing left that is socially prescribed for him apart from wealth accumulation. This dynamic exists against a background of intense atomization and loneliness that is already a feature of our urban societies.

That is why the incel is a compelling subject of literary study.

Notice that incels refer to women mechanistically, as “femoids/foids.” Notice, further, that they construe themselves mechanistically, as a collection of physical measurements, external status markers, and so on. Reductionism, instantiated in a nihilistic extension out of evolutionary psychology and biology, is the true element of “bio-materialist horror” that the incel provokes in the average person.

(I like the term “bio-materialist horror” quite a bit, actually—I believe the academic Louis Betty coined it to describe the genre in which Houellebecq has been writing).

Compounding this is the problem of free will, which cannot survive a biological account of the human brain under any coherent definition that doesn’t constitute a philosopher’s word game.

Similarly, the incel’s patriarchal forebear, the “pickup artist,” naturally evokes similar feelings of the void. What was most disturbing about (now-dead) pickup artistry wasn’t merely the way it diverted itself around different kinds of sexual morality in order to reach human instrumentalization. What was disturbing about it was the fact that the mere possibility of psychological manipulation around something as central as love or intimacy suggests that human beings are fundamentally and inescapably mechanistic to our core.

Now, of course, I do not personally subscribe to either of these extreme accounts of personhood. Even in regimented, so-called “systematized” approaches to human relationships, whether intimate or not, irreducible aspects of humanity are always breaking out of these artificially imposed constraints. The lines drawn by these ideologies, in practice, cannot ever subsume human agency or vitality.

Anon, even in spite of himself, cannot escape his own humanness—and eventually, he realizes this.

But! For many, it is easy to believe that they can.

The incel is the apex instantiation of scientism as a worldview.

That is why he finds himself, so often, in hell.

A couple of notes on specific comments that stood out to me:

Gabe said that “The philosophy of Nick Land haunts this novel in a weird sense. The idea of an implied telos for evolution…”

In hindsight, I am astonished that I didn’t actually substantively read Land prior to writing this novel (instead, I read similarly nihilistic stuff by the philosopher Alex Rosenberg).

I recently finished Xenosystems Fragments, and the convergent themes are certainly there, no doubt.

Land approaches horror from an evolutionary lens, and the one central Landian idea that made it into the book came out of his famous post, “Hell-baked,” which I came across via a Zero HP Lovecraft tweet (it’s a short blog post about the bio-materialist horror of evolution driving suffering). It’s, without a doubt, one of the most potent pieces of writing I’ve ever encountered.

Caveat: this question of the problem of suffering has obsessed me for many years, but I think the Landian interpretation is more of a rhetorical overlay that sits on top of a standard evolutionary account of the biological evolution of pain. Still, it’s a brilliant rhetorical overlay.

Dave and Capitalisimo talked about the afterword as being a mistake, as hurting the book as a work of art and revealing the story as being somewhat didactic, possibly confrontational, or attempting to instrumentalize the reader. I felt this was a very interesting discussion point.

I think on net this is a reasonable critique of the afterword, which I assumed would be somewhat polarizing, and I can certainly see the irony in me endlessly complaining about didactic literary fiction and then releasing an afterword that will inevitably come off as didactic itself. Fair enough.

There is a good rule of thumb in fiction: “Resist the Urge to Explain” (“RUE”). I cannot remember where I first read this, but I think it is equally applicable to the back matter of a novel, not just the narrative text. In writing the afterword, I made the mistake of (a) revealing too much of myself, and (b) attempting to explain something that was, in retrospect, already sufficiently clear. Fundamentally, my novel does have a very clear theme—Capitalisimo called it “touch grass”—and that core theme is merely that meaning in life is irreducible and experientel. This is, at root, a pre-ideological claim: a spiritual orientation toward living, and couching it in political language probably just polarizes what could be a universal message that each person can readily interpret for themselves. In hindisght, I probably unnecessarily feared being misunderstood as a writer, and this fear was not ultimately based in reality. The core theme is glaringly obvious to any reader and there is no need to attach a retroactive explanation of how the book was crafted. Instead of rewriting the afterword altogether, I will probably just cut it out altogether because I’m too lazy to rewrite it and I suspect it’s extraneous.

Dave’s framing of the chapter where anon gets into an argument on the internet surprised me somewhat. The way this was crafted, this scene was meant to display how mockery, smarm, condescension, and so on, only serve to harden the views of the recipient—to reveal this type of dialogue as insulting and counterproductive. The character of ‘RaytheonRespecter’ was a parody of a self-insert, not an attempt at confrontation, hence the meta-commentary in the scene about confusing art with propaganda—in effect, the book laughing at itself, and so on.

I thought the commentary on the subject in race in the novel was interesting, but I will save my response to that for another article about literary fiction and its role in racial power fantasies.

The fear and loathing of the incel is not because he's a loon but because he might be right.

Found your Substack via your comment on "Asian American Psycho" at Salieri Redemption. Have you read "Sinking" by Yu Dafu? It was the first thing that came to mind when I saw this title, "The incel as a literary subject", just a click away from "Asian American Psycho". It's a short novella from the 1920s about a Chinese incel in Japan that explores the incel psyche very well ("I'll take revenge on them all" internal monologues included). It's very much about "shame / masculinity / radicalization" from your bio, especially shame stemming from the protagonist's identity as a Chinese man/China's geopolitical status a century ago. Much has changed since then, but in a way, I think this novella still reflects some realities today. Seeing that you're a Chinese-American interested in these themes, would highly recommend if you haven't already read it.

I like your writing from what I've read on here, so definitely will be checking out your book as well.