MY FIRST BOOK and Honor Levy's extremely online persona-based writer

reviewed from a place of neither hate nor love

I’m eleven. On Neopets I am God. I let my Blumaroo and my Xweetok and my Lutari and my Shoyru starve. I want to see if they will die.

Honor Levy writing in Internet Girl, a short story in My First Book.

I have a special qualification when it comes to Honor Levy and the discourse surrounding her—because I’m a complete non-entity in the world of traditional publishing, I have no strong feelings about her whatsoever.

Being professionally and geographically detached from the NYC literary scene and the people around it, writers like Levy are just interesting (albeit farway) contemporaries of mine. Some number of years ago, I vaguely remember that I would occasionally listen to her podcast, Wet Brain, which stood out not for its content but her obvious charisma which was evident even in auditory form.

So, it’s not as if I came into reading her book without understanding the persona of Honor Levy or her extremely adept ability to cultivate this, a feat which, if you know anything about book marketing (or even social media in general), sometimes seems like an attention lottery and sometimes seems like the product of a very intuitively sophisticated ability.

In literary spheres, my intuition is that this process of persona cultivation isn’t actually a primarily random phenomenon, and I like to pay attention when I notice a writer who can project their charisma out into the endless memescapes of the internet. I’m sure many people have strong feelings about her attention-to-skill ratio, but even though astute commentators like Alex Perez have pointed out that she seems to have had a great publicist backing her debut, even getting to the position of gathering enough literary attention for a publicist to care about your work in the first place is an extraordinarily difficult thing for a young writer to do.

I’d go beyond that, actually. It’s essentially functionally impossible.

To add to that, the other context here is that she is (or perhaps was) a part of the Dimes Square lit-scene. I can’t for the life of me remember the person who wrote this—I think maybe Christian Lorentzen mentioned it in a piece—but some literary critic asked the question (and I’m paraphrasing because I can’t find the source), “When it comes to Dimes Square, what’s the book? What’s the work that makes this whole scene matter?”1

For all the discourse around Dimes, which seems to have largely dissolved (along with the scene itself?), this has always been the central problem with it.

What’s the book? What’s the work of art that did or did not define this miniaturized attempt at a literary renaissance?

Levy’s book, for better or for worse, will likely always be considered the central book of the Dimes Square moment, even if it arrived toward the end of the scene’s lifespan (which is, in my view, has probably already naturally evolved into something less meme-y and more sustainable with the arrival of great literary mags like Noah Kumin’s The Mars Review of Books).

So—what’s the verdict?

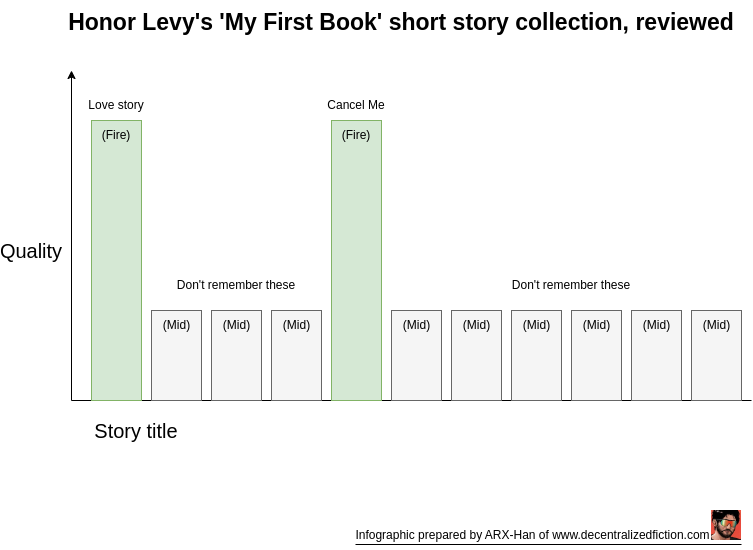

If you’re busy and just want the TL;Dr, I’ve drawn you a picture:

If I had to summarize my impression, I’d put it this way: I read and mostly enjoyed Honor Levy's short story collection. Like most persona-based writers (particularly those of the internet variety), it's one long exercise in a well cultivated voice. Does it work? Generally, yes, with one superbly funny story (Cancel Me, which was previously published online), with the rest being somewhere in the range of “okay-to-middling” and an almost exclusively persona-driven exercise in metafictional style (i.e. it’s like a slice-of-life anime, it’s plotless and directionless).

