2024 Year in Review - Decentralized Fiction, INCEL, and the /newwave/

Failure and success at the outer margins of the wordcel literary universe (WLU)

It’s a well-worn trope that the modern writer is well acquainted with failure.

What’s less discussed is that this causal relationship actually runs both ways.

The standard line is that writers are conditioned to accept failure because of the practical necessity of rejection on the path toward publishing.

The more interesting explanation—which is not incompatible with the first one—is that people who are failures are more likely to become writers.

The reason for the former is the structure of the traditional publishing process. The reason for the latter is because the payoff matrix for literary fiction has imploded over the past 20-odd years, with few exceptions: any modern creative is necessarily playing a tournament-style competition against other artists in the attention economy, but the payouts for novelists are well below those in cinematic narrative (or even video game narratives).1

Intelligent people are not unlike the rest of us. They tend to be attracted to incentives. For both men and women, the litcel to celebrity pipeline has dried up almost completely—now only the alphabetical autists remain.

Note that this is a form of adverse selection.

See, only when you’ve washed out of every other possible domain of success in life can you truly become a writer of literary fiction.2

It’s possible that this is partly a good thing—maybe it’s ultimately better for the form that only literary purists remain in the game. Maybe it becomes something like classical music.3

For the cohort of young novelists who fall in the camp of delusional optimism, self-imposed expectations might best be described as a form of self-harm: it’s like betting your self-esteem on a lottery ticket. In the case of literary fiction—the only wordcel arena that I care about—said lottery ticket takes the shape of a novel.

Based on my personal experience, I would advise against needlessly constructing fake problems. Indeed, the solution to the problem of literary ambition is actually very simple.

At the highest level of abstraction, a human being is an agent, and agents are defined by goal-seeking behavior. Goals are essentially just unsolved problems. Therefore, there are two ways to make a problem disappear: you can solve the problem, or you can literally just decide that it’s not a problem.4

It’s remarkable how tight the tautology of the latter is: if you have a problem but you decide not to care about it, then it disappears.5

Years ago, when my traditional life path wasn’t working out, I used to cope by internally referencing my novel as a sort of pillar of meaning. In the process, the various problems of my life dissolved into the background, replaced by the relative importance of the only thing I really cared about: my book.

But contained within this idea of a novel was something else.

I dreamed of “making it” on the internet.

In short, I dreamed of an outcome—not a process.

No matter how fucked up my regular life situation had become, I always had a manuscript to return to, and with it, some probability of success. Tangible progress was continuously being made from draft to draft and scene to scene. At times, it was hard to maintain motivation over the long haul, but I also felt continually satisfied by the linear improvement of the manuscript as I worked on it over the years. Beyond that intrinsic motivation alone, I also took great satisfaction in imagining its eventual reception.

I wanted a form of breakout literary victory. I wanted to become, on some level, to become a name.

Thus, writing was my ambition-release valve, a way to redirect the failures of my conventional life into the cope of an artistic work.

I became so used to the ongoing process of moving toward finishing my book that when I published it—without any platform whatsoever—it was more or less guaranteed to end in profound disappointment.

By any conventional standard, I failed to achieve the outlier sales figures that I’d hoped for as a (much) younger man striving toward a Houellebecqian future.

As much as I thought I felt motivated by the intrinsic reward of writing, I came to realize that a huge component of its meaning was driven by the desire for recognition from others.

Of course, this was partly a form of delusion.

Every young novelist who starts out seeking recognition is deluded on some fundamental level: they are effectively spending years of their life writing a book that almost no one will read. There is no utility function that can really justify this in spreadsheet or utilitarian terms.

The paradox of artistic ambition: it’s vain and narcissistic, it’s notice-me-senpai energy (however senpai might be construed); simultaneously, it really is something that you do for your soul. It’s a fundamentally spiritual exercise.

There are many niche works which are truly exceptional but have failed to find the audience they deserve—I would know, since I’ve already read several of them just this past year.

I view every orphaned novel as a tragedy. The world, as we all know, is full of them.

I made an idol out of literary success—and, so long as I hadn’t published my debut novel—I’d succeeded in one thing only.

