Ross Barkan's 'Glass Century' and the agentic twins of protagonist & writer

human agency in both simulated and non-simulated forms

Ross Barkan’s Glass Century debuts today.

It’s an ambitious multigenerational novel that’s interesting not merely because of its depth but also because of its timing: it’s the kind of book that you just don’t see attempted very much anymore.

Glass Century primarily follows the life of Mona Glass, a young, headstrong woman living in New York City in the early 70’s.

The books spans several epochs in the city’s timeline and while there are quite a few opportunities here for traditional literary analysis, for me, the most important distillation comes down to a single needlepoint of an idea—and it’s not the obvious thing you would draw on (which is the book’s engagement with the confluence of human and urban time).

Imagine a pyramid of literary analysis that sequences something like this: descriptive prose → dialogue → characterization → plot → themes → meta-themes. Now, at the highest possible level of abstraction—at the summit of the pyramid—the biggest theme of Glass Century is arguably its conception of human agency and its connection to the effect of living in New York itself.

Some background first.

For me, the appeal of literary fiction doesn’t merely draw from the aestheticism of it, but also of its ability to create a kind of holographic simulation in the mind of the reader. The simulation isn’t a 1:1 drawing of reality, but a narrative superstimulus: an accelerated presentation of the stream of consciousness where pivotal events are timeline-compressed and actions are therefore magnified in their consequences.

As a general rule, the most compelling simulations trend toward active protagonists whose sense of individual agency often exceeds ours. Note that this need not expand into the area of fantasy or outright escapism. It’s not so much about the “hero’s journey” as it is about the magnification of regular life and its pivotal choices: characters act in their world, their choices have (highly variable) consequences, and these consequences beget another round of pivotal choices.

In modern conditions, the speed of this cycle often feels slow, drawn out, and the opposite of agentic: days and weeks and years of living through automatisms and longitudinal life-scripts where we glide by on-rails.

What makes Mona Glass an interesting character is not any fantastical account of her being a notable figure in the cinematic sense but merely the feeling of her choices. The novel’s juxtaposition between its protagonist and the city seems to present an implicit commentary beyond the traditional tropes of New York as a place where “anyone can make it,” but rather, of the city as a kind of ambient leverage on your freely-willed choices, a sort of environmental multiplier that magnifies human agency beyond its normal parameters.

The thing that’s special about New York isn’t a function of its network effects in publishing or finance or anything else, but in the actual feeling of these effects: almost by magic, there’s an ambient, expanded freedom of action that you get from the place, one that gets activated beyond a certain threshold of energetic urbanism.

This, for me, is the very subtle and hard-to-articulate beauty that leaks through the metastructure of the novel. If I were to connect it to a cinematic analogue, it calls to mind the ending sequence of Gangs of New York and it’s time-lapsed montage of urban evolution that, like Glass Century, seems to pose the exact same question—what is a city other than amalgamation of stories?

How many great stories have bloomed (and died) in this vast grid of streets and skyscrapers?

Glass Century even seems to gesture toward an account of New York as a kind of super-agent: a kind of sprawling narrative superstructure that directs the flow of the entire country, like some enormous magnetic compass pointing in a certain direction.

This was what I liked most about the novel, and in particular, in the way this came through its ending.

Let me digress: I spent a fair while debating how to approach Barkan’s novel in my Substack. First, there are already a surfeit of reviews that have emerged, which include recommendations from Pulitzer prize winners (Joshua Cohen) and a glowing review in The Wall Street Journal. I didn’t want to approach things too directly when differentiation is always my prime directive for this blog.

Second, I had the privilege of reading a late-stage version of the manuscript when it was already very close to publication. My notes were really quite simple: it’s a serious, elegantly written novel that’s interesting in part because it seems to entirely lack a true contemporary—I’d have to go back about 15 years to think of another novel in this category. (I’m talking about Franzen, Foer and so on).

So, to put it in somewhat crude terms: how many guys under the age of 40 are currently putting out novels like this?

I suppose we are all by now somewhat tired of the discourse around the decline of fiction by (and for) men. Of course, this discussion was at some point important to have: sometimes the dog that didn’t bark is the most interesting thing to talk about!

Now, a new consensus has appropriately emerged: it’s time to lean away from discourse and lean toward production.

And production, for a guy like Barkan, is really no problem at all.

