Decentralized Fiction and the inherent tradeoff between censorship-resistance and distribution

Expat Press, New Ritual Press, and the question of inherent tradeoffs for the outsider artist

I recently had a very interesting conversation with the Bitcoin OG Jimmy Song about censorship resistance, and felt compelled to draw up a new framework that I hope will be useful for other outsider novelists like me.

See, the funnest part of being a literary theorist is the world-building aspect. Of course, I’m using the term world-building in a tongue-in-cheek sense, since I am ultimately trying to correctly model the world on this blog—not merely trying to create some towering complex of verbal and conceptual abstractions.1

If an idea is sufficiently entertaining, it tends to be generative—i.e., people will debate “what the thing actually means.”

Let’s unpack, then, how the idea of decentralized fiction might be variously construed:

First definition: The Press as the centralizer/decentralizer

Fiction that is produced outside of large, centralized, corporate conglomerates (“the big five”)2, and is instead produced by small indie-publishers or self-published works.

Typically, we’ve called this “indie-lit” or “alt-lit.” Smaller publishers like Expat Press or Serpent Club Press.

Second definition: Cultural aesthetics as the centralizer/decentralizer

This model shifts the definition of centralization away from institutional centralization to ideological centralization.

Under this model, decentralized fiction is any work that escapes the functionally-centralized trend toward cultural homogeneity that is present in the space of literary fiction as a whole—regardless of whether the novel is published by Simon and Shuster vs. your typical indie press.

This implies a “Cathedral”-like critique of cultural production in the West: if the vast majority of indie presses are maximally leading-edge progressive in their cultural aesthetics, then they do not represent a meaningful deviation from work that would be operating under similar constraints under traditional publishing.

Note that this does not necessarily require an indie-press to be right-wing, but right-wing presses would definitionally be included in this category merely because they’re countercultural in the literary space (even if they’re now presently aligned with the reins of political power in the Trumpian sense). Here I’d be thinking of something like Passage Press as a notable example.3 Another key example would be New Ritual Press, which, despite being labelled as “anti-woke” by the Rolling Stone editor who titled the recent magazine article about them, does not appear to be meaningfully engaged in politics at all.

Third definition: Authorial identity as the centralizer/decentralizer

In a PvP-world, a name is no longer a mere signifier, it’s a central attack surface. It has always been the case that writing can get you into trouble, and I want to paraphrase a great tweet recently about how writing has asymmetric downside—roughly, “it’s easy to get in some degree of trouble from your writing, but it’s very hard to become the next JK Rowling.”4 A name is a database-centralizer that makes you more legible to a variety of people, including unstable, angry ones—and most concerningly, the state itself.

We are increasingly in a world where Western states, regardless of their leftist or rightist orientation, will severely punish speech. This is the unambiguous trendline and we’ve seen it from Democratic administrations, the Trump administration, European technocrats, European rightists, etc.

There are varying levels of OPSEC you can deploy here—I originally wildly overcorrected for this (no one will ever care that I exist, and I mean that in a good way), but Zero HP Lovecraft would be an example of someone who is writing outsider fiction at the highest-level and remains highly disciplined with his pseudonymity (e.g. not even publishing on AMAZORG, which actually can be done 100% pseudonymously—it just takes a lot of effort).

Pseudonymity/facelessness is a form of emancipation: it simply allows you to speak more freely.

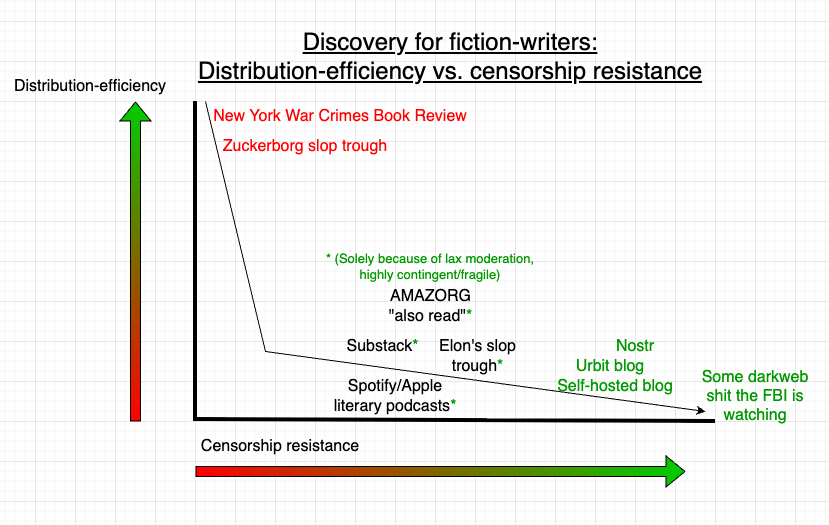

Fourth definition: Discovery & Distribution as the centralizer/decentralizer

This model focused on how books are marketed and sold. Fiction that is discovered and distributed in a censorship-resistant fashion is, in my view, the most important axis of decentralization, simply because censorship-resistance is what most effectively promotes freedom of speech.

