Self-licking ice-cream cones and the securitization of the young American male

or, why I cut my novel Afterword

One of the iron rules of bureaucracy is that once a bureaucratic entity comes into existence, it will seek to perpetuate itself and grow indefinitely. On first principles, this an obvious conclusion: just like you and me, bureaucrats like being able to pay their bills and to feel that their work is important and purposeful, just like you and me, they like to increase their power level.

More generally, one way to model a nation-state is as a power-seeking entity—a collective intelligence that is trying to grow (not necessarily maliciously), and extend its lebensraum over physical and economic space until some kind of limit is reached.

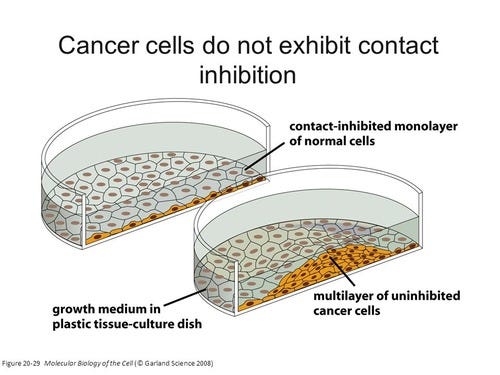

In nature, certain types of cells will stop growing once they reach a mechanical limit. This is to prevent the entire population of cells from reaching a growth level that is unsustainable: this biological boundary function is called contact-inhibition.

Now, let’s ask ourselves a question: which of these two categories best represents the Global American Empire?

Does it attempt to constrain its growth at its line of contact with other WMD-backed powers?

Or does it keep trying to grow into their space?

My goal here is not to persuade you that Putin’s invasion of Ukraine was in any way morally justified. This conflict has needlessly killed hundreds of thousands of people and is a moral horror. I take the conventional view here for granted.

But I have to ask—what exactly is this thinking behind stuff like this?

As much as I’m a fan of postapocalyptic cinema and narratives, I don’t have any desire to live under a scenario like that.

If you were to take a nominal view of the US foreign policy right now, it seems to be obviously incoherent. On the one hand, we’re arming our proxy in Ukraine with long-range missiles, which recently struck a nuclear early warning system in mainland Russia—an insane provocation by any standard. On the other hand, we have indeed taken some steps to limit open conflict and escalation into a nuclear exchange—at the very least, by not yet entering into an open conflict with the Russians.

This seems like an obvious contradiction. What exactly is the fucking policy here?

The policy, my friends, is that there is policy. The incoherence that we are all plainly witness to is the computational output of a bureaucratic institution that has defaulted to the zombie-like behavior of its own collective intelligenc as an institution.

The contradiction can be resolved as follows: the collective intelligence of an institution—say, the American empire—can be much stupider than any one actor within the system (and that is even accounting for the fact that Biden’s National Security Council is basically comprised of malicious Mackinsey-consultant-tier idiots).

Ostensibly, the United States view China as the biggest threat to its hegemony (partly, this is why the US built out the three-island-chain ‘containment system’ many decades ago, a constellation of military bases which have been perpetually expanding since the ‘Pivot to Asia’ under Obama in 2011).

Thus, the stupidity of de-facto creating a Russian-Chinese alliance and removing the threat of a wartime naval blockade against the PRC mainland is a geostrategic own-goal that doesn’t even make sense under the internal rubric of American imperialism.

Again: what exactly is the strategy here?

What events are telling you is that the body is moving without a head. There is no grand strategy at play and no one is truly at the wheel. This enormous imperial machine is acting instinctively, unable to think at a level higher than a single local region or more than a single move ahead, a bureaucratic zombie executing only the simplest possible algorithm: growth at all costs, even if the risks are existential for the entire species.

The most interesting rhetorical critique of American foreign policy I have seen comes from Curtis Yarvin, a right-wing political theorist who pejoratively models it a “self-licking ice cream cone.”

The argument goes like this: whether by way of the CIA, the state department, or the Pentagon, the US foments instability in foreign countries at the edge of its imperial border, creates a crisis, and then intervenes to “solve” it with military force in an effort to continue its expansion or justify its own existence.

