In spite of ourselves: the immoral artist and the production of beauty

should we demand moral purity from authors?

"I don’t think we can separate the art from the artist, nor should we need to. I think we can look at a piece of art as the transformed or redeemed aspect of an artist, and marvel at the miraculous journey that the work of art has taken to arrive at the better part of the artist’s nature. Perhaps beauty can be measured by the distance it has travelled to come into being.

That bad people make good art is a cause for hope. To be human is to transgress, of that we can be sure, yet we all have the opportunity for redemption, to rise above the more lamentable parts of our nature, to do good in spite of ourselves, to make beauty from the unbeautiful, and to have the courage to present our better selves to the world.

The moon is high and yellow in the sky outside my window. It is a display of sublime beauty. It is also a cry for mercy — that this world is worth saving. Mostly, though, it is a defiant articulation of hope that, despite the state of the world, the moon continues to shine. Hope too resides in a gesture of kindness from one broken individual to another or, indeed, we can find it in a work of art that comes from the hand of a wrongdoer. These expressions of transcendence, of betterment, remind us that there is good in most things, rarely only evil. Once we awaken to this fact, we begin to see goodness everywhere, and this can go some way in setting right the current narrative that humans are shit and the world is fucked."

One of the things I do after I’ve read a novel that I like is to look up the author and immediately locate their Twitter feed. I’ll then scroll through their Twitter and evaluate their various political or cultural opinions to try and determine what they think about various topics that are of personal interest to me. This is a sort of compulsive behavior driven by simple curiosity and perhaps also a desire to have my own beliefs mirrored back to me by someone that I am hoping to admire.

Usually this process is neutral to mildly disappointing (but never upsetting), and my reactions are as follows:

“Oh, he’s a [shitlibbed] moron.”

“Oh, he’s a PMC NPC.”

“Oh, he’s a stooge for the military industrial complex.”

“Gross, he thinks Chinese people are subhuman.”

“Nice, he’s got the correct opinion about ______.”

And so on.

What I try not to do is to allow this to subtract from my enjoyment of the author’s work. The reason is because I’m skeptical of the existence of something called contra-causal free will, which means that I think that human choice is necessarily bounded by the laws of physics and the configuration of atoms in your brain.

To make it simple—the human being is not, in the fundamental sense, capable of something truly sui generis (an act of pure creation). Rather, the human being (and the artist), is a conduit for antecedent forces stretching all the way back to the origin of the universe.

If a human being is a conduit, then so too is the artist.

The artist’s work is thus a kind of remix, the randomized mixing of history, politics, culture, family, personal experiences, genetic talent, and so on. And in many cases, the artist’s work yields beauty—even in spite of their own moral or characterological flaws. To create something is to reach for something, and in so doing, to exceed the limitations of your own brokenness and ugliness.

To an extent that’s perhaps a latently Christian way of looking at thing, and I am no doubt the osmotic recipient of the latent Christendom that permeates our culture even to this day (i.e., in the form of secular progressive morality/wokeness).

But I think, nonetheless, that this is the essentially correct way of viewing art, because the alternatives rapidly collapse into homogeneity and incoherence.

Moral purity vs. aesthetic diversity: what matters more?

The first piece I wrote for DECENTRALIZED FICTION was about the idea of literary culture as a kind of secular “purity culture.”

The basic thesis of this piece is that the homogeneity of contemporary MFA-literary culture is a function of group morality norms in elite progressive circles (and literary fiction is increasingly confined to a cognitively elite subset of wordcels).

Essential to this culture is a type of aesthetic purity spiral wherein increasingly tenuous associations (i.e. several degrees of separation) with fascist figures become the “threshold” beyond which a novelist’s work becomes irrevocably morally corrupted.

The end result is our current crop of contemporary literary fiction, which is afflicted with a terrible sameness. So much of the time, “it’s all so tiresome”—it’s the same type of person, with the same type of ideas, writing about the same type of things. The joie d’vivre any notion of an edge: gone, obliterated.

The underlying assumption behind this kind of perspective is something like the Just World Fallacy, but for fiction: novels should mirror the world back to us as we think it ought to be, and deploy a didactic lesson (in this case, a progressive one). Deviations from this strict standard are categorized as problematic because of their ability to shift social norms into harmful territory.