I created an unfalsifiable hypothesis about my own value as an artist and human being that wouldn’t make contact with reality anytime soon.

For years, it was an impenetrable coping mechanism for the slow-motion car-crash of sequential failures that were constantly deforming the neatly-laid-out path of my life.

Then came the market.

ah fuck lol

At one point, I genuinely thought that my self-published Amazon book would sell many tens of thousands of copies—even hundreds of thousands.

One can laugh at the absurdity of these self-imposed expectations, but I genuinely believed this. Hope and delusion exist on a continuous gradient with realistic appraisal on one end of the spectrum and florid psychosis on the other.

For me, naivete was a convenient excuse: I never had any real contact with the publishing industry whatsoever. So, from the perspective of hindsight, I can partly argue that this was mostly borne of a lack of experience and an inability to sufficiently calibrate my expectations to the reality of power laws in the attention economy.

A second, more truthful explanation: I really thought I’d written the next Fight Club-tier work about modern masculinity. I thought I had lightning in a bottle.6

With the benefit of experience, I’d speculate that delusional overconfidence is built-in to the psychology of asymmetric goal-seeking behavior.

I am pathologically addicted to big bets, even when they always seem to fail completely. I have done this over and over in my life, and I’m not sure I could stop even if I wanted to. I’ll admit that it at least makes my life more interesting.

On and off, my self-published book—essentially one of millions of print-on-demand KDP products—consumed roughly a decade of my life.7 Typing that sentence feels absurd and embarrassing.

Sure—I was doing other things (waging full-time), but on some level, I really did burn a decade of time for this, and naturally, releasing it led to a very simple question.

Was it worth it?

I turned to the market to answer this question.

What did the market say?

Well—famously, it’s been said that the market is never wrong. The level of demand is the level of demand. Surely this is at least partly correlated to a book’s value, is it not? How deep is a writer’s reservoir of delusion?

It’s not infinite, I can tell you that.

I’m not one for publishing online confessionals, but I’m also a fan of being up front when it might be useful for other writers. I’d be lying if I didn’t say that I looked at my sales figures with some level of despair in those first few months.

Those pre-prepared wordcel tropes about literary quality and consumer attention being intrinsically decoupled just weren’t doing it for me.

I really, truly, sincerely thought my stuff was going to take off in some big way.

Writers sometimes cope by pointing out Moby Dick was an obscure work until after its author’s death—in premodern times, they could manage the psychology of failure by dreaming of being rediscovered as a literary savant years after their death. They extrapolated their own literary culture into an indefinite, linear, future of literacy stasis where modes of artistic consumption didn’t change.

As is now obvious to everyone, we are accelerating into global dopamine slavery. These kinds of narrative salves are no longer tenable.

Enter enlightenment

Artistic demoralization is a subset of general demoralization. That is to say: it’s a gradual thing. Your yearning gets flaked off with a chisel in little pieces until you quit.

It’s also, I’ve discovered, completely unnecessary.

One day, I decided to stop feeling disappointed. The incredibly simple solution for my suffering was merely to lower my expectations.

Instead of being an idiot and comparing myself to writers who’d sold many thousands (or even millions) of copies, I chose to compare myself to other indie writers who’d emerged from the same micro-niche.

Suddenly, I was back in the game. I was a live player.

Mentally, I gave up on the idea of becoming the next Houellebecq (or even the next Delicious Tacos). I just kept on promoting my blog and I had fun writing it.8 Likes and comments on long form writing juice your soul in a way that Twitter simply can’t. It’s inherently more motivating.

And that—almost magically so—is when things went my way.

Turning point: New York City

The main inflection point came when Ross Barkan put out a combination review of my novel, INCEL, and Adem Luz Rienspect’s debut, Mixtape Hyperborea, in the Mars Review of Books (MROB, for short).

It’s hard to articulate how big of a deal this was to a zero-name outsider like me.

Years ago, I’d read Christian Lorentzen’s review of Logo Daedalus’ Selfie, Suicide in the same magazine, and dreamed of being similarly covered. What MROB was doing with literary magazines was emphatically something I wanted to be a part of. While I don’t live anywhere near New York (or even CONUS), I like to visit it from time to time, and the network effects from its dense concentration of wordcels isn’t of imaginary importance.