While previous generations of American statesmen had, on average, a more coherent and effective strategy (at least by the internal standards of imperialism), it increasingly does this in a completely mindless and stupid way that essentially amounts to bureaucratic automatism—like US occupation forces dissolving the Iraqi army after the end of the invasion (of note, the costs of these errors are now accumulating, and the world is becoming more multipolar).

While this framing isn’t of course meant to be a 1:1 mapping of every American military intervention over historical time, I do think that in many ways it’s directionally accurate in some sense.

This model explains a lot, like our apparent policy of seeking simultaneous conflict with every major nuclear Eurasian power at the same time (or, as I like to call it: fighting the entire Eurasian continent at the same time).

In my view, the revealed preference of our foreign policy is unrestricted growth. To borrow another phrase from Curtis Yarvin: it’s “the ideology of a cancer cell.”1

I don’t think it’s useful to demarcate countries into ‘Liberal democracies’ and ‘Authoritarian dictatorships.’ Political systems and de facto freedoms present themselves on a continuum of openness and liberty, not a binary scale.

I think a more useful mental model here is the sliding scale: and on this front, we are very clearly going backwards.

In a truly excellent article written by N.S. Lyons, he argues that all Western liberal democracies have significantly regressed in terms of their actual commitment to the core tenets of Liberalism.

Now—let’s increase the resolution of our analysis and zoom in to the the level of the domestic US.

After 9/11, we saw a dramatic expansion of the domestic security state in the form of the creation of the DHS, increased surveillance on Americans by the NSA, and the militarization of the police.

What is the domestic equivalent of the US foreign policy blob?

It’s our domestic security blob, a collection of bureaucrats who, much like the same foreign policy elite who are constantly creating messes abroad, are in turn creating messes at home (note that the UK and Germany, for example, have become similarly domestically repressive).

After the decline of Islamic terrorism as GWOT wound down and Muslims became successfully assimilated into wokeness and progressive political coalitions, the DHS and FBI simply found themselves with less to do.

So what does a bureaucrat do when the supply of terrorism falls below its bureaucratic demand?

Why, it’s simple!

They create more terrorism, of course!

There’s two ways to do this:

Grooming: the alphabet soup guys can groom or entrap alienated young men in an effort to turn them into terrorists. For a particularly egregious example of this, read this article. Another recent example was those unfortunate fellows in Michigan.

Concept creep: the domestic security apparatus can redefine broad swathes of the young American male population as potential terrorists. Extra points if they’re part of your enemy’s political faction.

And here we return to the same underlying logic of our foreign policy blob: threats are omnipresent and omnidirectional, and state power must inexorably increase at all times in order to combat it.

The collective intelligence of the bureaucratic organism cannot be restrained by any individual actor internal to the system. In the American context, these agencies all seem to converge on growth-above-all as the motivating mindset. As an aside, I do think it’s possible that this is a natural decay-state for human institutions that is in some way analogous to an emergent form of institutional aging and explains (in part) the cyclical rise and fall of powerful companies, countries, and empires.

Even though there are multiple documented cases of incel-motivated terrorism, I think that increased attention on incels as potential terrorists largely falls under the second category—that is to say, while some incels have committed acts of terrorism (most notably, Elliot Rodger), the risk of incel-motivated terrorism is objectively very low relative to their number in the population.

And yet, we see a proliferation of discourse on the topic that seems wildly out of proportion to the actual threat.

I was reminded of the actual statistical risk when I watched this excellent interview with William Costello, a researcher on the subject:

Costello says about 59 people have been killed by incel-related terrorism in human history.

By comparison, about 3 women are killed by an intimate partner in the US alone every single day. By definition, these men are not incels, which means that non-incel men are much more dangerous to women than incels.2

And yet, femicide is much less likely to be a significant part of our cultural discourse or merit concern from the security state. The latter may simply be due to the nature of categorization of crimes in that ‘standard’ crimes like femicide are definitionally not regarded as terrorism, but that still begs the question of why the domestic security apparatus apparently indexes so highly on allocating resources to this statistically-insignificant risk.

At current rates of growth, we’re reaching into the realm of parody. The alphabet soup guys are apparently so bored that they’ve started to surveil gamers:

In fairness, the United States absolutely does have a problem with mass shootings. But I think if we were to take a wide view of this trend, we’d realize that it’s as much a social problem as it is a terrorism problem.

