Podcast appearance - LEAFBOX (March 2025) - Diaspora musings

A more wide-ranging conversation about literary art, geopolitics, sino-accelerationism, and diasporic writing

I recently did a podcast with LEAFBOX. Listen to it here:

But first: some review-related updates over from DECENTRALIZED FICTION:

David Sessions put up a nice review of my novel, INCEL, on his blog (thank you David!):

I recently finished Matthew Gasda’s The Sleepers, which I very much enjoyed. A full review will come in due course, but I can’t help but think it’s the apex Postliberal Book Reviews-type-of-novel: a truly savage indictment of the spiritual dead-end of urban pleasure-seeking-as-a-lifestyle. I saw parts of myself and many members of my own generation in this. If I were to describe the book in word one—damning.

I’ve acquired review copies of The Agonies by Ben Faulkner and Stop All the Clocks by Noah Kumin. Full reviews in due course.

I plan to review the novel Fedbook later this year, but we’ll see when I get to it.

Now—on to the podcast.

Lastly, I put out a request for further posts. A lot of people asked for more posts about indie publishing and book reviews, so these themes are going to get hit more in the near future.

A summary of my conversation with LEAFBOX

Some things we talked about, excerpted from his post about our dialogue:

the counterbalance to techno-feudalism, the shifting Overton window, on deep (racial? / psychosexual?) anxieties of Western elites over China’s technological rise, transhumanist cults, the internet as a pathologization engine, the problem of male agency in a world trending toward simulation, the accelerating breakdown of ideological coherence, the future of literary fiction in an era of digital feudalism, the aesthetics of niche subcultures, on panpsychism for story building models, the seduction of AI worship, Grand Theft Auto as contemporary American reality. On paranoia, the next phase of cult formation, social engineering, why the next big cultural divide won’t be left vs. right but human vs. post-human, and why it’s enough to just be read by a small group of considered minds in a literary salon scattered across the digital ether… + more.

Part of the undercurrent of our conversation came down to the question of it means to be an Asian-American novelist in an era of extreme technocapital acceleration from both Western and Eastern poles.

This is one of the reasons I’ve become so intensely fixated on geopolitical and technological competition.

At the risk of being reductive, I have a two-level view of this genuinely-titanic struggle:

On one level, the competition between the United States and China is a contest between a hegemonic Western technofeudalist oligarchy (the US), and a Sinic communist techno-authoritarian party powered by the engine of state-capitalism (China).1

On a deeper level, it’s simultaneously a racial conflict between Western Europeans and the Han race.

At level 1, the competition takes on all kinds of interesting dimensions. Technofeudalism (closed-source AI, centralized in US frontier labs), vs. Communism (open-source AI, distributed and decentralized from PRC frontier labs).

The latter contrast is hilarious kind of narrative violation about who truly has the “right to compute” in these opposing political systems, but maybe we shouldn’t be surprised that a communist state believes in open-source software. It does seem like there’s a certain ideological alignment there, doesn’t it?

Now: let’s talk about the racial angle.

World War 3 is a race war and we can stop pretending it’s not going to be

One of the simplest ways to model sentiment around racial or geopolitical conflict is to see what kinds of ideas gain traction on social media. When something achieves meme status, it means that a non-trivial percentage of the population has anchored on the emotional traction of a particular war-related power fantasy (these trend toward various forms of genocide).