An extremely important caveat: centralized platforms may have relatively minimal moderation, which functionally enables an indirect form of decentralization (weird, right?). To give but one example, the pseudonymous outsider writer Delicious Tacos made his career publishing Carver-esque short stories about nihilistic modern sex on the #1 Megacorporate-Werewolf-Fuck-Fantasy reading-platform in the world (AMAZORG).

I’d note further that, undergirding all of this is effectively the First Amendment and the decentralized internet itself, without which we would all be horribly lost (and both of which are currently under active, multi-domain assault by a variety of domestic actors).5

The thing that I want to impart here is a very simple framing: every novelist must choose what constitutes an acceptable tradeoff between censorship-resistance and distribution.

Let’s look at some interesting examples of how fiction is discovered and distributed in a censorship-resistant or non-censorship resistant fashion.

Discovering fiction writers: Censorship-resistance vs. Distribution

The reality is that almost no indie fiction is discovered at any meaningful degree of scale via purely decentralized, censorship resistant platforms.

In 2023, I tried to promote my novel on Urbit after hearing Justin Murphy promote it on his podcast for years. I came to discover that Urbit was a horribly broken, shitty Discord replacement with a small number of interesting people on it (it also used to have very a beautiful landing page, but that too is now gone). The result was that I was able to give away a handful of digital copies of my novel and make contact with a couple of people who I was able to reach on other platforms anyway.

I admire the ethos behind a project like Urbit, but executing a project like this is enormously difficult. Jimmy Song mentioned a platform like Nostr, which I’d only ever passingly heard of, but it’s a great example of the challenge here:

Distributed, censorship resistant social networks could in theory be used for discovery of new works of literary fiction.

Because they typically require more technical sophistication from users, they are high-friction and fail to capture network effects.

This means that no one goes on these sites, and you can’t promote your novels there.

Well, what about a self-hosted blog? The old classic!

A self-hosted blog is, in general, good, but the discovery of blogs typically regresses to people linking to your blog on various social media platforms, which are themselves centralized platforms. This is because the independent blogosphere, which consisted of extensive cross-linking, is basically dead now (and may it Rest in Peace—Katherine Dee has written eloquently about this).

Even Nick Land is mostly just active on Twitter and the occasional podcast, the latter of which is distributed on giant centralized platforms like Spotify anyhow!

What about the bird site?

Well, Twitter, as we all know, has been murdered for new writers courtesy of enshittification, account-throttling and link-punishment courtesy of Slop-King Elon.6

The most interesting platforms here are really Substack itself and a loose affiliation of literary podcasts, and only because the moderation on these platforms is currently very minimal. The essential advantage of Substack is the network effects from the built-in discovery function of Substack notes, recommendations, tagging other writers, etc.

Indirectly, almost all my success is attributable to this website. Ross Barkan is right to point out its increasing significance in literary fiction.

Regardless, I remain fearful of what will happen when content moderation becomes algorithmically smarter and you can easily scale ideological policing of text with near-perfect accuracy. “We can’t practically do this” is a great excuse for platforms to have when they’re put under pressure and remains a high-friction barrier to implementing state-driven or NGO-driven speech repression.

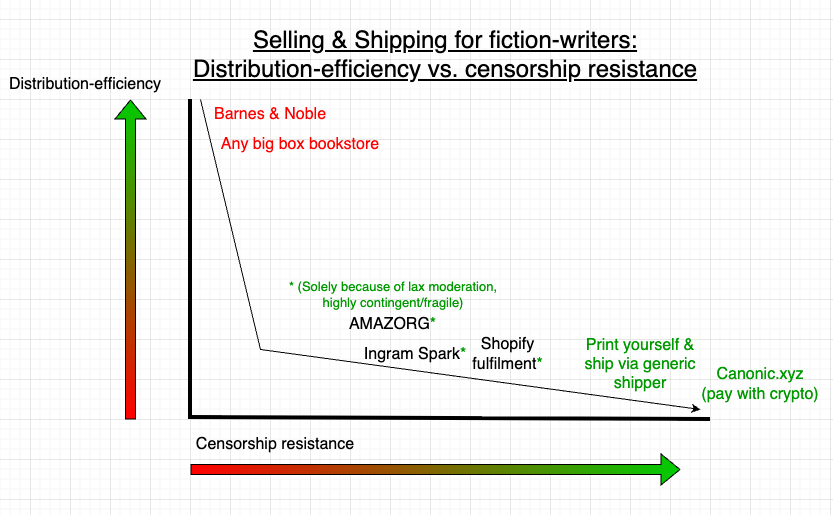

Selling and shipping literary fiction: Censorship-resistance vs. Distribution

The elephant in the room is AMAZORG.

For all its faults, AMAZORG, due to its best-in-class logistics/Rube-Goldberg-human-suffering-delivery-fulfilment-pain-distribution system, has arguably enabled a renaissance in indie literature.

Because it’s not cost-effective to aggressively content-police the enormous volume of self-published books sold on their platform above and beyond the absolutely bare minimum level, content moderation on the platform is quite restrained.