Perhaps what’s most interesting about him as a writer is how agentically he has approached his own career as a novelist and writer. In this manner it’s hard for me not to place him and Matthew Gasda in roughly the same category: to me, these guys seem self-made in the agentic sense.1

What do I mean by this?

I mean that guys like Barkan are as much engines as they are writers: they press forward and create their own networks and opportunities. Nepo-babies they are not.

For those of you who hadn’t read him yet, Ross regularly contributes top-shelf literary criticism on Substack, and his breadth is one of the things that makes him a compelling writer: any objective evaluation of his placement would situate him somewhere on the vertical slope of the power laws in the attention economy: for one, he’s an unusually successful journalist with tens of thousands of subscribers.

If you have any level of engagement with writing, you would know how difficult it is to enter that tier of attention.

That he also writes very eloquently about the honesty of literary ambition or about the underrated benefits of pro-social co-operation between literary writers indicates a level of versatility that’s very hard not to be impressed by.

Lastly, Barkan goes out of his way to elevate other small, niche writers, including yours truly—for which I am deeply grateful for. As much as I can, I try to pay this forward by recommending books by other writers who I feel deserve a higher profile: Udith Dematagoda, Alan Rossi, Dan Baltic, Mattp969, Cairo Smith, Jack BC, Tooky's Mag, and many others come to mind.

The body is a form of literary interiority

A coda, then, to Mona Glass’ representation of human agency is the way in which she inhabits her own body. Agency, in its most fundamental sense, is a physical thing, after all: when a unicellular organisms exhibits agency, it is always through movement, not computation.

Even speaking is a form of movement!

