Sometimes I wish I had it in me

Poverty, suffering, and fiction-writing as a character-building exercise

It used to be that I’d work my full-time job and I’d come home after the gym and instead of doing more work, or studying, or any of the other things that would’ve been objectively beneficial for the advancement of my career, I’d sit at my computer and loop some good music and work on my novel late into the evening.

And I did this for a long time.

I remember, as a consequence of this habit, feeling constantly tired, constantly burnt out, and always feeling that I lacked sufficient time for my art. My job felt like an obstacle to the thing that I wanted to be doing and my entire life felt like a series of obstacles preventing me from doing what I wanted to do—to be a writer. I felt like the constraint of nights and weekends was a set of chains holding me back from greatness.

(I was, after all, going to become the next Chuck Palahniuk, the next Bret Easton Ellis).

My experience of being a (primarily) self-taught writer was that my progress was decidedly linear over time. Successive manuscripts were hierarchically positioned above one another, and my rate of improvement continued year-over-year until I completed my first novel in 2023, some eleven-and-a-half years after I started.

Time has never not been a constraint for my personal development as an artist.

In 2014, I took a year off and lived in Southeast Asia for a couple months. I basically did nothing but work on my novel, lift weights, and walk around a lot. In addition to making some great gains, I finished my first manuscript of INCEL, which received positive feedback from my friends that sustained me for a couple more years.

It was the kind of thing I could do when I was young and it felt incredibly liberatory at the time. I’d been on NPC-rails for most of my life up until that point, and artistic freedom felt better than anything else I’d tasted before.

But I was living on debt. The clock was always going to run out.

I sometimes see this phase of my life as a road-not-taken and think about what might’ve happened had I committed myself to art full-time.

I didn’t have it in me.

Not even close.

It’s tempting here to do that Asian-American whining thing—in my culture, it’s really important to have a job—yeah, no shit, in every culture it’s important to have a fucking job!

When I really think about that moment in my life, my ultimate path came down to three overlapping factors:

I didn’t want to give up a certain minimum level of consumption-oriented, middle-class lifestyle.

This lifestyle required me to, at minimum, work a normal job and be a normie.

I felt like I couldn’t drop below a certain “status floor” in life, which similarly required having a job.

In economics, there’s a concept of something called the “revealed preference”—it’s the way your actions reveal your true priorities.

Roughly 2-3 years ago I read Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian at the recommendation of /lit/. It’s now positioned as something of a “meme” book, but I think the denigration of this novel is largely driven by contrarian status-signaling.

It’s astonishingly well-written, neo-Biblical, magisterial prose.1

What I find equally interesting is how it compares to one of his much earlier works, Child of God.

The comparison between Blood Meridian and Child of God is stark. The sentence-level craft and complexity of the former far exceeds the latter, although McCarthy’s signature is consistent throughout.