The argument goes like this:

If we allow XYZ behavior or attitude to be depicted positively in a narrative form, this will percolate through the culture and shift people’s actual beliefs (memetic shift).

By shifting people’s actual beliefs, they will change their behaviour and enact actual, real-world harm (behavioral shift).

On the face of it, there’s nothing obviously wrong with with his argument. It’s just that I reject the underlying assumption: the notion that the purpose of fiction is to reify group moral norms.

I disagree. I think the primary purpose of literary fiction is simply to present the aesthetic experience of human consciousness. Note that I framed that as the primary purpose. That is not to say that no moral considerations whatsoever should figure into the work, but that morality need not be its overriding purpose, and that we need not trade them off against one another so strictly.

Wretched, broken, flawed characters—and by necessity, their morally warped worldviews—are intrinsically worthy of narrative representation for aesthetic reasons alone. That is the value of transgression; I am, indeed, arguing that it is fundamental.

With that out of the way, let’s talk about pussy.

The aesthetic value of wretchedness: The case of Delicious Tacos and uncomfortably honest autofiction

When I read a novel, I’m looking for a story about a particular character—not a sermon. This doesn’t mean that I won’t have a moral reaction to a character, but rather, that I am not reading a story in order to reify my own moral worldview. In my view, this is an impoverished way of looking at art.

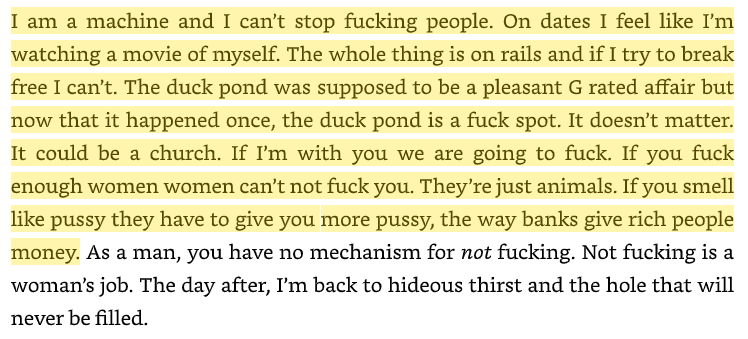

A lot has been said about The Pussy by the pseudonymous ‘Delicious Tacos,’ so I won’t delve into a full-fledged book review here. It will suffice to say that, as far as short story collections go, it’s about a middle-aged sex addict trapped within the matrix of his own self-loathing and compulsive pleasure-seeking behavior. It’s Houellebecqian in that it’s about human wretchedness and male wretchedness in particular. Originating from posts on his pseudonymous blog, it’s presented as thinly veiled autofiction about a deeply troubled man. It’s an unyielding account of pathological horniness so deeply intertwined with black-hole-level despair that one wonders how horny this man had to be in order to go his entire without killing himself.

And although this “shtick” has by now become a meme that other writers have templated and copied, it’s still very, very good.

Indeed, his sometimes-title of “American Houellebecq” is well earned.

And the reason, in my view, that it is so good, is because this character, as he is presented, is so deeply, thoroughly vile.

But it is in this vileness, it is in the particulate mud of this granular psychological detail, that we receive an honest account of a certain-type-of-guy that would otherwise be impossible to access. It’s as if his brain was scanned and frozen in alphabetical amber.

There’s a number of passages I could excerpt here, which, if I was a journalist, I would use as incontrovertible evidence that the author is a sick, awful person.

Instead, I will present just one, and I will offer an aesthetic—not a moral—form of commentary.

“The only crack in her Oriental inscrutability.”

It’s a line that would get you kicked out of any good MFA program, summarily executed in a circular firing squad.

It is also, very obviously, a momentary slice of a stream-of-consciousness that is real beyond measure. It’s a sentence that reveals more about how Asians are viewed in America than a hundred Netflix specials that have been force-fed into your eye sockets. It illuminates man’s propensity for racial dehumanization and the persistent memory of a colonial hierarchy that was erected by his forebears and which remains perpetuated by a ring of Anglo-American imperial outposts today.1 It describes a consensual financial transaction but it’s spiritually descended from My Lai and the Phoenix Program and the government of the United States of America.2 And it’s distilled in a single, off-hand joke about the valuation of human life and essential perspective of a certain-type-of-guy’s essential orientation to the Asian woman: as a piece of meat.

