David Herod's 'Improvidence' & revisiting the definition of literary decentralization

reviewing a post-apocalyptic novella & thinking about how centralized vs. decentralized cultural production

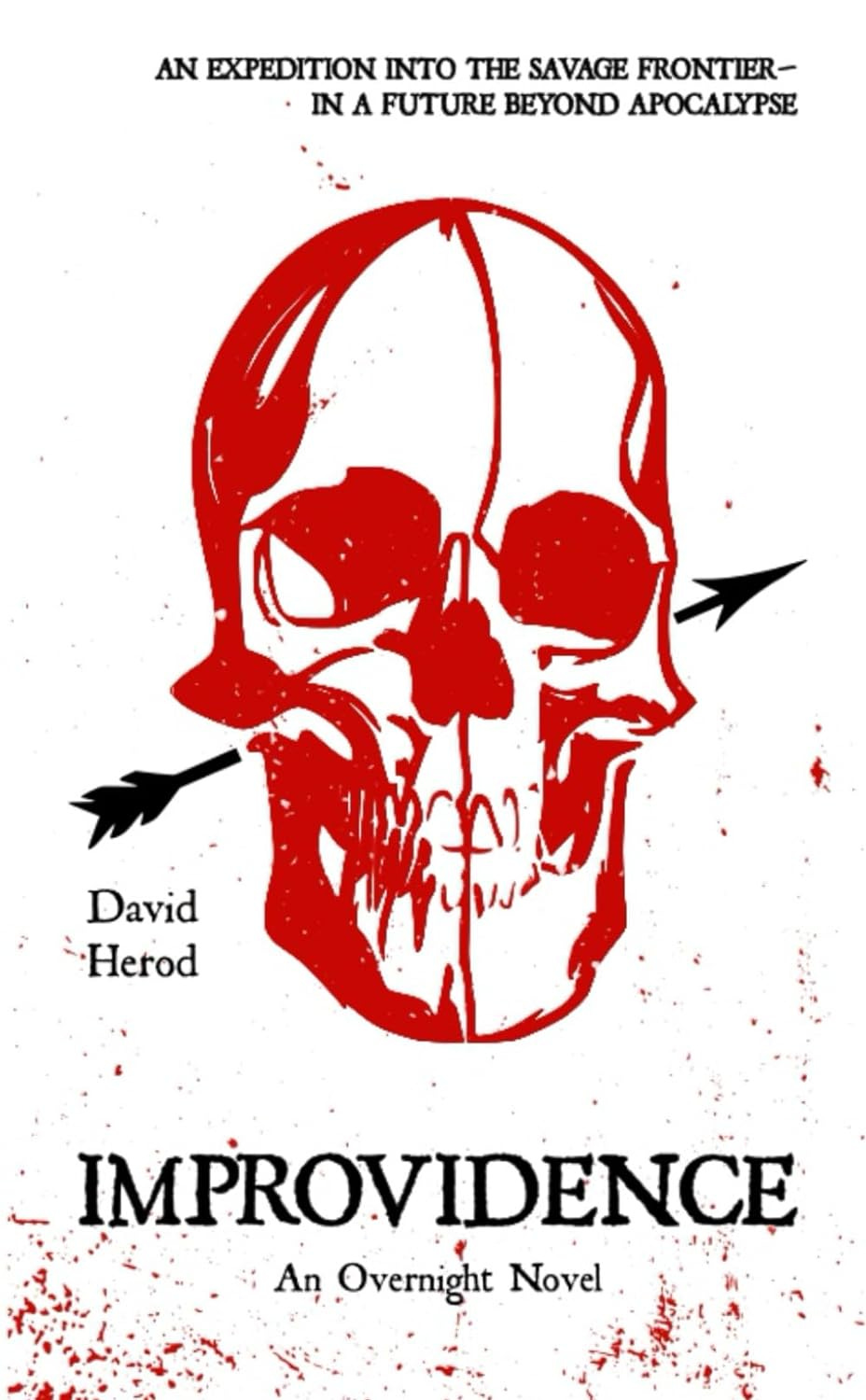

David Herod of Tooky's Mag has written a short post-apocalyptic novella, Improvidence, which I enjoyed over the course of several spare moments accumulated over the past several weeks.

