Podcast appearance - Hacking State

Talking meaning in a post-meaning world

Recently, I had the pleasure of appearing on Alex Murshak’s podcast, Hacking State.

You can listen here:

Murshak is a very sharp guy and was a very thoughtful interviewer—while he’s not a pseudanon himself, he and I travel in adjacent circles, and I felt we had a great discussion about a number of topics.

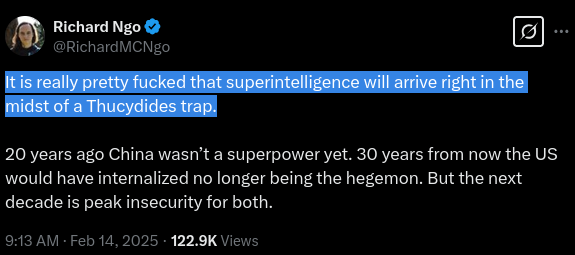

The interview sort of naturally converged on this topic of meaning in an accelerationist age, which I think will be an increasingly salient topic in an age of mass technological unemployment, technofeudalism, and severe social disruption (this is my base base for the next 5 to 10 years, contingent on a slow takeoff for AGI—in fast takeoff, I agree with the EA’s and I think there’s a non-trivial chance we’re all dead).

In short: “Land was right.”

In any event, perhaps it’s because I sense an impending wordcel apocalypse that I’m so fixated on the risk of human beings (and literary artists) being usurped by machines.

At this stage, I would be very surprised if LLM’s don’t supplant vast swathes of white collar work at minimum. I use these tools on a daily basis and they have already eliminated a lot of human labor from my own regular activities. At minimum, MBA’s, analysts, most knowledge workers—these people are facing an extinction event (if you’re a skeptic, try OpenAI’s ‘Deep Research’ and get back to me).

A lot of what will drive human disempowerment and loss of agency is going to be driven by AI and the attendant technofeudal order of things.

For those of you who are interested in reading more about the centralization of power from Silicon Valley tech barons, I would suggest Yanis Varoufakis’ excellent Technofeudalism, which is an interesting complement to Peter Thiel’s Zero to One (in which he famously argued that a good startup should strive to be a monopoly).

The simplest way to think about frontier closed-source American AI labs (with the exception of Meta) is that they’re centralized systems for collecting economic rent.

There’s something deeply ironic (and hilarious) about a conflict between a liberal democracy pursuing hegemonic planetary control via closed-source AI and a communist country deliberately diffusing open-source AI as a countervailing geo-economic strategy.

The former system is designed to produce a near perfect-system of perpetual rentier capitalism while the latter system diffuses powerful AI systems into the hands of regular people world-wide.

(Of course, each branching pathway comes with numerous risks).

Thus, I increasingly find myself fixated on what I view as the essential fulcrum of history:

More and more, you and I will be hearing about the importance of “beating China on AI.” As they race toward catching up on semiconductor manufacturing (the export controls won’t work in the medium-term), we are already seeing the groundwork laid for an escalation in conflict above-and-beyond existing export controls:

In the domestic Western context, my base case is a radical centralization of power in the hands of various American AI companies and the Silicon Valley military industrial complex. There will be escalating purges of Chinese STEM researchers and various efforts to ban or contain the diffusion of Chinese AI systems (and robotics in particular, I think).

In the US, I am not sure that sophisticated propaganda systems are even necessary once you factor in the economic disempowerment that is likely to occur—how much power do you have if you’re economically worthless? They’ll give us video games, porn, AI companions.

(If we’re lucky, survival-level UBI).

What’s the future, then?

It’s Houellebecq and then William Gibson, in that order—and we are all along for the ride.

Why should literary artists care about this at all?

If you strive to write about contemporary life in literary fiction, you’re effectively presenting a world-model.

What this means, in effect, is that the scope of that world model can be as narrow or wide as you want it to be.

The novel doesn’t merely capture a slice of consciousness: it captures that slice in the context of a setting (a world-model).

Thus, a work of a certain scale relies on the writer accurately understanding the world that he or she lives in.

And, as I look toward confronting my next book—which I’ve been too busy to even start—I find myself driven by curiousity more broadly. This is even in spite of my own technical ignorance on these matters.

May you live in interesting times, my friends.

Coda: Some interesting posts from Murshak

His own writing is, I think, underappreciated. Check these out:

Great recommendation with Varoufakis, one of my first posts (now deleted) was about Technofeudalism. His explainers on world events since publishing that book have kept me sane through the white noise of US news, especially most recently on Trump and his intended strategy with tariffs.

Trump might try to shock, but China won't be in awe anymore during his second term. They have accumulate enough Chinese AI expert that were educated in the States but couldn't get a H1B visa to stay.