/newwave/ review - Matthew Gasda's 'The Sleepers' and millennial goonerism as a terminal spiritual malady

I've got thoughts on this one.

Preamble: We might as well dispense with blurbs in general

Depending on how fast you read, a good novel will subtract anywhere from five to fifteen hours from your life.

This is not so much a utilitarian calculation as it is a aesthetic and spiritual one—the question you have ask yourself before you commit to reading a novel is whether or not it will give more than it takes.

Will it add a certain richness to your stream of consciousness?

Or will it merely consume units of time?

Because I’m an obsessive, I find it difficult to start (but not finish) a novel.

To me, the act of giving up on a book feels incorrect and abortive; like pausing a simulation that’s meant to progress to its natural and deserved conclusion.

Time is a generally a good filter for choice of literature: it’s easier to select books that have persisted in their readership over the years. Good works tend to accumulate (rather than lose) their reputation over time; it’s almost as if literary merit exerts a kind of anti-entropic force as the years roll by, progressively burnishing their stature in the pantheon.1

With contemporary or recently-published works, selection is a much harder enterprise.

As with any form of art made by human beings, a lot of literary fiction is basically dog shit.

The problem comes down to your heuristics for choosing what to read. If you were to assume that blurbs are a genuine indicator of quality, you’d have no idea that this is the case.

The basic problem is that a lot of shitty books have excellent blurbs.

The reason for this is simple.2 Currently, literary fiction is a small, shrinking market.3 In a previous era, where literary novels had much wider reach and much deeper cultural impact, the market was large enough to support “PvP” rivalries— “player-vs-player” or writer-vs-writer conflicts with savage takedowns of various novelists by prominent critics.4

Back in the day, a larger market could support a larger critical commentariat and you could advance a career in literary criticism with a bit of headhunting.

Now, because the overall size of the literary fiction market has become smaller, economic imperatives toward back-scratching reciprocity are greater. The game has shifted from PvP into “PvE” (player-vs-environment), where the real competitors consist of a multitude of dopamine troughs like TikTok, video games, social media, and so on.

This has the effect of turning the game into a more co-operation-oriented strategy. The problem with excessive co-operation in the publishing market is that it can also drive a form of literary cronyism which rapidly devolves into a circlejerk of incestuous back-scratching.

Here’s how it works: like fine art or other form of high culture, literary fiction is partly a status game.

Status is conferred when someone more established than you says something good about your novel—this can be a blurb, a review, or a social media media post. This person might be a critic at a magazine who also has their own novel or essay collection that has either already been published or is soon forthcoming.

This creates a strong incentive structure to say good things about novels written by your friends because there are so few notable people to begin with.

This isn’t an altogether conspiratorial element, but a matter of simple survival—a sort of banding together and a form of positive-sum competition.

Because I started out as a completely marginal figure, it’s been surprising how friendly and receptive other writers in the alt-lit space are. There’s a sense of genuine camaraderie and community—even in a purely online dimension. And I don’t want to diminish the beauty (and value) of this.

But we have to acknowledge its downsides.

Literary podcasts like Tooky's Mag or Book Club from Hell do an admirable job of maintaining objectivity and not being overly laudatory of indie works. I think Mars Review of Books and The Metropolitan Review also work hard at this too.

See?

I’m doing it right now!

All of these teams have either published me or said positive things about me.

And here I am saying good things about them.

Of course, that’s my sincere belief—but you can’t say that I’m not (in some way) biased on the matter.

Disclosures: I’ve never met Matthew Gasda and he is not my best friend

As you can guess from scouting my profile, I don’t live in New York City.

I’ve never met Matthew Gasda and I’ve never been to a trendy literary party in Brooklyn. Of course, I’ve followed the brouhaha over Dimes Square but I’ve never been a scenester or made an appearance in washed-out polaroids with e-girls doing a post-ironic pseudo-duckface.5

I really have no commentary about the (now defunct?) Dimes Square scene that was (presumably?) anchored on various bon-vivant personalities and micro-celebrities. Whether by choice or by journalistic fiat, Gasda is inextricably tied up with the “brand” of Dimes Square, but I don’t think any of that is particularly relevant to his novel.

The book should be evaluated on its own terms.

Granted, it’s not as if I can erase all context on the subject. I’ve lightly followed Gasda’s career—from a distance, having never seen one of his plays in-person—and I’ve always been impressed by the way that he bootstrapped his play-writing career out of performances in an apartment.

From my perspective, that’s the kind of high-agency scrappiness you just have to respect as a writer.

Thus far, we’ve exchanged a few friendly DM’s on his body of work, which is how I got access to an ARC copy. As a matter of process, I have not shown him the review prior to publishing it. It’s possible a colleague of his will help me put out a short piece later this year, but I haven’t written it yet and probably won’t have time to because my shitty drop-shipping business that (marginally) keeps me out of absolute poverty has just been nuked by the Trump administration.6

That does not mean that I am entirely without sin.