The story clocks in at a spare 86 pages, but feels longer because of its attention to worldbuilding detail, surprisingly-high (for its genre) level of prose, and the tightly-crafted structure of Herod’s storytelling abilities. It has a surprising level of density for such a short book and feeling of being more weighty than its spine would sugest.

While I don’t read much genre, I found the book to be a good, enjoyable read, and its positive qualities also serve as a jumping off point for a broader discussion about centralizing dynamics and decentralizing dynamics in the production of literature and culture more broadly.

Executing a good genre piece is, in my view, actually a very difficult thing to do well for a number of reasons. Worldbuilding is deceptively difficult and also easy to over-index on: writers become enamored with building mind-palaces of complex magic systems, lore, and so on, something akin to a programmer fixating on method over and above final product.

In this regard, Herod avoids this trap rather deftfully:

Jeremy had been leading me off-road, down a ravine to circumnavigate a ruined bridge, when my ears perked up to a hollow rattling sound that trailed the wind’s keen. So we drew our reins and pursued it down the ravine, startling off a migratory flock of magpies who screamed into the sky and left behind a yawning hollow of earth like an aborted canyon, large enough to fit the governor’s fort with room to spare. We were surrounded on three sides by sheer walls of dyed red earth that cascaded with long trails of ancient plastic that waved stiffly in the breeze. About the hollow’s floor several dozen bottles of plastic and aluminum rattled in each passing gale, spiraling fruitlessly about the riverbed of erosion.

“Dear God,” whispered Jeremy beside me, “it’s a fortune.”

There’s a couple of things happening here that are interesting:

Herod is quite adept at descriptive prose, particularly of nature (and in this case, post-civilizational refuse). Good descriptions of natural beauty are subtly difficult passages to execute, and Herod has the skill for it. Maybe because most of the writers I read are so urban (with the exception of the occasional McCarthy book), I found this refreshing.

The punchline of the plastic refuse being economically valuable in a post-apocalyptic setting is funny, and a great example of minimally intrusive, thoughtful worldbuilding that isn’t reliant on classical exposition.

The character’s voice leans into an interesting historical retrogression: Herod imagines a future where apocalypse has reverted the cognition and language of men into a simulacrum of an earlier period (roughly the 1800’s, perhaps). This is another good stylistic choice that also obliquely integrates another layer of worldbuilding: the people of this era are not like us; they think (and speak!) differently.

Without spoiling the ending of the story, I’d say that the novella doesn’t overtly engage in any kind of overtly-politically-coded theme or message, but settles on a quasi-Biblical McCarthy-esque view of the darkness inherent to man’s soul. Unlike many novels coming out of the dissident right literary sphere, Herod’s book contains no speechifying or proselytization that I can detect, and is accessible purely on its own terms without any contemporary extremely-online context.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about this short novella is that it’s about as well written as many contemporary literary fiction novels, but it’s been self-published. If I had to wager a guess, he probably did not attempt to get this traditionally published and went right to self-publishing on Amazon.

When I think about the categorization of decentralized vs. centralized fiction, I think it’s useful to think about how we can further delineate between the two.

Let’s start by returning to the original theory I wrote about several months ago: if we imagine the journey of a book from inception to publication, we can simply posit centralized and decentralized versions of each “checkpoint” in the process (in self-publishing, the agent/editorial steps are skipped entirely):

Now, let’s map the journey of Herod’s book from inception to publication using the checkpoint model diagrammed above:

Decentralized step: Herod writes his novel on his own, without any institutional support or backing. (Hypothetical centralized alternative: MFA writing program).

Decentralized step: Herod skips sending out his novel to literary agents, knowing that no matter where he goes, all but a small handful of agents (and their interns) are interested in a thematically McCarthy-esque novel like this.

Decentralized step: Perhaps he had a close friend or several give feedback on a beta version of the book, but he also skips the editorial checkpoint of an institutional editor, which can sometimes act as a homogenizing filter on literary production.

