First Things first: an INCEL thinkpiece appears in First Things magazine

Shilling your way into literary credibility from the Amazon KDP gutter

I think for a certain type of literary purist, shilling your work feels incredibly crass. When you grow up reading stories about how Cormac McCarthy was so poor that he kept a light-bulb with him to read deep into the night inside a string of cheap motels, this kind of aesthetic asceticism contains a certain kind of sense to it. It’s the thing you see portrayed in various mythology-building Hollywood literary biopics: the shining path of the single-minded artist unwilling to do anything other than the art itself.

I have great respect for people who have the capacity to struggle like this.

This focus on purity is not altogether without context—in an era of unlimited vanity, even a little bit of self-promotion can start to feel like a form of self-excess because of the gravitational pull of audience capture and algorithmic reward, factors which weren’t present in earlier eras of micro-celebrity. More generally, I’m certain that traditional forms of literary careerism are soul-crushing for most of the participants in the traditional ecosystem.

I have never thought this way, because for me, book marketing is a game.

I am spiritually and culturally American. I have been playing games my entire. I love games!

Further to that, I’m a nobody—a pseudanon on the internet—with no agent, no literary press, and no institutional backing.1

The underlying problem for the purist is that literary writing and book marketing are essentially orthogonal skillsets. It’s hard to do things that are decorrelated skillsets. But! If you look at history, I think it’s surprisingly easy to accidentally retcon the peak wordcel-era (the back half of the 20th century notable novelists) as an era of greater literary purism.

With the benefit of hindsight, I think many of us have an unconscious bias where we conceptualize famous novelists as people who were just organically “living their lives” rather than, on some level, deliberately cultivating literary personas in a less technologically sophisticated era of mass media distribution.

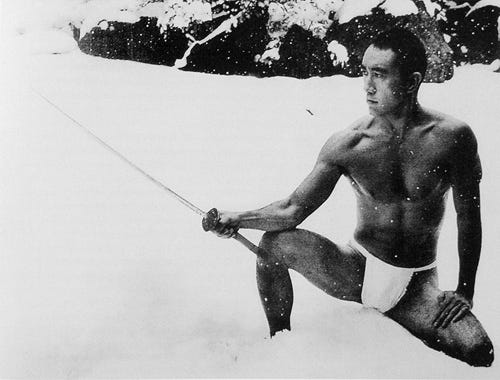

For example, here’s a photo of Yukio Mishima just hanging out and doing nothing in particular:

Time has rendered this picture of Mishima into something more serious than it really is, I think. What we have here, frankly, is an influencer photoshoot. Mishima loved doing this. He absolutely loved doing fabulous literary influencer cosplay photoshoots. If anything, I am jealous of his aura. The man was prodigious, producing a voluminous amount of work, and still found the time to cultivate a form of self-serious literary celebrity.

Granted, Mishima didn’t need to do this kind of persona-building in order to drive his novel-sales.

But it didn’t hurt, did it?

It’s 2025, WW3 is about to start, and we’re still here talking about him, aren’t we?

Making it in America (for wordcels)

One of my favorite narrative structures is the “making it in America”-type story. I loved How To Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia by Mohsin Hamid, and I also very much enjoyed Flesh by David Szalay, which recently came out this year.

Perhaps this is because I am an immigrant, and perhaps this is because is because I love the idea of climbing, but these types of striver stories have always appealed to me.

What’s fun about striving to becoming a successful, renowned novelist in America is that it’s like striving to become a successful and renowned cellist or Magic: The Gathering card player—absolutely no one gives a shit.

There’s a beautiful freedom in the bar being so low.

Some thoughts on the First Things thinkpiece about INCEL

First things first, I’m grateful to Scott Litts for putting in the work to write a compelling analysis of my novel, INCEL. It’s a significant personal milestone for me as a writer and will help to draw out the long tail for the novel as it approaches 1,000 copies sold (I’m ~75% of the way there!).

For me, I have to situate Scott’s review behind my own motivation for writing the novel, which I always viewed as largely a philosophical type of story.

Let me explain.

One of the things that has repeatedly frustrated me about (some) modern literary fiction is how thin the thematic layer feels. That’s not to say a novel necessarily has to explore some critical load-bearing philosophical concept, only that the lack of interest in engaging with these topics sometimes feels like it’s secondary to a more general sparsity of the author’s world-model and general lack of depth.

The general critique of contemporary novelists working right now is that they are often overly focused on hyper-contemporary political issues to the exclusion of other equally but less interesting topics. This creates a kind of “time-decay” effect where the books get historically pinned to, say, specific conditions under the Obama era, in a way that rapidly depreciates how interesting the story is in retrospect.