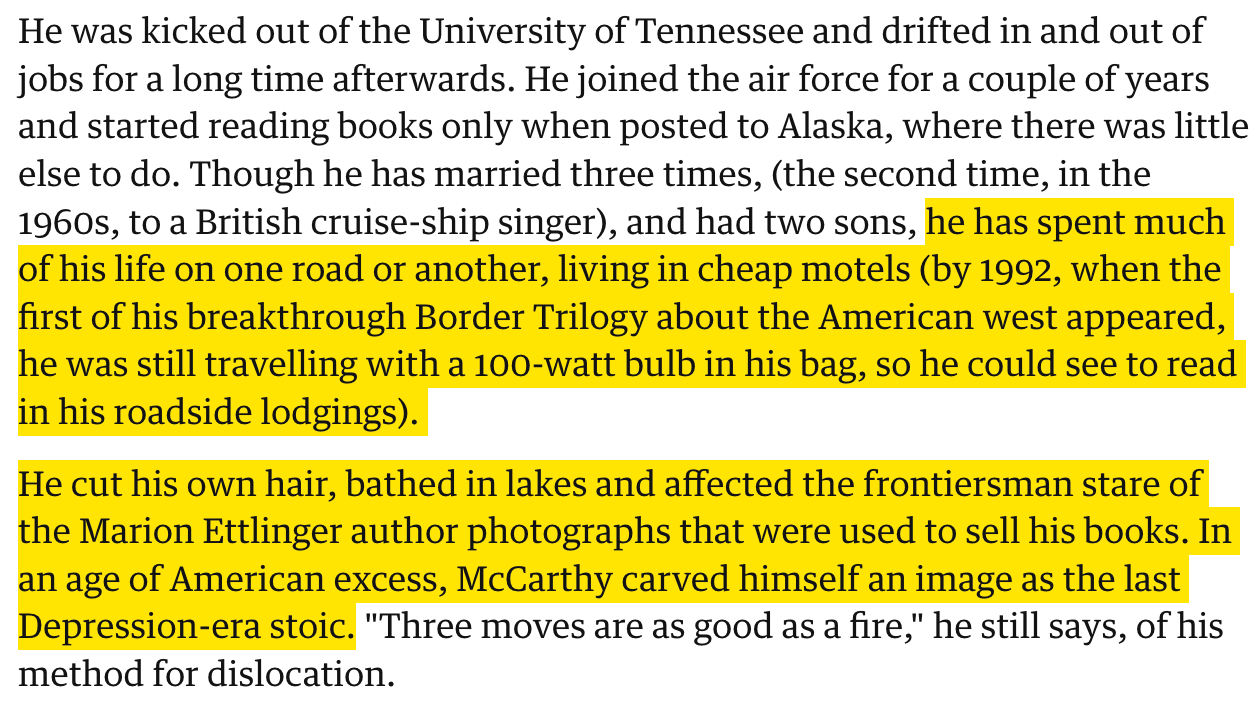

See, the thing about McCarthy—one reason he’s so respected as a writer—is that he deserved his success.

And the reason he deserved it is not just because he was willing to put the work in, but because he was willing to put the suffering in.

I remember always being annoyed when people would tell me that they were “spiritual, but not religious.”

For me, this was always the signal of an unserious person.

You might as well say “I’m willing to believe anything so long as I don’t have to pay a price for it.”

The strength of your belief is measured in what it cost you.

The same, I think, is true of art.

Yes, McCarthy eventually made it and found his deserved success, but that does not erase the years of living in cheap motels and being so poor that you need to read books with a light bulb stored in your bag.

What right, then, do I have to complain?

I chose what I chose, did I not?

One reason I think that literary fiction is dying is because the rewards of literary greatness are so paltry relative to other narrative or creative media (film in particular). I’m not going to add to the chorus of people bemoaning the sloppification of mass culture but I am going to note that human beings—including artists—follow incentives.

We are, plausibly, caught in a kind of doom-loop whereby individuals who could become great writers can no longer sustain the multi-decade marathon of practice required to achieve said greatness.

This deficit in contemporary literary greatness furthers the shrinking of the pool of readers, minimizing the rewards even moreso.

I mourn this process as much as anyone, but I can’t help but draw from my own experience in understanding why.

The failure-mode of the aging man is his attempt to recapitulate something that belongs only to youth, without realizing that this earlier phase has definitively passed him by.

In 2023, I took another break from corpo-world and had a year-long period where I was free to write as much as I wanted, more or less. I worked enough to sustain myself on a part-time basis, and no more.

But it didn’t feel like the first time.

It felt notably worse than my first sabbatical in 2014—in fact, it felt bad, because taking a year off has a very different feeling when you’re a middle-aged man versus a young one. And I felt a kind of despair about my future that was so overpowering that I had to promptly return to normie-world so that I could once again afford to eat food at restaurants and buy new clothes without feeling guilty about it or doing arithmetic calculations in my head.

Sometimes I wish I had it in me.

Sometimes I wish I could really walk away from everything and just give it all to art.

But I’m not that person—I am a lesser man, perhaps an inferior man—and that’s okay.

Read Aaron Gwyn’s excellent Substack on this if you want to study the book more.

Great piece. Funny how there's a Romantic movement on Substack when nothing is less Romantic than Substack. Imagine: "Cormac McCarthy struggled for years at magazine launch parties, getting rejected by It Girls like Madeline Cash until his newsletter, Grey Matters, was ranked #3 in literature."

Nice post, ARX, but I don't quite agree with your characterizations here. One can suffer plenty and still work a job; furthermore, the time compression involved in working a real job often forces brevity and economy in writing - no procrastination, one becomes better with one's time. For example, one relative of mine has responsibilities piled to the sky, and throwing another one on the pile is no big deal; another relative has almost no responsibilities, and getting this person to do the simplest thing is like climbing Mount Everest. I'll quote Librarian of Celaeno here:

“It is also important to bear in mind as well that Boccaccio, a writer of the highest caliber, had a day job. Like the Gen-Xers to come, he sold out and went into working world, taking up the family mantle of civic responsibility. He went on important missions for Florence and performed a number of government jobs, including welcoming Petrarch to the city, beginning a great and influential friendship. But he was never fully free to pursue his art, a fact true of nearly every artist then and up to the present. Consider that greats like Brunelleschi and Michelangelo were businessmen working on commissions; their time spent managing staff and studios must have far outweighed their time with brush and chisel. Even profoundly prolific writers like C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien were employed full-time as professors and had all the demands of family life (weirdly in Lewis’s case) as well. Let this be a lesson to those of us who would be artists if we had more time; we always have time to do the things that are important to us. The habits of industry and discipline mean as much as imagination and creativity.” From here: https://librarianofcelaeno.substack.com/p/the-retvrn-of-giovanni-boccaccio

Regarding the nature of suffering itself, yes, one can tell a writer or speaker who's suffered versus one who hasn't, and the difference is stark. I attended a talk last night where the speaker said all the right things, but said it in a smooth and confident way (like a Stephen Colbert) that betrayed a lack of suffering - and for that reason I didn't like the guy on first impression, and felt somatically a desire to stay away from discussion from him after.