Decentralized + Centralized step: Amazon is a uniquely paradoxical platform—it’s both a classical monopolistic platform chokepoint but also historically a de-centralizing force for alternative fiction. While Amazon has engaged in substantive literary censorship in marginal cases, whether due to commercial reasons (the cost of strictly moderating fiction for wrongthink is simply too high) or due to legal reasons (first amendment-related), Amazon has largely left alternative fiction alone. This has been true for quite some time and my prediction of Amazon leaning into LLM-based censorship of books may well prove to be entirely wrong or extremely early. I don’t have a strong view on this yet.

My own novel INCEL has essentially taken the same path as Herod’s book: created outside of the MFA/publishing complex but necessarily published on Amazon due to the enormous advantage it has in distribution.

I think Amazon is a relentlessly psychopathic profit-maximizing company but it’s just so goddamn convenient that, whenever I return to the US, I find myself ordering things on Amazon (especially books!) all the time.

The combination of low prices, speed of delivery, and low-friction one-click checkout really just does make it my default option for book buying even as each individual click I enter into this corporate machine seemingly initiates a Rube-Goldberg-style contraption that appears to have been optimized to maximize the suffering of its workers.

I don’t feel good about this but I’m also addicted to the near-instant gratification of books coming as fast as possible, and I’m literally a guy who’s writing a blog about how centralized publishing is bad (lol).

I’d admonish myself for my own hypocrisy in this regard, except it doesn’t feel like a sin so much as a temporary and fragile state of affairs: so long as Amazon isn’t actively censoring novels (or other books) that interest me, I’ll continue to order physical books from it (I try to avoid Kindle orders since you obviously can’t trust anything digital these days, since DRM prevents actual digital ownership).

When I look at an alternative model like Canonic.xyz or Expat Press (both of whom I believe print their own books), I just don’t know how they can even achieve a micro-cosm of Amazon-style scale. There are, of course, other niche publishers that do perform their own printing and distribution, but the economies of scale available to Amazon for the printing and distribution are simply overwhelming.

Ironically, I could see a scenario where Amazon brings the hammer down on various forms of dissident or alternative literature, thereby boosting this market of individual micro-publishers like Expat to a much greater degree.

So—if platforms don’t actually care about the content of most literary fiction, then why does the current level of sameness persist?

The simplest way to think about it is as a kind of distributed conformity:

Here’s a challenge you can, just if you’re curious: skim through the descriptions of the preferences of the first 10 or 20 literary agents that you can find who work in traditional literary publishing.

If you have any capacity for intuition, you’ll find that they have highly similar aesthetic filters.

The point being: it doesn’t matter how many nominally-decentralized agents (and small publishers) there are if they all filter content in the same way.1

What is needed to press forward isn’t merely one set of parallel literary institutions (agents, publishing houses, literary magazines, and a commentariat), but an entire ecosystem of them.

That is why I am excited to see alternative literary spaces grow, no matter their stripe—there’s a certain macro-level utility to this kind of cultural chaos, because it opens up new niches for outsider artists to bloom. As I said in my first podcast episode, while I don’t entirely dismiss the analytical framework of art as being capable of causing harm (e.g. GWOT war propaganda movies), I think literary fiction is a special case where, even if that was an active consideration, the risk of genuine harm is wildly overstated, and the value of generative cultural energy is wildly understated.

I am now midway through my life, but fiction is no less enthralling for me than it was in my youth. I want to read as many great works as I possibly can—and not merely great works of eras past. I want to see greatness now, and I believe that we can once again capture that energy and, through the evasion of chokepoint-gatekeepers, amplify and nourish it.

For something truly suis generis to be born in the literary sphere, it must necessarily come out of some degree of chaotic rejuvenation.

Thanks for the kind words on Improvidence, and you're correct in assuming I did bother shopping around for an agent!

Traditionally this would get packed into an anthology with a few short stories, but I really wanted to put improvidence out there as a single tight story that someone could breeze through in a weekend.

My idea was that as a new writer, length actually works against you since people are unsure if they'll love your work. So a cheaper cost of production (passed on to buyer by Improvidence's low final price) and a more guaranteed feeling of "hey I finished a book" would hopefully make people more willing to take the leap of faith to read my stuff.

The alternative is to put out work for free and follow more of a web novel monetization strategy (which I plan to try for my next project).

Just bought it based on your review.