To give but one recent example, I enjoyed Yaa Gyasi’s Transcendent Kingdom, a book about an African doctoral researcher working set in the context of her religious Christian upbringing.

A concept like this is an incredibly rich vein of philosophical exploration: you could, for example, closely track the protagonist’s fall from faith and how this psychological journey is intertwined with actually impactful metaphysics around, say, the problem of suffering, or the epistemological problems with faith as an argument for theism in general.

Instead, you don’t really get much of that, and the narrative lens zooms in very close to a much less interesting story about her brother’s opiate addiction problems. It felt to me that it never substantively expanded into a wider aperture around faith, religion, and meaning.

I think I understand why. Modern realist style is averse to anything other than capturing moment-to-moment verisimilitude, but its definition of verisimilitude evades psychological accounts of religious, metaphysical, or philosophical viewpoint changes.

It’s hard to dramatize an internal intellectual conflict without it being boring!

In hindsight this makes perfect sense: the reason it’s hard to write a philosophical novel because the novel is, by default, not the optimum vehicle for philosophy (that would be the essay!).2 The default failure mode of the philosophical novel is a descent into long back-and-forth dialetical arguments between characters acting as mouthpieces for paragraph blocks that belong in an essay or an academic paper.3

With INCEL, I wanted to focus my critique on scientism through the lens of ideological capture on the internet and what this feels like on the inside rather than as a set of propositional arguments.

It’s no secret that gender discourse has driven everyone completely insane in the past 15-odd years, and modern inceldom is merely a subset of this more general problem.

But fascinatingly, these problems are upstream of scientific and philosophical developments—Darwinism, materialism, scientism, and reductionism—that arguably began hundreds of years ago.

What feels hyperlocal to the internet age actually has a long lineage.

Enter Litts

Scott Litts is a writer, filmmaker, and critic with a varied body of work that you can find here on his website (you can check out some his experimental films here).

The worldview explored in Incel is a crystallization of what Jean Baudrillard terms “obscenity” in his 1979 work Seduction.4 The obscene, for Baudrillard, is less about explicitness than an excess of rational clarity, a stripping away of mystery and ambiguity until all that remains is the brute, predictable fact of material reality. In an obscene culture, “Everything is to be produced, everything is to be legible, everything is to become real, visible, accountable; everything is to be transcribed in relations of force, systems of concepts or measurable energy.” Obscenity is a fixation on quantifiable certainty and total disclosure.

Obscenity stands in opposition to Baudrillard’s twin concept of seduction. Seduction derives its charm from uncertainty and secrecy. It is the levity and frivolity of fun, as opposed to the stern purpose of work. Seduction is largely defined by what is omitted, unknown, unknowable. It resists, above all else, explicit definition.

Here Litts frames the intense scientific reductionism of anon in the novel as a form of Baudrillardian obscenity: romantic relationships are something to metricised, and this quantification reduces the organic to the obscene.

There’s (understandably) a lot of hand-wringing about “modernity” in various social and cultural thinkpieces, but the reason I think the modern incel is so significant is because he (or she) is a harbinger of what is to come.

What is to come, you say?

I think, essentially, a terminal unraveling of human meaning driven by immersive AI-powered products and services. Markets—in the form of technocapital acceleration and dopamine capitalism—are a sort of path-finding algorithm. They exist to connect the shortest possible distance between desire and reward, and in collapsing that distance, they erase the struggle of striving toward goals in general that we are evolved to endure.

This manifests as a form of radical and escalating disempowerment and short-circuiting of goal-seeking behavior whereby people experience a collapse in personal agency and drop out of whatever agentic games they would otherwise find meaning in (work, romantic relationships, and so on).

The Japanese Hikkikomori was, we now know, merely the East Asian precursor analog to the American incel. Japan, being at the forefront of modernity and dopamine capitalism, simply hit the perimeter of social breakdown first.

I think people don’t understand how rapidly this trend is going to accelerate and how economically redundant most of us are about to become because quantification isn’t going away anytime soon (it’s getting worse). Scott’s review taps into this mega-trend.

How to shill your way into a credible literary magazine

Occasionally, I have people who notice my (very modest) level of niche traction and ask me for a couple of pointers.

While I’m certainly grateful to be featured in First Things, the truth is I don’t have any special insight into book marketing. There are many self-published writers who are far superior when it comes to achieving book sales. To cite but one of many examples, I could cite dozens of writers who write Werewolf-fuck-fantasies who are orders of magnitude better at book marketing than I am.