Coupled with self-publishing as an option, this functionally enables outsider literature to flourish, particularly when someone applies artisanal effort (and non-trivial budget) to the book design & packaging (here, someone like myself or Alex Muka come to mind).

The problem, of course, is we simply don’t know how long this will last.

Consider alternatives like Expat Press, which do not appear to sell on AMAZORG:

I admire and respect the work of people like Manuel who, as I understand it, print and ship all their own novels with no MNC-intermediary. There’s a real artisanal craftsmanship aspect to this that I sincerely hope continues. It also allows them to print and craft the books to their own specifications and retain greater control over shipping & distribution relative to handing that power over to AMAZORG.

The problem, of course, is the friction in buying.

If someone buys a book on Amazon, even if it’s POD, it arrives very quickly and they can often buy it with a single-click or two. More importantly, readers get into the habit of buying books and everything else off of Amazon online, which even further decreases the cognitive friction of buying.

With many other online retailers, entering in your checkout information adds just enough friction that the efficiency of distribution and ease of purchasing the book dramatically reduces sales. Many book purchases occur at the psychological margin, moments after someone discovers a new writer, and impulsiveness and ease-of-buying are net-good features for the experience of the shopper.

It’s a huge problem that’s more or less inherent to human psychology.

An indie press like New Ritual Press has gone the conventional route: distributing on AMAZORG:

Now, there’s nothing wrong with this strategy, but I worry about the hammer coming down on all of us one day. It’s hard to predict, politically, when that might happen, as it would appear to be a function of how much closer the United States ratchets toward a more authoritarian instance of red or blue control.

Lastly, there is a third-way between these two poles, a compromise approach: printing your own books and shipping them, but releasing digital-only books on AMAZORG (I’ve seen Passage Press do this for some books). It remains to be seen if this is a viable strategy or not.

Even more confusingly, censorship can happen at the level of both printers, shippers, and payment processors, which further complicates the process of distribution.

For most of you

For most outsider artists, I’d recommend the following distribution stack:

Substack, even though it’s centralized, due to lax moderation, for discovery. In parallel, considering mirroring your blog to your own authorial website. Regularly export your e-mail list of subscribers for when the platform (eventually) becomes enshittified in xyz years.

AMAZORG, for all its faults, for publishing. Consider also Ingram Spark, Apple Books, etc., if you’re so inclined, but only if you don’t mind the extra effort for much more marginal return. Keep the publication files forever and don’t lose them.

Lastly, regarding pseudonymity:

This is largely a function of personal preference, risk-tolerance, and general DGAF-points. Facedoxx if you want to enjoy the NYC literary scene and can’t functionally be fired or don’t care if you lose your job. Pseudonymity if you’re a normie and just don’t want to deal with even the minor headaches of being a public-facing person with even a small amount of successful traction. In many cases pseudonymity won’t be necessary and is complete overkill (e.g. mine). Remember that it’s a spectrum, and know that here’s a tradeoff between facedoxxing & establishing yourself online vs. being “harder-to-remember” and pseudonymous—I can’t do video podcasts, for example, which would be really fun.

If you meaningfully touch on anything political and live/work in the US (I’m not in this category), you should work in some margin of error to account for the fact that the US is trending toward increasing levels of civil conflict and internal political repression. Unless you’re specifically an immigrant writing about Palestine and the lobby is putting your name on a targeting list that is going directly to the op of the Trump administration, risk here remains low because notoriety is required for the eye of Sauron to turn on you. That said, it does feel like the general climate is turning for the worse, and it remains possible that relatively anodyne writers will one day be ruthlessly targeted by whoever is in power anyway (whether red or blue, you can’t hide from Palantir, etc.).7

You’ll have to leave that to European continental philosophers and S-tier parasocial wordcel intellectuals. Right now, I can’t afford the Oliver-Peoples glasses required for that.

Famously, Dan Sinykin has written about this: see Naomi Kanakia’s excellent review of Big Fiction here.

Note that this isn’t a perfect categorization since it seems that Passage is primarily focused on political writing and less focused on releasing original novels. It’ll be interesting to see what kind of novels they end up putting out and I’ll be watching this space closely.

I believe it was the excellent Marko Jukić of the Bismarck Brief but I can’t find the tweet.

See this excellent Palladium Editors piece: “The Centralized Internet is Inevitable.”

I’m still horribly addicted to the site anyway, lol.

Ideally, like me, you live on a Southeast Asian beach and run your own business dropshipping custom teledildonics to German sex-autists from a chain-smoking Shenzhen factory-owner you met at a rave this one time.

I never even considered trying to find a real publisher. We live in the age of the Internet, where anyone can publish anything they want for the cost of a server, so that's what I did. (I got a dedicated machine from ARP networks. It kicks butt).

People don't seem to know what to make of this. You just put your novel on a website? You"re not on Amazon or Kindle? You don't have an ISBN? I once asked for promotion advice on a Reddit sub dedicated to self-publishing -- I got crickets.

This is a practical overview of the risks, rewards, and realities here. Thanks for articulating it all so concisely.