The strongest scenes require social fission borne of geographic proximity. The simple reality of literary fiction is that it is now essentially a form of high culture, and cultural value is imprinted by way of social proof which is connected to social status.

Even in our world of parallel literary institutions located firmly outside the sphere of traditional publishing, becoming established essentially boils down to being vetted by someone else who’s got a proven track record.

By any objective metric, Barkan is a highly successful, 99.9th percentile journalist and novelist who is poised to release a novel that has a very good chance of pushing him to an even higher tier of critical and commercial success in 2025.9

When you’re coming from nothing—no credentials, no MFA, no network, no platform—coverage like that instantly becomes a substantive personal victory. I’m very grateful to be in the conversation amongst this community of writers because I believe in the caliber of their work very strongly.

Sufficed to say, this turning point set the tone for the rest of the year, and gave me motivation to keep on blogging. Spiritually, I’d more or less given up by that point.

As the year progressed, it became obvious that Substack was the primary driver of my book sales. When I published a good piece that got a fair amount of traction, I’d net a couple book sales almost immediately. The correlation was sufficiently obvious so as to be clearly causative.

To expand on that point, I am now completely sold on this platform as an outsider artist: without it, I would’ve probably sold 90% fewer books. That may sound like an exaggeration, but because my Welcome E-mail includes an invitation to purchase my novel, each new subscriber has some chance of converting to a sale.

The network effects on this platform are really that strong: I’ve been fortunate enough to garner numerous additional reviews on the platform from other writers like Hyun Woo Kim, who wrote a very unique take on the book.10