But of course, writing genre fiction is a different game, so I’m being somewhat facetious here. We all know that literary fiction is its own tiny sphere of niche competition. That is to say that marketing literary erotica is different than marketing (the much more niche) literary fiction category.

My strategy consists of three components:

Consistently blogging and micro-blogging (via Notes) on Substack, which is now the most important social network for writers.

Cultivating friendly relationships with other writers online via DM’s on Substack and X, including appearing on their podcasts (this is how I met Scott).

If I could, I’d consistently go to literary parties in NYC to amplify this effect, but I can’t because I don’t live there and am almost never in town.

Putting effort into online authorial visual design (e.g. my PfP), branding (consistent visual design elements across social media profiles), and especially the book cover (book covers are hugely important and you should invest a lot into making them good). I think a lot of people neglect this aspect. I like the design aspect and have a lot of fun with it.

That’s it.

Being “taken seriously” in the literary-criticism sense is a function of (1) the type of work you’re outputting and (2), your reach/eyeball-exposure, the latter of which is merely a funnel for the actual work itself.

Beyond that, critical exposure has a natural kind of compounding effect: each review begets additional reviews, and more prominent reviews tend to beget more prominent reviews and so on. Starting this virtuous compounding cycle is difficult but doable if you just keep churning new stuff out.

As a writer, you have no control over this other than writing the best stuff you can.

The reason that this strategy outlined above is not 1-to-1 reproducible is because its success is contingent on the specific execution of all of the above multiplied by some large factor of randomness. I happen to have more readers on this blog than I ever anticipated gathering largely because the Substack algorithm favored some random piece I wrote about the lack of interesting Asian-American cultural production.

I don’t perfectly remember how I first met Scott online, but it was over Twitter (we have some overlapping e-friends and travel in partially overlapping circles online). We shared a common interest in Dan Baltic’s excellent Nutcrankr and I offered him a free copy of my book. Some months later he read it and told me he was working on an article because he liked the philosophical content in the novel. Later, he finished it, and recently, it got published.

Note that this sequence of events was almost entirely out of my control: it’s almost wholly a function of Scott’s established pedigree and general stature in the NYC literary community (previously, he’s also helped publish an Expat novel.

While I think Twitter is largely useless for promotion, I think it’s still useful for meeting other writers. Just being active and putting out stuff will eventually gain you attention, and people who like your stuff will eventually find you.

That’s it.

That’s the whole playbook!

Aura-farming your way to success

As a closing thought, I think that one of the underrated factors that explains book marketing success is the charisma of the novelist themselves. This amplifies the effect of everything else as a kind of success multiplier. A lot of people complain about literary nepo-babies (sometimes deservedly) but my personal theory is that charisma is more often the core success differentiator, even among people who are well connected.

Now, for myself—pseudonymous, anime-avatar, voice-changer—it’s not really possible to convey any sort of corporeal charisma. The most I can do is put effort into the visual design and branding of my online avatar.

Maybe it’s because I recently took a trip to Japan, but lately, I’ve been impressed by a lot of Japanese artistry and cultural production—and in particular, the presence that some of their artists are able to convey.

This clip below recently went viral, and illustrates my point:5

Where does this charisma come from?

I think, in its purest form, it stems from a lack of self-consciousness. Last month I spent some time in Tokyo and Osaka, and (as always) it was interesting to contrast the native population’s body language to that of my generation of Asian-Americans. The difference in self-consciousness between these two groups couldn’t be more extreme. I felt like I was in another universe.

If we scope in on the literary implementation of charisma, I think it’s ultimately less about consciously cultivating a certain persona (which feels fake, like DFW) than it is about unconsciously capturing a certain form of energy that I think matters most.

Think back to the Mishima photoshoot from earlier in this post. There’s an incredible intensity to him that runs deeper than the obvious performative layer. That’s what I mean by energy in this case.

It’s a form of artistic energy, a stream of life that you channel moreso than generate de novo. It’s the thing-that-is-not-reducible that is perhaps the most important thing, because literary capabilities aside, it’s the thrust that makes a writer’s work interesting, and interesting work always has an easier time gaining distribution. These things then manifest in the literary work itself and in the author’s IRL-presence.

When I survey the landscape of Asian-American novelists, my feeling is less that something is technically missing—for example, in terms of their prose-level skillset—and more that something is energetically missing. Mishima had it. (Maybe) Murakami had it (for a period of time, before he started repeating himself).