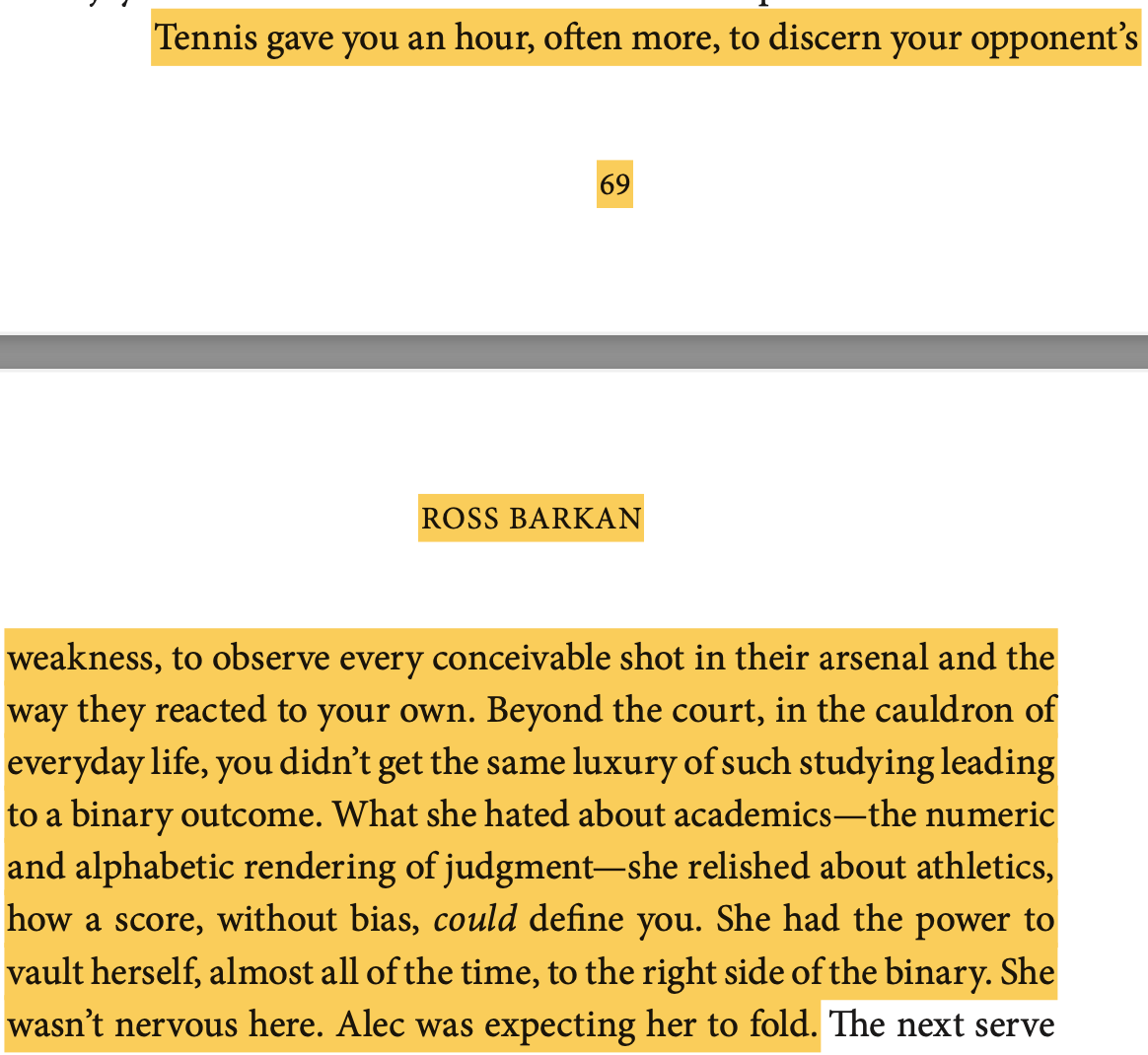

Thus, my favorite sequence in the book (apart from the very ending) is actually a tennis battle that appears about one quarter of the way into the novel.

The easy analogy here would be compare it David Foster Wallace’s famous profile on Roger Federer, but a (much funnier and perhaps more subsconsciously accurate) comparison would be to psychoanalyze Ross and speculate that he unconsciously drew upon some of the genre-defining battle sequences in Dragonball Z, which he grew up enjoying as a child.