Like my periodic correspondence with other established writers, I’ll freely admit that even DM’ing someone at this level gives me a frisson of “I’m in the scene now” and so on.

Recall that I started as a complete outsider. Even the most minimal acknowledgement creates low-level glow in my validation-circuitry.

Even though I love the Gasda-affiliated Arcade Publishing, my next novel is probably going to be a lot more spicy than my first one, and I don’t see any traditional publisher realistically backing its release.

Even so, as I write this, a little voice in my head—a little Wormtongue—is asking what might happen if I ingratiate myself with Arcade-affiliated writers.

Might that help me out down the road?

I think it’s reasonable to be honest about our biases as critics and to openly acknowledge them.

The stakes aren’t exactly high, but it’s good spiritual hygiene nonetheless.

So now you know where my biases lie on the matter.

Let’s get to it, then

I’ll start with the verdict, and then we can talk about specifics.

I liked The Sleepers a lot and I think it’ll stand the test of time as one of the more important and lasting literary novels of this millennial era.

My view at a high level is simple.

As millennials continue to age terribly, The Sleepers will increasingly read like a coda to the dead-end of our cumulative cultural mores: an incredibly damning indictment of our hedonism and the hollowed-out playground of modern liberalism in the meaning shredder of New York City.

If Tony Tulathimutte’s excellent Private Citizens augured in the millennial literary generation, The Sleepers puts it to bed—or, perhaps more accurately, it puts a bullet in its head.

There’s so much to say about this book that I have to start out by mentioning the style in which it was written.

For those of you who’ve read my own novel, you’ll know that I’m a fan of maximalism and all of its stylistic conceits. Think American Psycho with its detailed, overly descriptive prose and lengthy, run-on sentences delivered in a very intense, forceful voice.

In contrast, Gasda’s lyrical restraint and minimalism isn’t an unusual style for his generation of novelists, but there’s something unique about his particular form of minimalism.

What’s particularly interesting about the style of The Sleepers is that it’s written like a novel but often feels like a play. It’s an incredibly unique structure that is hard to describe even with an excerpt—you have to zoom out and view the manuscript from a satellite-view to see it.

Essentially, the individual dialogue scenes between characters run for much longer than what you’d typically see in most novels—for the most part, rather than this being a detriment to the narrative, it’s a strength of the book.

To the extent that some of these scenes periodically drag on for too long, it’s a minor flaw in a very tightly-written book that abjures trendy prose-level flourishes but is impactful and devastating all the same.

Cum for the cum good: wire-heading as the dead-end of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness

Here’s a segment from the first page of the novel that describes Akari, a hapa millennial:

In a sentence, we already see the portrait of the millennial as the ur-gooner: a human-optimization function aimed at the pyramidal structure of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Already, Gasda seems to present a hypothesis around this psychological structure: is the capstone of the pyramid truly this thing we call “self-actualization”?

Or is it really something more based?

Is it really about cumming as much as possible?

Be honest, now.

Like many of us, Akari is trapped in the ouroboros of experiential pleasure: the screen presents the viewer with various possibilities of hedonic experience.

Thus, all the striving that exists within us is there only to collapse the distance between the these sexual and non-sexual flavors of televised pornography and the optical feed that is your actual lived experience:

Then, we zoom out, and Gasda presents the playground of the city: the “IQ-shredder” of TFR-zero and it’s orphaned, non-reproductive ejaculates:

The problem with this model of living, of course, is its intrinsic vulnerability to entropy.

There are many readings of this book that are valid, and it’s not an aggressively (or even overtly) natalist novel.

But insofar as it presents a broad critique of liberalism, it’s hard not to make the subsequent inference as a reader. Whereas reproductive systems are life-giving, hedonistic systems are, on net, life-subtracting—simply because they degrade over time.

We’re deep within Chesterton’s-Fence-territory here—whether we like it or not.

Here we begin to add characters: Akari’s hapa sister, Mariko (a failed actress), and Mariko’s leftist-academic boyfriend, Dan—and we begin confront the brutality of the millennial operating system and it’s two failure modes of (a) getting what you want, and (b) not getting what you want.

Friends!

What happens if you reach the peak of the pyramid—and there is nothing there?

Or worse—you never make it to the top of the pyramid at all?

The problem with self actualization as a life strategy exceeds the comparatively simple implementation of hedonic wire-heading: not everyone can be equally high-agency. Because human agency exists relative to other agents, it is zero-sum. It’s not just about the limited number of Dunbar slots for prominent people—it’s an even more essential feature of agentic competition in any sphere, whether artistic or not.