The Japanese had the sauce and there is no denying it.

Who’s going to get it next?

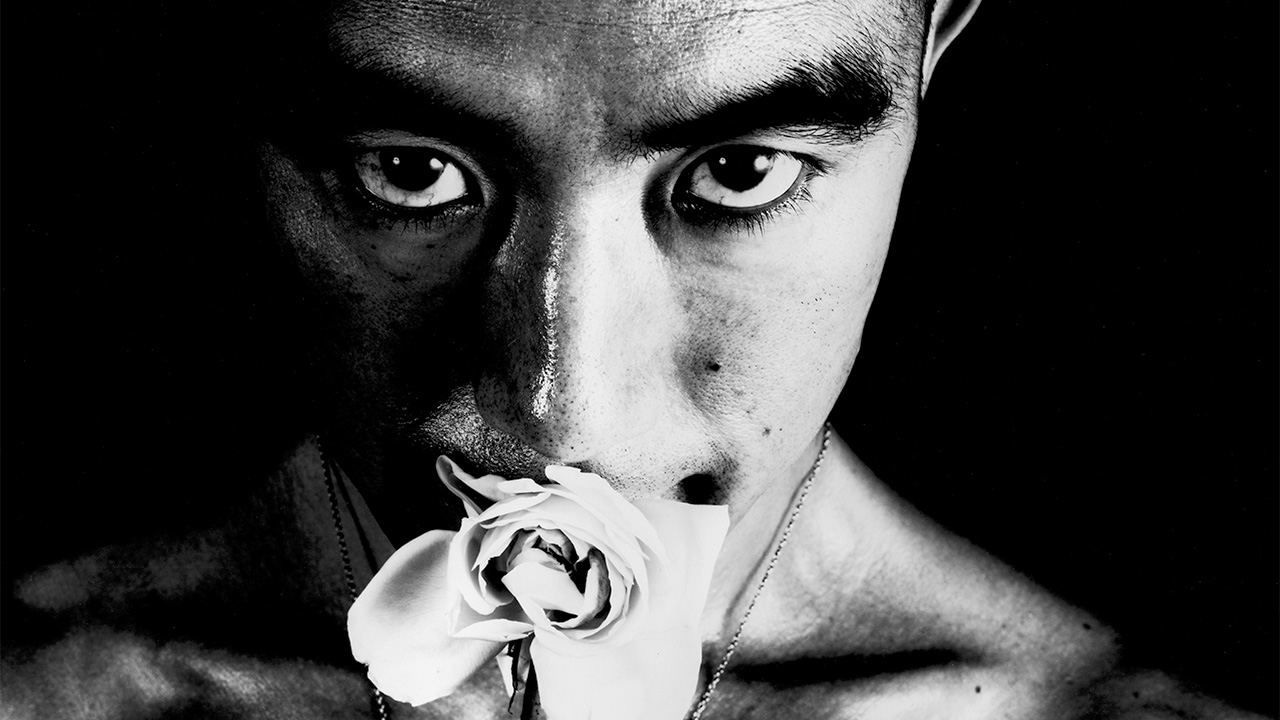

Regardless of the corporeal limiter, a pseudonymous writer should still do what they can in this category. Maybe digital avatars will progress enough that persona cultivation becomes more possible. Lately, I’ve been playing around with updating my authorial avatar to add another boost to my profile on Substack. I recently combined some generative art with a new character design and some simple Japanese-style J-Pop album art with Chinese lettering.

I’m out here having fun with it!

Coda: Buy my novel (and rate it also!)

If you enjoyed this post, I’d ask you check out my debut novel, INCEL, which was originally published in 2023, but remains as topical as ever.

(Also, for those of you who have read the book, adding a rating or review on Amazon or Goodreads helps me a lot).

Thanks!

I have online e-friends who are writers. This, to me, is better than most “institutional” backing at this point.

For a particularly bad example, read a copy of R. Scott Bakker’s Neuropath.

I guess sometimes this can work at least on a commercial level—Ayn Rand, for example.

I once read Simulacra and Simulation and understood perhaps five percent of it (continental French theorists like Baudrillard ares the final boss of wordcels).

Cultivated literary personas are nothing new. I can't find the article, but I once read how Kurt Vonnegut basically completely remade his personality and appearance to sell his books.

Great piece. A "thin thematic layer" is a great way of putting how oddly empty so much of contemporary literature sometimes seems. It's so frustrating to start a book with a rich premise and then end up on a rigid guided tour of the least interesting parts.