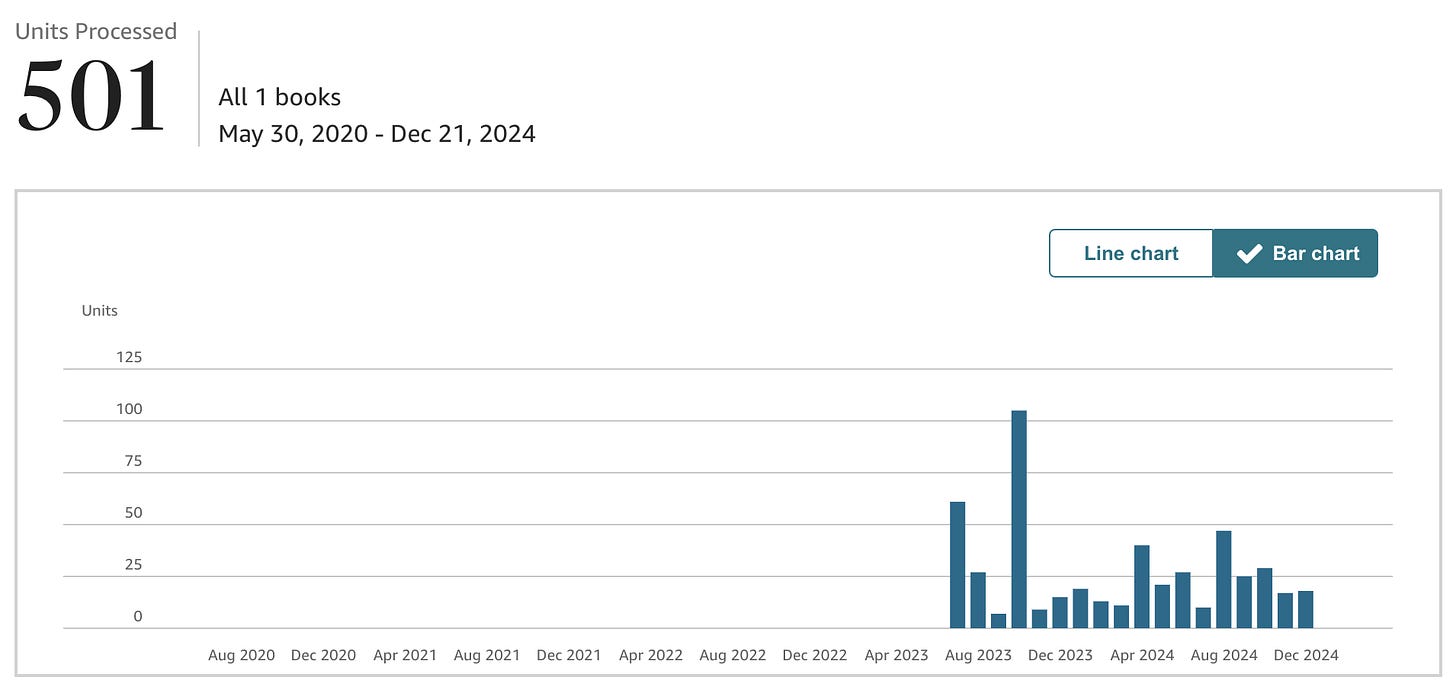

Now, for some objective metrics.

Here’s a snapshot of my book sales at the time of writing:

By the standards of a Chuck Palahniuk, these figures are a laughable failure. An absolute pittance—take your ball and go home.

Do not pass go; do not collect $200.

By the standards of some niche guy on the internet without an agent or a publisher, they’re a comfortable success.

Since I have the freedom to choose, mentally, who is to be my point of comparison, I’m choosing to go with the latter.

It really is that simple, folks!

Optically, I know that all of this is could’ve easily been predicted beforehand, but I have a recurring problem with obvious truths in life.

For some reason or another, I always have to learn them the hard way.

The real success was the friends we made along the way

For the longest time, I didn’t understand the value of relationships between writers.

My attitude was—I already have an editor. I’m paying this person with my wage-dollars to critique my work, and they’re going to care a lot more than other writers because it’s their job to do so.

Why “network”?

“Networking” implies Linkedin which implies complete soul-death.

I didn’t get into the alphabetical single-player game so that I could network, for God’s sake.

I said to myself—“Han, is networking going to make your manuscript better? If not, then why do it at all?”

Even if it’s just for marketing, what’s the ROI on networking when you’re disembodied and floating in the digital ether? It’s making connections on hard-mode.

When I put out my book, my initial set of cold e-mails largely went nowhere—to the extent that I got any attention at all, it was because of an extremely lucky chain of events that came out of advertising my novel on the /lit/ board.

It took me awhile to understand, but I think I get it now.

The first part is the pragmatic value. Reviews and relationships function as a kind of credible, off-platform verification for the caliber of any given work. Without a review from an established entity or writer, a novel feels untethered to a serious critical response. A serious review anchors a novel in a moment of historical time. A book alone isn’t an entry in the ledger. A book plus its reviews is the entry in the ledger.

The second part is the value of community.

What I failed to understand in my v1 form as a literary autist toiling in absolute obscurity was that writing is an inherently social activity because it’s the transfer of your consciousness into the mind of a recipient reader.

Books exist to be read, as the late Jake Seliger would say (RIP).

Intuitively, I have a Pavlovian hate for the word community because I always associated that with crypto scams or other meaningless corporate-speak. But—precisely because the financial stakes for novelists like me are so incredibly, comically low—community is actually the most rewarding part of this entire process.

Of all the things I did this year, the most fun I had in 2024 was appearing on podcasts.

It was the year where the idea of wordcel community really clicked for me.

(For context, I wrote about why I think literary podcasts are important here.)

On March 18, 2024, I had a great conversation with LEAFBOX about my novel and the broader subject of incels. This was my first podcast interview and an incredibly exciting experience. On August 4, 2024, I had a really interesting craft-heavy discussion with Jack BC of Book Club from Hell (whose novel I also reviewed the same year).

One of the most insightful commentators I’ve met in this space was Gabriel K. Sinclair, who I had the pleasure of chatting with on two occasions - August 27, 2024 & September 8, 2024 (note: the audio from the second interview is better). Sinclair is one of the most shockingly insightful critics I’ve encountered, doubly so because of his relative youth and learnedness.

Lastly, on October 17, 2024, I finally synced with Matt Pegas & Dan Baltic, where we had a great discussion about androgenic fiction and the /newwave/.

A rhetorical question: what’s the relationship between a pseudanon and writers he’s never met in real life?