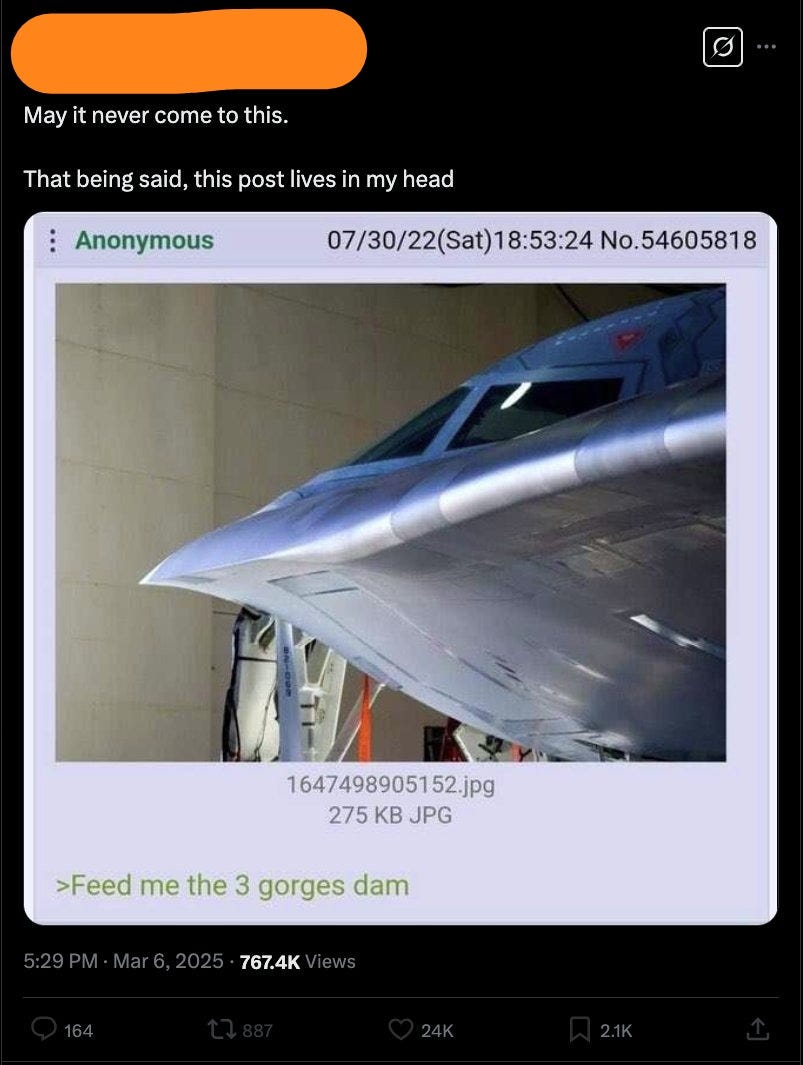

One of the perpetual tropes you’ll encounter on the Twittersphere is the idea of air-striking the three gorges dam in the event of a US-China war over Taiwan.

I’ve seen it often enough and people can hardly contain their raging enthusiasm for the idea.

Here’s what Grok says about the expected casualties from such an attack, both direct and indirect:

It’s hard for me to gauge his deep this kind of racial animus is.

My intuition is that anti-Asian racism in the West is not currently very deep, but that it could become very intense in the event of a hot war with China.

Simply put, the American psyche is not remotely ready to sustain severe aeronaval losses of prestige platforms like aircraft carriers, F-35’s, and so on.2 At both the level of mass politics and the level of the White House, it is not psychologically prepared to lose.

This is what makes the political situation so profoundly dangerous: it means the reaction function will be very extreme in both domestic and foreign theaters. It could easily go nuclear.

A simple question for Asian-Americans:

Do you know what time it is?

Neo-China arrives from the future and diaspora navel-gazers are not ready

"When people see a strong horse and a weak horse, by nature they will like the strong horse."

Osama Bin Laden

When I came to the West as a young boy, neither my parents nor myself had any regard for our home country of birth.

Whereas Japan, Taiwan and Singapore had notably already achieved a great deal of economic and technological progress, China was a sort of shameful laggard we rarely ever talked about.

One of the ideas I mentioned during this podcast was the idea of technological power as a surrogate marker for racial power.

As a boy, I remember picking up issues of Popular Mechanics and marveling at images of the US Carrier Strike Groups sailing the ocean. I was entranced by the image of it.

The thing about power is that it forms its own argument. This argument tends to be irrefutable.

Flashback to the unipolar era: history, at the time, was utterly over. The Liberal imperium would last indefinitely; the Chinese back home would toil in 16-hour factory shifts and make us shoes until the heat death of the universe. Those of us who had left were the lucky ones: we’d escaped into the material comforts of the continental United States and the universal appeal of capital accumulation.

When I was 13 years old, I spent six months learning (and failing) how to skateboard. There was a 12 to 24 month period of adolescence where I think I rotated through every possible permutation of millennial boyhood that was available at the time (in the end, I landed on none of them).3

In the past couple of years, things have changed somewhat dramatically.

It started with EV’s but it’s progressed to humanoid robots, two sixth-generation fighters, and now Deepseek.4

Here’s a take that I think will be proven correct in the next couple of years:

Here my hypothesis is simple: Nick Land was right about the Chinese, and we are all catching up to it.

The reasons for this are multifactorial and have been variously attributed to a combination of a effective industrial policy, high-levels of communist state capacity, and most importantly, a very deep bench of human capital in the STEM department.

Steve Hsu has written numerous times about the most important upstream inputs for Chinese technocapital acceleration: they have more engineers than we do. This means that sanctioning them won’t work because they’ll continue climbing the tech tree with indigenous talent alone. This follows from simple first principles; upstream of innovation is human cognition and the political and economic systems to co-ordinate them.

Hsu argues that stopping them is too late: the Middle Kingdom has reached escape velocity.

Now, if you follow any Asian-American literary writers, none of them are talking about this. Absolutely none of them appear to be talking about the most significant geopolitical shift underlying the entire relationship of the United States to Asians, and by extension, Asian-Americans.