Mass shooters are increasingly less ideologically organized and more and more driven my mental illness or the psychogenically infective mimetic ritual of murder-suicide for its own sake. Their stated justifications are becoming more and more confused and incoherent, more a symptom of psychosis and social contagion than of an Anders-Breivik-style political project or anything that could conceivably be tied to a coherent political outcome. There are simply fewer things that young men truly believe in, and therefore fewer beliefs for them to kill for.

In short, this is why I decided to cut my Afterword from my novel.

In my Afterword, I used a word that I no longer think is the right word—deradicalization.

The fact is, there are millions of incels in the United States and only a miniscule micro-fraction at the absolute margin have engaged in acts of terrorism. Further, my novel is emphatically not a narrative about a guy who is contemplating terrorism in any serious way. While I never expected that my novel would prevent terrorism (a proposition that is absurd on its face), I used the term because I felt like my narrative might attenuate some of the more blackpilled worldviews that are not in any way scientifically or empirically supported by evolutionary psychology.3

The term for this psychic gear-shifting is not deradicalization, nor is it a psychological operation.

It is, simply put, a spiritual thing: a turn away from nihilism.

The danger of having strong convictions as an artist is that you will lean into didacticism too forcefully and in so doing, you risk subtracting from the power of your art. I self-parodied my own natural impulse in this direction through my novel’s chapter about the dangers of ‘hegemonic ethnomasculinity’ as evidenced by the historical disasters of WW1-era European ethnonationalism (which completely destroyed the continent and later imploded all of the European colonial empires), but I also pushed back against this notion that Reddit-style tonal mockery has any positive effect in changing minds and turned the scene into a comedy.

(As an aside, because the moral logic of militarized ethnosupremacist nation-states is largely an axiomatic moral principle, I think it’s often useful to argue against these projects by turning to historical examples of moral consequentalism—just look what this did to Europe! Look at the mass graves in the hospitals of Gaza!)

I no longer believe that sad, alienated young men in America need to be ‘deradicalized’ even in the nominal sense of the term (i.e. as an approach for returning them into the fold of society). I think this word is not useful and should be avoided and needlessly creates antagonistic feelings by securitizing existential malaise as a precursor state for terrorism. The truth is we are living in a late-USSR style social collapse in the US which has completely eviscerated any possibility of meaning for vast swathes of the population, young men included. Some tiny fraction of these people, many of who are dying deaths of despair, spin off into hurting others. But the core trend is not something that is intrinsically applicable within a security-oriented framework.

That modernity has obliterated hope for so many is not a problem that intelligence agencies can solve with guns or surveillance.4 It is a social problem and a crisis of meaning. The answer is not to kick down doors with SWAT teams and police video gamers, for god’s sake.

Below, you can read my book’s Afterword—which has been excised—as a point of future reference.

Afterword

My friend took his life when he was twenty-three years old. After he died, I went to his home and read his suicide note—an unsaved document in Microsoft Word; a single paragraph with the cursor still blinking on his laptop. The document revealed a part of him that had remained hidden to me throughout our years of friendship, a longstanding depression that ended in his death. Staring in shock at the computer, I tried and failed to understand the sentences he’d left behind, realizing that I’d never truly understood the totality of his experiences. Around me I saw the grief of others through people broken into solitary halves—something previously whole now irreversibly split into two. There’s a face I still remember: it was the most pain I’d ever seen in a human being. I knew then the power of words.

Beyond the funeral, the image in his open casket stayed with me for weeks afterward: an imprint that demanded an explanation. I buried him that day, but I did not stop carrying his memory; the text of his departing note was more of a question than an answer, and the reasons behind his decision remained fundamentally mysterious. In seeing my friend’s body I had become closely acquainted with the annihilation of the self, but the reality of his suicide remained in the realm of abstraction. The sin of youth is that you always make everything about yourself, even the suffering of others. And, at the time, I could not understand his pain beyond the lens of my own narcissism—an emotional barrier that would take years to dissolve.

To survive, I coped with words: those of myself, and those of others.