Is it friendship? A more loosely defined camaraderie? A professional colleague? Or some tenuous hybrid alloyed with all three of these elements?

I don’t exactly know the answer to this question, but it’s undoubtedly fuel for the scene, the commentariat, and its growing cohort of artists.

Most importantly, it’s fun.

Fun things continue; they are self-perpetuating, infused with vitality, and vitality is what endures.

/newwave/ shillfest

This is a theory-heavy literary blog, and I’m addicted to hyperstition.

I am going to keep trying to hyperstition my way to victory for the same reason I keep putting my wages into worthless shitcoins: because it’s fun, and one of these days, it might actually pay off.

When I first put my piece on /newwave/ fiction out, I was highly surprised by the response the article provoked since my theory-heavy stuff doesn’t tend to get a lot of traction relative to more scene-focused analyses.11

Clearly, there something about the response that hints about where the Wordcel Literary Universe is going. In the spirit of fair-minded discourse, David Herod of Tooky's Mag weighed in with some great arguments that he later expanded on during a great interview with Jack BC on the Book Club from Hell. Cairo Smith added some very incisive commentary on the Futurist Letters that also rightly took off as the discourse coursed among us (coursingly).

I largely agree with David that a purely negative framing of a literary movement is insufficient to activate the level of zeal required for true aesthetic progress. A positive vision is required, and that’s something the /newwave/ needs if it’s ever going to take off beyond three or so people on stuck (lmao).

(As an aside, maybe that’s what was ultimately missing from Dimes Square, and why it petered out.12 It never felt like it was about something.)

I have more to say about literary scenes and movements down the line—to what extent do they require social status in real-world social networks and locales? Can you build it in a completely disembodied, online-only manner? Or do you need to host IRL events?

Only time will answer these questions, but I’m increasingly excited by the metaphor of the wave itself. The concept of turbulence, chaos, and overlapping contradictions are the hallmarks of vitality: a novel isn’t a logic puzzle or a political treatise or an instruction manual or a moral parable—it resists instrumentalization by its very nature; a product of human agency that invariably takes on some of its own.

The idea of a RETVRN to a truly dialectical form of literary fiction excites me because artists need the freedom to violate ideological world-models and the freedom to contradict themselves at every opportunity.

Now, whether or not this mutates into the next literary movement remains to be seen, but what is clear is that this level of untapped creative yearning is a vacuum that will be filled one way or another.

So—dear reader, if you’ve made it this far, I have only one thing to say:

I’m grateful for each and every one of you, and for all the friends I’ve made along the way. I’m grateful for anyone who’s ever read this blog and for anyone who’s ever read my fiction and found it worthwhile.

It’s been an absolute privilege.

Here’s to a great 2025, and to the good things that are coming our way.!

Which, incidentally, also has terrible odds of success.

I’m exaggerating, of course, but I’m directionally correct, lol.

(The problem here is that rich people don’t value sitting at readings the same way they value sitting at the opera).

I can confirm that Buddhism is just ONE WEIRD TRICK, after all (Monotheisms HATE him!!!).

This wisdom came to me in the form of a Pepe meme screenshotted from 4chan.

Hell, maybe I did! Maybe if I’d released it in 2016 something magical would’ve happened, but there’s little point in worrying about counterfactuals. It took a long time because I wanted it to be written to a certain standard; it was done when it was done.

I’m a compulsive perfectionist and a slow writer. I hope to be faster with my next one.

Most of these posts are written in about 2 hours on weekends, i.e., whenever I feel like it.

The novel is called Glass Century and I will do a piece on it when it comes out.

See his review here.

Thank you to Gabriel K. Sinclair for letting me steal the term and Postliberal Book Reviews for the /newwave/, /lit/-inspired forward-slash notation.

In fairness, the definitive Dimes Square book, Gasda’s novel, has not yet been published.

Thanks for sharing details of your journey thus far, and for sharing current metrics. “My Welcome E-mail includes an invitation to purchase my novel, each new subscriber has some chance of converting to a sale.” …what other methods have helped create sales that are within your control?

I thought I could write a novel in a year, and I did. At least Im not so delusional that I believed it was good enough to put out into the world.