As a class, these people are completely out of ideas: aesthetically, culturally, ideologically. The Fukuyama train has derailed and they have yet to crawl out of the wreckage of it.

They’re laggards of a different kind.

Consider the following short story: Dorchester, by Vietnamese-American Steven Duong:5

What is Dorchester about, exactly?

Nominally, it starts with an account of anti-Asian hate crimes (written in the most generic, reality-avoiding manner possible), but as you press forward into the story, a central theme is the Asian-American male protagonist being leashed by his girlfriend.

Look—how many times are we going to do this to ourselves?

What’s the point of this kind of story?

I actually enjoyed Dorchester—I think it’s written very well—but we need some new ideas here.

I don’t know anything about Duong’s background: whether he’s Chinese, Vietnamese, Chinese-Vietnamese, etc., but I feel he’s emblematic of an entire artistic cohort in the diaspora.

If I could describe them in a single sentence, they are people who are not paying attention.

There’s a certain type of Asian-American who is so implicitly married to the matrix of American exceptionalism and cultural liberalism (and their comfy place within it) that something breaks in their brains when they see the sovereign East growing in technological and geopolitical power.

It’s a narrative violation that activates a cognitive dissonance so disorienting that very little makes sense anymore.

It’s one thing to be a minority from a poor country. This type of low-agency identitarianism fits into the glove of progressive politics and our near-total lack of domestic political power.

But—it’s another thing to be a minority from a peer competitor to the United States of America.

These situations are precarious, but in opposite ways.

The essential characteristic of the contemporary Asian-American is that he or she is conquered. This explains (in part) why the West loves Korean and Japanese cultural exports—these countries are occupied and subordinate to Anglo-American power.

I want to be clear about what I’m saying here: the answer to Asian-American anomie is not a form of reactive Sino-Triumphalism, or worse, a mirror-image of domineering ethnonationalism or ethnosupremacy. It’s merely a conscious decision to relinquish deeply held notions of your own inferiority.

And that is a starting point, not a destination, for something generative.

Literary fiction is a niche hobby that will never regain its peak cultural significance and that’s okay and we should stop whining about it

Why care so much about books?

Why care so much about literary fiction, an admittedly niche hobby that might well mostly die out with the last literate generation (millennials)?6

For me, the answer is simple.

The novel is a beautiful form of art, and one with unique strengths over and above other narrative forms.

Wordcels of every race have a duty to preserve it.

So long as small circles of people continue to cultivate and participate in this organic ecosystem—so long as it is not gone entirely—it remains a worthwhile enterprise and a genuine source of meaning.

N.S. Lyons has argued that these are convergent systems but I’m only partly convinced.

This is what happens in every war game, and I’m increasingly convinced the war games are wildly overoptimistic in favor of the US. The Chinese apparently have a factory that can produce 1,000 cruise missiles a day. We will run out of missile defense interceptors, ships, and aircraft before they run out of cruise missiles. We can’t beat them off their own coast without going nuclear.

This is why I liked the film Didi so much.

I’d recommend Alex Kaschuta’s podcast with Steve Hsu on the topic of the US-China AI arms race if you want a good primer.

Thank you to Christian Lorentzen for flagging this story for me - I’ve been meaning to mention it for awhile.

Apparently the data say that Zoomers are functionally illiterate when it comes to reading. Is this true?

Regarding how Asian-Americans haven’t internalized the rise of China in their own self-conceptions, I think this is only partially true. Where it’s most true is among the Asian-Americans that are assimilated into elite or middle-class society, which means assimilation into liberal globalist society, in where racial identifications that are too strong are either a sign of low-class deplorableness or anti-Asian wokism. Also, if you’ve already spent so much effort to assimilate, then reaping the benefits of an identity you’ve disavowed feels false in a self-serving way, so there is perhaps some intentional self-denial in order to minimize regret for actions that can no longer be changed.

It remains to be seen for the next generation of Asian immigrants, but it should be noted that status doesn’t really accrue from national GDP or military might, but is currently more a factor of per capita GDP or cultural cachet, which is why historically Japanese and now South Korean heritage is higher status than Chinese, which is itself higher than South East Asian.

Finally, from a game-theoretic viewpoint, angling for more political power of status results in a U-curved utility function depending on your current political power: if it’s obvious that you will win then everyone will get out of your way; if you're small enough that you aren’t a threat, you can be incorporated into someone else's a coalition; but anywhere in between start a fight and results in backlash and repression.

I’ve think you’ve hit the nail on the head on most though I would say the west begrudgingly consumes Korean and Japanese goods when it affirms their dominance and specific things at the suggestion of mostly white men. Asian women’s bodies being the most popular suggestion.

I cycle through the pitfalls you mentioned on a regular basis. But as a Korean American, they are somewhat different - our delusions of grandeur are naturally limited by geography and history reminds us to walk a fine line.