Am I insane?

Why am I arguing that this is aesthetically valuable?

Why would I, as an Asian person, still benefit from reading this?

The aesthetic value of wretchedness

I’ll start with a caveat.

I think it’s extremely clear that literary fiction isn’t as memetically “damaging” as visual media. For reasons of scope (smaller audience) and memetic penetration (textual narrative is less potent than visual narrative, probably by an order of magnitude or more). I’ve never in my life been “offended” by a novel, but certain films and television shows have made me fairly angry (e.g. Sacha Baron Cohen’s grotesque racial caricatures of Central Asians).3 In short, literary fiction simply doesn’t “trigger” me in any substantive way.

Further, the literary presentation of wretchedness is not didactic (definitionally, wretchedness cannot be presented as celebratory). Delicious Tacos is not, in any meaningful sense, arguing that he is a moral exemplar. The autofictionalized protagonist of his short story collection can be criticized for many things, but he cannot be criticized for a lack of honesty. He does have a suite of rationalizations, but they are not constructed as exculpatory. He understands the depth of his own spiral.

Of course, that’s not a positive articulation of why I like to read Houellebecqian literature about bad people.

Here’s what it boils down to: prose-based narratives centered on the interiority of awful people are intrinsically valuable for aesthetic and revelatory reasons. They are aesthetically compelling and they are revelatory for the same essential reason: they present a truth about the world. And in literature, the truth is interesting.

For me, that’s a good enough reason to get something out of a story.

Houellebecq himself frequently mentions that, in his view, novels don’t change the world. This is certainly true now as barely anyone reads novels. Check out this exchange from an interview when “Submission” (2015) came out:

Houellebecq: But essays are what change the world.

Bourmeau: Not novels?

Houellebecq: Of course not. Though I suspect this book by Zemmour is really too long. I think Marx’s Capital is too long. It’s actually the Communist Manifesto that got read and changed the world. Rousseau changed the world, he sometimes knew how to go straight to the point. It’s simple, if you want to change the world, you have to say, Here’s how the world is and here’s what must be done. You can’t lose yourself in novelistic considerations. That’s ineffectual.

https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2015/01/02/scare-tactics-michel-houellebecq-on-his-new-book/

Great read.

I agree with a lot of what you've said here, especially when it comes to the role of the artist as a conduit for his influences. It reminds me a lot of how T.S viewed artists in his essay, Tradition and Individual Talent. Have you read it?

For me, of great interest is the artist's awareness of his place in the narratives of history, and the ability to understand why the presence of the past is so significant to him. And, following Elliot's advice, the artist must self-sacrifice to these influences of the past, thus the artist becomes merely a medium for the art he wishes to indulge. I'm going further than Elliot here, but I may or may not unironically believe the artist may become possessed by a muse if he's humble enough.

Regardless if you agree with Elliot or not, I think we can agree that the focus on individual talent and expression from the modern Uni art scene is one of the cringiest things out there. Both in theory and ever more so in practice. Cause 'in practice' you're only ever allowed to be expressive and original as long as your ideas align with the morality of progressive aesthetics.

To me, art is fundamentally an exercise in empathy: Good fiction makes you enter the imagination of another human, you don't have to like him or agree with him, but you learn to be next to him and to understand him.

However, social media complicates this. I've had the misfortune of reading Delicious Taco's social media before touching any of his fiction. And yeah, based on his online personality, I can't say I'd like to read any of his work (Then again, the stuff you've shared here looks promising!) I think this is a modern problem. Because of the internet, it's harder to separate the art from the artist, even if it's the right thing to do. Never before have authors been so exposed to the judging eyes of the audience. The days when readers had to carefully analyze your work to get an image of who you are or wait till the biography comes out, are gone.

The aspiring artist can choose to remain anonymous online, but current publishing trends compel you to have an active and viral social media presence to have more chances of being published.