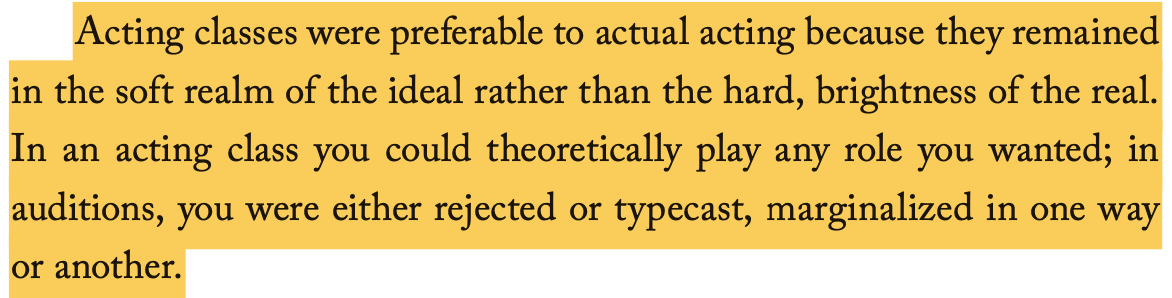

This ruthless tournament of competition is most acutely true for actors:

The most important question to ask about a novel is whether or not you enjoyed reading it—whether or not the experience resonates on an aesthetic level.

With literary fiction in particular, there are complementary ways to achieve this end.

Broadly speaking, you can anchor on the sentence-level and craft beautiful prose with complex or inventive metaphors, or you can anchor on the meta-structure and lean into voice as the emergent property of the text.

Gasda’s clean, straightforward style has almost no flourishes in the former category, but his command of human interiority is precise, incisive, and resonant with the bare-metal facets of human psychology.

Interestingly, the book evades any sort of conflict-axis when it comes to examining the social and cultural problems of millennials. It’s tone is neither progressive nor reactionary, but passively descriptive.

The feeling is something of a dispassionate syncreticism that views our pathologies from an ideologically perpendicular angle - this is another reason I think it’ll last in the years to come.

It’s examination of race, for example, is light-handed and rooted in the individualized perspectives of the characters, leaving room for ambiguity and contradiction. In one clip, Mariko speculates about the psychological motivations of her boyfriend and the men-in-his-category more broadly:

It’s interesting to note that Mariko is the product of a German father and a Japanese mother.

The implication, of course, is that she is reproducing the pattern of her own origin.

Now we can ask of the novel—are these sentiments true?

It’s not particularly worried about a conclusive answer.

The response within the text seems to be—who knows?

It’s not as if leftist men are uniquely attracted to Asian woman above-and-beyond their far right counterparts. At most, even if this hypothesis were to be true, it would simply be a complementary psychological explanation that sits alongside a mirror of its right-wing counterpart.7

The book doesn’t really care if this character’s theory is true or not: like reality, most psychological hypotheses in the domain of human motivation are not falsifiable with current technologies.

In effect, the novel poses these kinds of interesting questions, but swiftly moves on.

A novel that reads like a play (can be a good thing)

Like any story, The Sleepers is not without certain artistic liberties. The conceits of the book are marginal and, insofar as they sometimes seem to depart from a 1-to-1 realistic depiction of difficult human conversations, they’re stylistically acceptable externalizations of interior sentiments that you’d find in a compelling stage play.

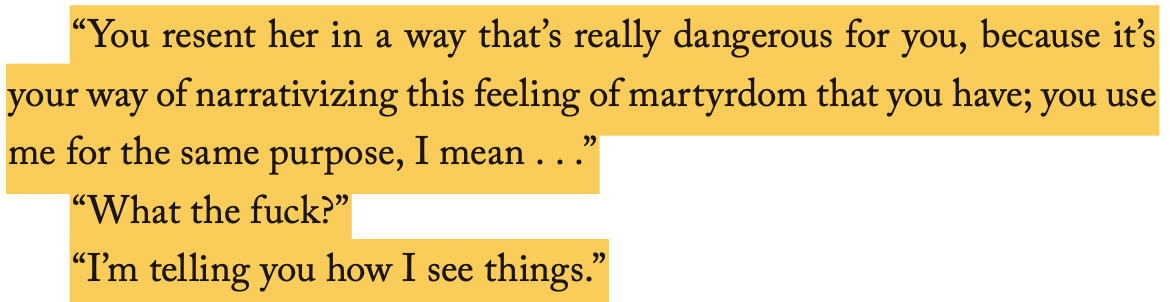

Dan, having an uncomfortable late-night conversation with Mariko, summons the combative interaction you’re more likely to find in a dialogue-driven performance:

The narrative arc of the novel hinges on Dan’s indiscretions and the multiplying consequences thereof—on the surface, it’s a classic sort-of “Me-too” style fall from grace, but the book spends little time moralizing about the ethics of power relations.

That is to say, it contains little in the way of arguments and more in the way of themes.