In addition to the standout Cancel Me, there's another excellent story, a piece of experimental fiction called Love Story that opens the collection and has proven to be very polarizing on Twitter, with people screenshotting its opening paragraph and sharing it with others.

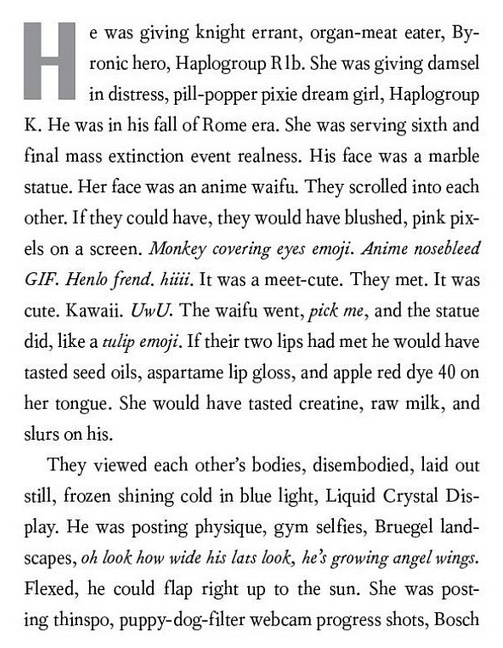

Let’s focus on Love Story, which, the more I think about it, is likely the piece that will be best remembered in the future (it will simultaneously also be the hardest to understand because of the dense web of contemporary internet culture references required to interpret it).

Here’s the first page, which almost invariably engenders a love/hate reaction:

This begs the underlying question—what’s good style?

The truth is you can only answer this question intuitively and from a base of having read a large volume of good prose. I can see why more traditionally-minded writers would find this an extremely repetitive implementation of the same trick over-and-over again, Hadouken-style, but my view is that Levy pulls it off (I’ll have more to say about repetition later on).

If you’re reading my blog, you know that I generally have few issues compartmentalizing aesthetic appreciation from the memetic content of a work of literary fiction. As such, I’ll segment out the moralistic critique of whether-or-not she’s “just-joking” or actually making an effort to aestheticize fascism (e.g. “She would have tasted creatine, raw milk, and slurs on his.”).2 The reason this piece works for me is because there’s a density of humor here that really does compound into a forward-momentum that charges the whole story with a kind of propulsive joie d’vivre, regardless of your politics:

She was posting thinspo, puppy-dog-filter webcam progress hsots, Bosch triptyches, wow you could put a whole stained-glass window in that thigh gap, the crucifixion maybe. Through her cathedral thigh gap you could see the sky where right-winged Icarus went flying by.

At the conclusion of the story, Levy also makes an effort to remind you that she’s not just doing-a-bit, dipping into Zoomer-sincerity:

Just before he hit send, it hit him, something sent from the beyond, a burning white light, a growing echo of music, the opening notes of MGMT’s “Little Dark Age.” And then it began: images flashing, hyperspeed through his mind, the Intertwined Lovers of Valdaro skeletons in their Neolithic tomb, huddles face-to-face with their arms and legs intertwined in an eternal embrace, Orpheus and Eurydice in the underworld, every pair of lovers ever intertwined in eteranl embrace, Odysseus and Penelope, Eloise and Abelard, Adam and Eve, Bella and Edward. At ever-accelerating nightcore speed, he saw nights and days, battles and births, blood, so much blood, beating hearts, cells dividing, code being written, oceans rising, blooming flowers, dying crops, the great flood, continental drift, the universe expanding, poetry, pain, the big bang, empires rising and falling, the birth of his ancestors, the death of his great-great-great-great-great-grandchildren, all of the ends and the beginnings beginning and ending and beginning and ending and beginning and ending infinitely. He saw Life is, and what Death signifies, and why Love is stronger than both. He saw a loop, a shining circle, He saw the way forward as he looked back.