I began writing—short, simple tracts at first; poorly developed essays that were an oblique, amateurish attempt to touch upon the subject of my friend’s passing. Mostly I consumed the texts of various academic philosophers, zooming in on the nihilists and the materialists. It was a particularly modern kind of avoidance: parsing a fundamentally emotional event in strictly philosophical terms. For years I delved into tomes of philosophy on an obsessive basis, eventually framing his death within a modern strand of scientism that abstracted my pain into a solely cognitive dimension. In this formulation—which one might well argue is our current cultural consensus—the combination of evolutionary theory and reductionism stripped away any substantive notion of deeper meaning from our lives. In spite of its deflationary character, the theory appeared to produce a clear answer to the question of my friend’s passing—under this rubric of conceptualization, it was simply a biological event that held no intrinsic meaning whatsoever (and thus, it could be easily exhaled and jettisoned into the past). At the time my mind mistook this abstruse pessimism for a kind of enlightenment, but in hindsight it was a deeply pathological form of coping—the singular elevation of a materialist horror perhaps best personified by the worst of Michel Houellebecq’s most depressed characters.

In the course of my studies I also took note of a related thesis embedded in the papers and books that I had compiled on my shelves: the idea that some reductive interpretations of evolutionary theory and incompatibilism might necessarily lead to a profound interpersonal nihilism—the type of premise so poisonous to basic human relations that it more or less makes them impossible to begin with. At the time I could not conceive of any valid response to these soul-evacuating theses, and I felt the weight of a burgeoning depression. Nonetheless, I was fortunate enough to have people around me who cared about my well-being and persuaded me to limit my isolated intake of philosophy and balance it with a healthy dose of lived experience, which returned a balance to my thinking that had been previously missing. I came to realize the many problems associated with certain esoteric modes of thinking abstracted from the warmth of daily living; that, if left unchecked by meaningful relationships with others—or alternatively, if fed by them—ideas could be too powerful a thing. Indeed, placing this in the context of my prior reading around Islamic radicalization, I understood certain ideas as so powerful that, in effect, they could subvert the autonomy of the individual, absorbing them into the tendril of a much larger egregore. It was around here that I discovered some of the outer fringes of the internet.

Initially I came upon the blogs and forums with surprise and bewilderment, recognizing the tenuous linkage between the rigorously argued nihilism of modern scientism with its amateurish, tangentially related cousins—fantastical extrapolations that ventured into extremely heterodox but clearly pseudoscientific beliefs (I realize, in hindsight, that the main benefit of philosophy is probably the learned skepticism, which can sometimes serve a kind of inoculating function). More broadly, I recognized the pain in these anonymous, digitized voices; the swirling vortex of torment, entitlement, and rage that seems so effective in activating the latent combustibility brooding in the minds of many a young man. The despair was beyond anything I had ever encountered in polite conversation. I asked myself—had I found the ghost of my friend?

No. I’d found something quite different.

Visualizing the complex mapping between these interconnected psycho-memetic nodes, I saw the strands of their thinking woven together into elaborate, intricate structures, congealing into a fragile tapestry that bloomed into the darkened shape of an extraordinarily turbocharged nihilism. Insofar as the depth of their pain resonated with my friend’s more generalized depression, I felt a tremendous sadness in learning of the scale of their distress, and yet, I could not turn away from the vast spectacle of these online spaces. A morbid ideological fascination grew within me, igniting a curiosity that I followed to its farthest textual perimeter.

I’ve long held an academic’s interest in radical or bizarre beliefs, collecting strange tomes to add to my ever-growing personal collection of fringe literature. Over the years, this research resulted in the thorough examination of many extreme psychological configurations (prior to my friend’s passing, I had spent several semesters deeply enmeshed in studying the ideological underpinnings of Islamic terrorism, analyzing volumes on what motivated young men toward radicalization). Now I saw similar patterns manifesting once again, this time in a different locality. Starting from a relatively simple set of priors, a person could be progressively radicalized into more and more extreme systems of belief that far eclipsed the merely academic texts of contemporary philosophers. It was the old adage about fantastical, elaborate delusions—these were largely internally coherent cognitive structures, seemingly requiring only a handful of premises to quickly scaffold beyond the realm of realistic possibility (above a certain elevation, confirmation bias does the rest of the heavy lifting).