This—if I might be so presumptive, if I might engage in a bit of stolen-valor as part of a personal brand-building exercise—reads very /newwave/ to me.

Rather than advancing a sense of correctness, The Sleeprs presents a dispassionate mapping of the psychological drives that lead to the implosion of Dan’s life and the contributory actions from all of the parties involved.

In a sense, it feels like a novel written by a writer from an earlier era pulled forward into a semi-contemporary, ~2016-era setting.

Is Gasda an American Houellebecq?

Not quite, but the void of theism echoes throughout the book in musings like this:

Disenchantment isn’t merely downstream from digitization: it’s downstream from the death of God himself.

What is it that so resonated with this novel for me?

Quite simply, my feeling is that Gasda understands human beings very well.

Because he understands human beings very well, he writes very well.

A story doesn’t have to give you an answer

One of the things that works with the novel is the way that it engages with ambiguity.

That is not to say that it contains nothing in the way of moral epistemology—a sleazy, somewhat predatory film director (Xavier) is presented in a particularly negative light —but it presents this morality in gradations rather than binary classifications, i.e., with varying degrees of moral compromise.

The Sleepers presents notions of consent as complex and multifaceted psychological summations. The human being is an agent, yes, but one composed of various sub-agents with conflicting motivational drives. It’s not a nihilistic interpretation of sexual morality, merely a complicated one.

Further to that angle, what’s particularly interesting is that the “white men” in the book are essentially universally depicted uniformly negatively in their romantic with women of color. At the same time, Gasda has very little meta-commentary around that.

I have the feeling of a novelist looking to describe a certain-type-of-guy-and-how-he-might-be-perceived, a certain-type-of-horniness—a naturalistic account of a particular slice of a particular world.

A noticer, if you will.

New York City, the soul-crusher

Liberalism was supposed to be liberatory: to expand choice and, in doing so, to facilitate self-actualization.

But what if the subtraction of a narrow, social-prescribed choice-architecture merely regresses the problem of freedom to another level?

If a decision amounts to a biological computation, does that mean that freedom exists in the cranial determinism of the brain’s own internal reward circuitry?

Is that not merely a reformulation of the same problem?

What is agency, exactly, if human beings lack contra-causal free will?

But what did it all mean?

The Sleepers is a very sad book.

To the extent that it is sad, its sadness is a function of its presentation of the truth: a descriptive account of the genuine tragedy of an entire generation of failed millennial relationships.

Where are the answers, then?

We have not found them within us.

We don’t know where they are.

We don’t know.

Of course, this is not always the case, but it certainly can be. Think of No Longer Human or Stoner and works that have once again found a contemporary readership decades after their publishing.

I may have read this theory elsewhere and forgotten about it. Feel free to take credit if you think it’s yours.

Naomi Kanakia has estimated that there are perhaps only 10-20,000 regular readers of literary fiction. That number seems quite low to me, but I agree with this judgment in the directional sense.

For some good commentary on Dimes Square, I suggest reading Mo_Diggs and his piece on it here.

Just kidding about this one.

Consider the meme of the white nationalist bf and Japanese gf, and so on.

Good review! I just finished the book myself and I'm struck that you think Xavier is negatively portrayed. He's the only character who knows what he wants and who is able to be genuinely creative, in part no doubt because he's older than the millennials.

The main couple has potential but they suffer from a failure of desire that I think is supposed to be typical of their generation. Xavier knew what Mariko wanted and was pretty delicate about it, first having a relationship with her and then, moving on and drawing what the book assures us is a clear line, giving Mariko the most fulfilling roles of her career in small productions of Shakespeare and Chekov. In contrast, Dan doesn't know or at least won't acknowledge or act on either what Mariko wants (a family) or what Eliza wants (sex / the more impressive version of himself he presents in his lectures). This is partly because Dan the potentially interesting leftist intellectual who wrote about Henry James through the lens of Lukács has been diminished on every level by the internet, becoming a generic leftist blogger and a mediocre boyfriend. He sees his early potential reflected in Eliza, the student who is charmed by his lectures, but he can't even convincingly impersonate the man she wants him to be. Xavier, for his part, appreciates Mariko for exactly who she is. But Xavier is dying, and neither Dan nor Mariko can be creative in the way Xavier (and by implication his formed-before-the-internet generation) was.

(Gasda is a friendly acquaintance fwiw, discount as needed.)

Knowing yet gracious. And, fwiw, I agree. Well done!

I think you are right about the play quality, unsurprising given that Gasda is a playwright. I too noticed the long dialog stretches, and was a touch frustrated, but if you zoom out (as you suggest) they make sense. Gasda's conversations that go on too long, that cannot be left, trap the reader. Not exactly fun, but rather devastatingly effective. And I found myself losing patience with the whole scene, the whole generation?, the bullet . . .

Anyway, good book, and good review.