I highlighted this segment because I very much enjoyed it and thought it was good writing.

So—My First Book is a short-story collection, roughly 10% of which is great.

What about the other ~90% of the book?

This, I’m less positive about. The reality is that almost all the stories are really just the same underlying story—autofictional humor about the ‘character’ of Honor Levy. Because the central core of the ‘character’ Honor Levy is her quirked-up Zoomer persona/look-at-me-look-how-funny-I-am type jokes repeated over-and-over again, the reader quickly starts to get the feeling that she doesn’t really have much to say and is sort of feeding you minor permutations of the same joke. Sometimes these land are quite funny but my main feeling when reading it was that it felt repetitive and at times a little bit tiresome.

And here we see the cul-de-sac of the autofictional movement in general: it’s retreat from consistent sincerity, its over-reliance on humor and demonstrations of cleverness, and (in Levy’s case) a kind of warmed-over mild throughline of “but don’t you guys think wokeness has gone too far?”

Here I have to emphasize that this is not, in my view, a genuinely subversive book: on the New Write podcast, James Pogue has pointed out that yes, there’s a Nick Land reference thrown in there (which I imagine the journalists at The Guardian would wokescold the editor for allowing in), but there is no substantive underlying white-identitarian ethnosupremacist animus that motivates her writing. Attempts to link her to that are spurious.

So we return to the core trick of the book, which is basically a celebration of a Unique and Interesting Voice of Her Generation, and fundamentally gets expressed through an increasingly tiresome repetition-of-the-same-cleverness. This instinct toward repetition may also be why I noted a couple instances of anaphora that had been quite clearly overused—a trick that I’d always associated with millennial writers who leaned too hard into mimimalism-as-an-affectation, and one which personally took me years to outgrow (maybe the Zoomers and us millennials aren’t so different, after all!).

Nonetheless, there were a small number of moments of sincerity which stuck out, like this one:

She wants to wake up her parents and ask what they have made besides her, but she lets them sleep because she already knows what they will say. They will tell her that she is the greatest thing that they ever made. She will know that she is not all that great, but compared to the money and those good investments and her mom’s crochet animals and her dad’s straight-to-video movies, it’s true, she is the greatest thing her parents ever made. If she woke them up, they’d ask why she smells like cigarettes and if she wants to get lunch cancer and if she thinks she’s invincible or that smoking makes her interesting. She would tell them, like them, she is dust and will return to dust. The question is what will remain.

The short story Written by sad girl in the third person, by Honor Levy, in My First book.

Levy is clearly a talented writer, and even if you hate Love Story, the satirical Cancel Me absolutely does soar to great heights and shows her at her best (rarely do I laugh out loud when reading a short story). The number of early twenty-somethings who could write a story that funny and cutting is no doubt exceedingly small, but my intuition is that she may struggle to write a more fulsome, sincere novel that Actually-Has-Something-To-Say. I am hopeful that she will do so in the future (because the world always benefits from receiving good works of literature), but the incentive structure of persona-based writing may be a structural limiter in this regard. To the extent that I’m being a bit harsh on her, I share the sentiment of Valerie Stivers, who wrote a great review in Compact Mag which took a similar line in feeling that many of the stories seemed under-cooked but there were nonetheless various standout moments.

If I had to guess, I would surmise that Levy’s incentives, likely created by her publisher, were to funnel her into performing the clever character of herself on a page and to push the book out now, while her level-of-attention still ran hot.

Given the brutal economics of the publishing industry (even for literary it girls), I’m actually completely fine with that, and while many writers will choose to debut with more polished works, I don’t think that a mixed debut like this is likely to be a career mistake. If anything, will likely set her up for a more substantive novel down the line—if she ever gets around to writing it.

A reader has suggested that this quote may belong to Jack Antonoff.

I’m sure some would make the same critique of my similarly satirical novel, INCEL, even though it arguably has a clearer moral valence in this regard, and I’m not particularly interested in levying accusations.

All short story collections should have a graph like this. Very helpful.

I read "Love Story" and "Cancel Me" to see what all the fuss was about. I don't see what all the fuss is about.