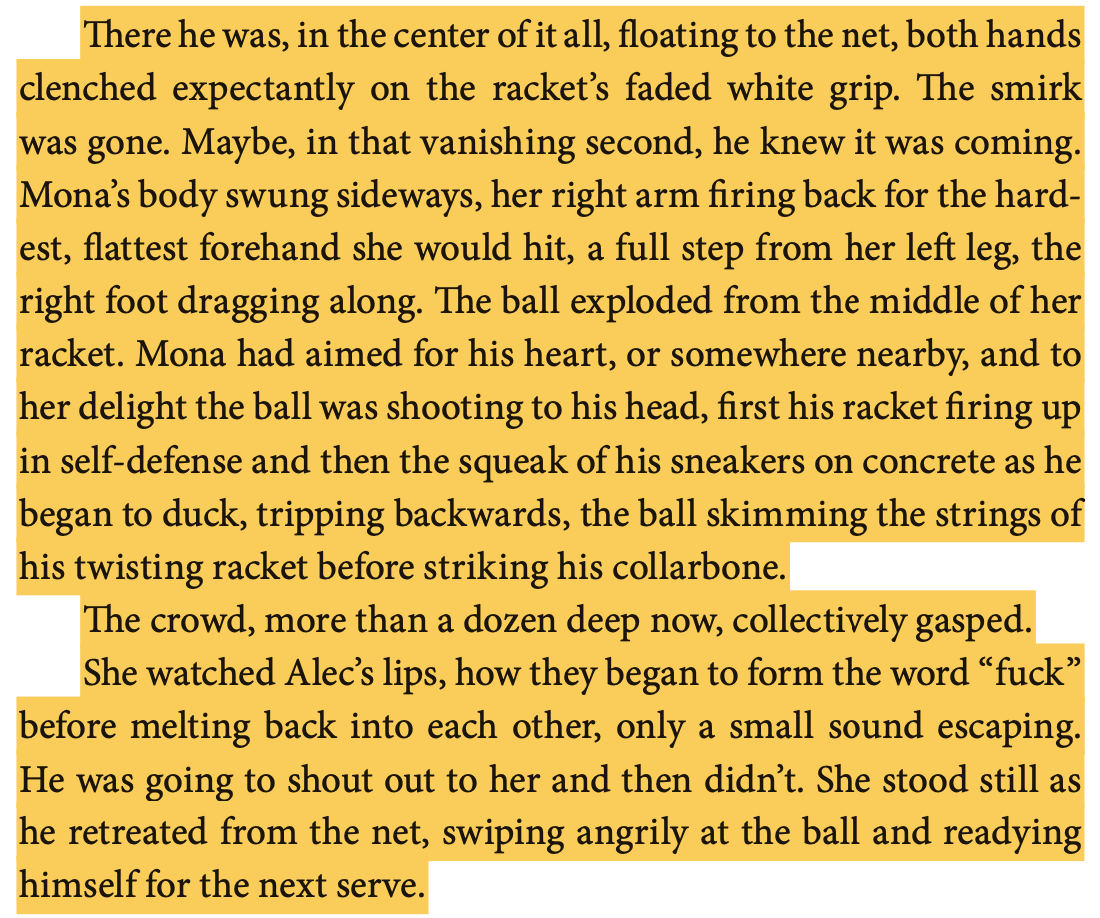

The following description, for me, carries the tiniest perceptible inflection of a deeply hateable Japanese anime antagonist:

I read the tennis battle end-to-end standing in a queue for something which I barely remember because I wanted this character to lose so incredibly badly.

The integration of Mona’s strategizing during this scene reads like a war—which is one of the reasons I liked it so much.

The joy of reading fiction as a literary writer is that you can appreciate the craft of composition with another layer of appreciation: you have a more intuitive sense of how difficult it is to do something.

In the age of high-fidelity cinema, animation, and CGI, it’s often said that the novel is an obsolete technology for depicting visual action.

I agree with this judgment—but I differ on a single detail.

While the novel may no longer be as salient for depicting visual action, it’s irreplaceable for inhabiting physical action, because living in your body is moreso a feeling than it is a observation.

Notice the way Barkan seamelessly moves between proprioception (internal awareness of the body), antagonistic strategizing (guessing what Alec is thinking), and the actual events of the tennis battle.

This, to me, is a beautiful exercise in craft that demonstrates the magic and beauty of prose fiction: of its ability to seamlessly migrate from interior to exterior and back again, like a stream that is continuously changing course.

Rebooting literary culture with high-agency, “live-players”

I recently came across an interesting tweet by Matthew Zeitlin (no idea who this guy is) about the decline of literary culture and thought it was interesting.

What’s salient about this take isn’t the prediction itself, but the sentiment behind it: the decline of jazz is a function of its irrelevance, and its irrelevance is a function of its lack of energy.

And lack of energy is downstream from lack of agency.

The passivity of traditional publishing is infuriating.

Essentially, it comes down to waiting for permission?

Dear agent, can you please read my book?

Dear editor, can you please choose my book?

Dear sensitivity reader, can you please approve my sentences?

Dear Twitter, can you please tell me I’m good?

And so on.

Look—I don’t know what the future holds for the medium of the novel, but increasingly, my gut says that it won’t quite go the way of jazz or classical music. Even with the progression of high-fidelity AR and VR narrative immersion, my intuition is that narrative text is just too strong of a cognitive anchor to get obsoleted in the way that a specific musical genre can get turned over and obsoleted. The proper analogy, then, would be closer to music itself going the way of Jazz (not just one specific genre within it).

If the novel is to have a future—and I believe that it will—it will be because people like Ross and striving and building from a well of energy that compounds into a sincere regeneration of the form itself.

And I’m all for it.

(if not in the literal sense—but only because it’s sort of logically impossible to be “perfectly self-made” in the artist-as-prime-mover sense of the term)

Dude, I am begging you to stop using the word "agentic." Begging.

Clearly you are a smart guy and Barkan is a terrific writer. Many of the things you said are unarguable, or to argue them is to take the side of the devils versus the angels. There is however an inherent blindness to this kind of writing and the critique's stance. The fact is, nobody, outside of an elitist clique, or New York wannabee's, are going to bother to break this syntax down and glean any meaning from it. It is at heart, classist and requires a certain degree of educated appreciation for an esoteric and fenced activity. Readers, if they want, can participate vicariously the way they can particpate in pornography or any writing that is physical at its core, bu why would they? The tennis passage reminds me of Tolstoy's Lev cutting wheat or Updike's Rabbit, taking off his restrictive jacket to play ball with some random kids. In each instance, there was a deeper sub meaning to the text other than the integration of the physical and psychological moment. Until the novel can rebuild its foundation in some kind of ideological relevancy, it's a pointless exercise in classism, and going the way of the dinosaurs may be the best outcome for an outmoded form.