Start with a relatively basic set of axioms, and, advancing through a carefully curated sequence of ideological exposures, additional axioms can be added in a stepwise fashion toward a specific end, feeding the needs of the psychological with the form of the memetic. Funneled into the wrong pathway, the result is a progressive movement along interlinked axes of extremism, escalating through beliefs in a manner that might seem awkward and non-sequitur from the outside but perfectly reasonable from the inside (and crucially, even scientific).

I continued writing. A contemporary novel about an angry, alienated young man soon formed within my small collection of notebooks, eventually expanding into a cohesive manuscript developed over many cycles of drafting and rewriting. I did not seek to recapitulate the biography of my friend—this book is not about him, and it contains no details of his life—rather, I sought to focus the story on a particular cluster of interconnected psycho-memetic nodes. I began outlining a detailed story, heavily referencing the viewpoints I had encountered online, imagining the possibility of a countervailing narrative structure that would comprehend the nihilism afflicting so many young men while offering them a way out of its terminal vortex.

I thought, in my arrogance, that I could save them.

Eventually, in the course of completing my manuscript, I came back to a moment of simultaneous personal and artistic reflection: I finally understood the centrality of reductionism as a mechanism for emotional evasion, and further, how this pathology had seemingly afflicted whole segments of our society. I realized the folly of my pride, and I saw my journey for what it was. I had only convinced myself that I had set out to help others, but really, I hadn’t been trying to help anyone but myself. It is said that writing fiction can be construed as a form of therapy, but in my case it was anything but. I had used language and philosophy to hide from the simple fact of my own avoidance, even constructing an elaborate novelistic ritual to further my own emotional intransigence in the wake of my friend’s passing.

So I stopped avoiding it. And when I stopped avoiding it, the ending of the story came to me as a narrative conclusion wrapped around the idea of meaning as inseparable from lived experience—as something wholly irreducible in constitution. I finally started seeing a therapist after years of dismissing the idea. I turned into the pain of grief instead of running away from it and finally allowed myself to feel the true weight of his loss.

I felt, at last, that I had buried him.

Of course, this was not the end of my journey. Although I had delineated the meta-structure of the story’s various chapters, much more work would go into the process of iterative editing. Over the span of multiple drafts, a terrifying sequence of male supremacist and white supremacist attacks strengthened my resolve to see the book through to its completion. Dedicating myself to a greater level of creative discipline, I focused the manuscript on the achievement of two simultaneous goals: (a) integrating philosophy with literary expression to directly addresses the question of nihilism, and (b) promoting the urgent task of deradicalization. I do not believe that these aims are antagonistic—if anything, I believe they are synergistic. In this respect my contention is that I’ve produced something unique in the domain of transgressive fiction, i.e. the coded opposite of something like The Turner Diaries, with the novel as an anti-manifesto: a countervailing narrative that reflects a comprehensive understanding of the empirical, moral, and political claims of certain belief-structures, while presenting a multi-modal critique of their steel-manned arguments. After investing a great deal of time into researching the psychology of extremism, I am convinced, like most others, that we do not possess a sufficiently thorough model of radicalization; as, insofar as acts of terrorism do occur, these are statistically rare behavioral phenomena that we have a very limited capacity to predict a priori. (Not coincidentally, the prediction of suicide is seemingly constrained to a similarly limited degree of efficacy). On the question of this specific brand of suicidal terrorism, our deficits in knowledge are miles deep, foundational. Most would argue that any model that fails in the task of prediction is not a particularly useful one and the true levers of mental causation remain just as mysterious as ever. This is perhaps an unsurprising finding: human beings are complicated. Nonetheless, we must admit the extent of our ignorance, turning to tools that are qualitative, immeasurable, and non-algorithmic—the tools of a spiritual exercise, the tools of an artist. The rest I will leave to the skills of the right professionals—who, sadly, remain systematically under-resourced across every state.

The reader of this work may question the artistic necessity of certain depictions of the protagonist’s views on women and minorities. Out of context, a superficial reading of certain passages might be miscast as an underlying sympathy for supremacist apologia or a desire to needlessly provoke reaction, but I do not believe that either of these negative interpretations is possible with a genuine reading of the story. incel is transgressive out of necessity, not out of a desire to shock or garner controversy. (Note, for example, that this story would only truly work in the first person.) I believe this to be fundamentally necessary in order to speak honestly about the condition of modern bigotry and its tethers to nihilism: that it is needed to transcend the object-level critique and engage the recipient on more mobile layers of persuasion. Some might contend that the horrendous acts perpetrated by certain ideologically motivated individuals preclude the possibility of any degree of complexity beyond the simplified narratives that prevail in mainstream coverage of terrorism, but it is this same complexity—and, ultimately, the understanding engendered by it—that is vitally important to advance the project of deradicalization everywhere. In some ideologies, the taking of a life is the result of a twisted affirmation of life’s underlying meaning and value. In others, the taking of a life is the result of a universal denial of this very possibility.

I believe that our modern affliction—the characteristic disease of our time—is the latter.

Here my thoughts turn more discursive. Given the now well-particularized mechanisms of specific attacks, mimetic contagion seems to clearly be a driver, yes, but it’s arguably only the terminal link in the sociocultural chain of causality. In the face of such overwhelming repudiation of the value of life, what cultural counters can possibly be brought to bear? Simplistic methods of moral condemnation are necessary but insufficient, and absolute state-level control of the memetic commons is neither possible nor desirable. The process of radicalization still continues, largely unabated. (Could it be that this affliction extends beyond the material? Beyond the obvious variables of mental health, could it be that its roots are existential, spiritual, or even para-religious?). At the most vulnerable margins, the process of deradicalization is uninterested in the universal language of condemnation—it is interested in the particularities of change. In so doing it is not my desire to conflate trauma with bigotry, but to walk men back from the precipice of a spiritual chasm from which there is no return. It is here that art can seed the cracks in a rigidly determined worldview that is epistemically closed from the full spectrum of human experience and the genuine possibility of positive meaning. This requires dispensing with reductive, solely pejorative models of radicalization, and recognizing that shaming someone does not work when their identity is rooted in shame.

The book in your hands is the product of a journey that began with my friend’s passing and ended in the form of a paperback novel. It was written in an effort to impart meaning to the lives of young men who feel that they have none, turning them away from the path of death and destruction and toward the path of healing. I give it to you, the reader, in the sincere hope that you will understand its message and reject the twin sirens of rage and nihilism, however tempting they may be. Man cannot live on anger alone. Whatever deep, dark hole you are in, I wish you light.

Yes, I’m aware of the very high-profile exchange he had with Sam Kriss on here lately. I of course do not agree with his views on Gaza, but I often find his geopolitical commentary in podcast interviews very entertaining, particularly when he criticizes the state department or American interventionism. My views on most topics are syncretic and I find right-wing critiques of American imperialism quite fascinating even though I’m a conventional anti-imperialist on this specific issue (i.e. a leftist). Yarvin’s views on geopolitics are doubly interesting since Thiel, who funded Urbit, is a known uber-hawk on China. Not a typical client-patron relationship, I’d surmise.

No, I am not endorsing male supremacism or claiming that they’re completely harmless, I’m only making a relative comparison as borne out by the data.

I was also needlessly paranoid that if a large number of people read my book, there’d naturally be that one guy who didn’t get it, and I felt an obligation to make sure that the book could never be misinterpreted. In hindsight, this was wholly unnecessary: the text is simply too dense and complicated to admit a surface-level interpretation of the narrative as an endorsement of the character’s worldview and any readers who might be prone to that are just going to get filtered out very rapidly.

For a very interesting and counterintuitive view of what motivates school shooters, read this Kantbot article: https://mindseyemag.com/magazine/kantbot-guns-dont-kill-people-school-psychologists-do/

I've read somewhere that one of the most accurate predictors of future social upheaval is a large population of sexless young men. Perhaps that's the real reason why they're persecuting any man who doesn't have a girlfriend.

Have you listened to professor John David Ebbert? He can be found on youtube along with his online courses.

He is great at giving overview of Oswald Spengler and a dozen others. Our Western Civilization has a proper name that noone lnows. It is Faustian Civilization. We made a pact with the Devil for temporary unlimited power and wealth and gratfication. Our art is the inlimited horizon. All we know is expansion. The greatest achievement our particular civilization could achieve is placing a McDonalds franchise on the Moon… I mean Mars… I mean on Alpha Centari… It is all so tiresome. Please make it stop. Russian Culture has suffered arrested development and is overdue to be the next great culture, accorsing to Spengler.