Online pseudonymity and the post-facial author: the alt-lit case for peeling off your face

Building off of Balaji Srinivasan's model of the internet is a PvP zone: pseudonymity, tradeoffs, identity silos, and the conduit theory of art

The internet is a PvP zone.

When I was young, they used to call it cyberspace. They didn’t tell me, however, that in this space there are countless people who want nothing more than to hurt you and destroy you, regardless of your ideology, identity, or moral tribe—no matter your stripe, you will find a group of people who want to annihilate you and whatever work you’re doing. For every axis of human beings, you’ll find two opposing poles, each of whom is violently opposed to the other’s existence. Because of memetic replication dynamics, most belief systems are implicitly totalitarian, but spite doesn’t need ideology to sustain its existence; the infinite capacity of human pettiness is more than sufficient fuel for an infinite procession of digitized vendettas.

Because you can’t punch somebody in digitized space, the medium’s categorical negation of violence paradoxically allows for the closest approximation of a truly Hobbesian state of nature.

The internet, dear friends, is hell, and the purpose of hell is to inflict pain and suffering on all of its inhabitants.

Despair not, friends. We are nonetheless having a great time out here, because any sort of Darwinian game invokes a thrill in the player.

“If you die in the metaverse, you die in real life,” as they say. Stakes are a necessary ingredient in any viable dramaturgy, after all.

Rather, it would be more accurate to say that the internet is a high variance environment—with implications for both the good and the bad. In any environment, there are natural advantages that accrue to either offense or defense, and in the case of being a public writer (again, of any stripe), the advantages accrue to the offense.

As a public writer, your identity is a fixed point in cyberspace, an open attack surface, while your attackers are spatially distributed and cloaked behind a natural asymmetry in favor of offense. Even comically anodyne figures like Tim Ferriss, by virtue of the law of large numbers, attract profoundly disturbed assailants. This is the flipside of being able to distribute your work at scale, and it is a tradeoff that I (along with every other writer) have tacitly accepted.

Okay—I’ll stop being circuitous (it’s always annoying to read people who write like that).

Here’s my position on having a face: it matters tremendously, but it’s completely worthless, both at the same time.

PSEUDONYMITY: Simple and practical benefits

I’ve been a fan of Balaji Srinivasan ever since he correctly predicted the magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic while every prestige media organ was downplaying it as a nothingburger. I generally dislike VC’s and crypto ones in particular, but he’s an exception and produces a quite a few interesting ideas.

I’ve seen many good critiques of his Network State idea but I think it’s still generated a lot of valuable discussion around how technology is going to radically inflect all of society in the direction of increased weirdness. I believe that the future of fiction is decentralized, and that crypto will also play a huge role in this (more on that in future posts).

Vis-a-vis the state of modern fiction, there’s a fantastic talk that he gave a couple of years ago that is one of the more far-sighted takes I’ve seen on online pseudonymity and how societies and economies are going to work as humanity accelerates toward the concrete wall of the machine apocalypse.

This is going to sound a little bit crazy, but I think this venture capitalist has a lot of good ideas about pseudonymity and alternative literature.

It’s short, and you should absolutely check it out:

Let’s start with the general: as a writer, there’s enormous power in having a face, because having a face drives parasociality between you and your fans, and paraosicality is maybe the most important driver behind building a modern audience.

Even before the internet, public interest in the personal life of a famous novelist has always acted as a fuel for their audience—Bukowski’s writing is even more interesting because we know who he is. Imagine, for a moment, Bukowski as a contemporary writer in our networked age: imagine him alive, doing YouTube interviews, live-streaming and sharing about his life while pounding glasses of scotch and chain-smoking cigarettes. It would be riveting.

Like anybody else, if I’m listening to hours and hours of some guy talking on a podcast—he becomes my asymmetric friend. When I see Houellebecq doing an interview, with this wry little shit-eating grin on his face, leaning as hard as possible into his chain-smoking, French Eurotrash aesthetic—I think to myself, I love this man. What a goddamn comedian (yes, I’ve read all his books, obviously).

Pseudonymity severs that connection: it peels your face right off. The mob doesn’t know what to do with this; it needs a face to love you with and a face to hate you with.

As Balaji points out, it does, however, have certain benefits.

1) Mitigation against spatially-distributed mob attacks

Friends, you and I are already living in a panopticon; it’s called everyone else on the internet.

The first benefit to pseudonymity is merely that spatially-distributed mobs can’t come after you as easily. What this means, in practice, is that it’s harder to get hate mail; it’s harder to fire you; harder to un-bank you; most importantly, it’s harder for someone to physically kill you.

Is this relevant to novelists?

Yes—that personal safety might be a concern for a novelist sounds absurd; of course, Rushdie is a massive outlier, but is he, really?

If you know anything about the internet, the threshold for someone trying to kill you (directly or indirectly) keeps dropping, largely because we live in a deeply sick society that is increasingly populated with violent and unstable people spanning the entire ideological spectrum.

This isn’t a left/right phenomenon anymore, it’s a sick-society phenomenon. The United States and the entire Western Anglosphere are socially disintegrating; it is extremely unlikely that we will ever see this trend reversed, largely because it’s a by-product of technocapital and financialization, two trends that are appear unstoppable in the West.

In general, this category of risks is incredibly random and even everyday people can get swept up in these sorts of mob dynamics (much less a writer of modern fiction, who is attempting to call attention to themselves). Remember that anytime you see artistic “transgression” being celebrated by some public-facing literary journal or institution, it’s certain to be anything but; in some dimensions, we are writing in the most pious era of art in recent memory.

2) Mitigation against the purity police

Balaji, being a systematizing thinker, has this hilarious two-part infographic where he diagrams how the press cancels people, which he terms “supply chain social disruptions:”

Then, he explains how pseudonymity can shield against this sort of attack:

With a fiction author, it’s a little bit more complicated, since some authors will have an anti-fragile readership and controversy will drive more attention and sales. But for most authors, having a journalist write a hit piece about you and your art has the potential to seriously fuck up your life and your career.

Success in literary fiction is a function of social networks and getting cut out of professional networks can absolutely destroy everything you’ve built if any part of your success is reliant on institutional support.

In this environment, if you are writing transgressive fiction—institutional support is a massive attack surface and a one-shot kill that can be used against you at any time.

Some have argued that purity-police hit-pieces against writers are becoming less effective as the US bifurcates into two increasingly polarized cultural factions and it becomes harder for the left to cancel the right and vice versa, but I only partly agree with this hypothesis.

Instead, what’s going to happen is that the 2024 election will be intensely destabilizing and break the core legitmacy of the electoral system; as a result, the culture war will accelerate and this kind of purity policing will only become more vicious. The battle over the Aesthetic Overton window is only going to intensify further. The threshold for being “cancelled” will continue to drop as institutional anxiety about the coherence of the entire politic (rightfully) increases, and there are no shortage of journalists willing to take scalps in exchange for accruing clout of their own in the Thunderdome of the modern internet.

It is only a matter of time until interesting alt-lit fiction authors are booted off of Amazon and other centralized platforms. Why am I so pessimistic? Well, they’re already trying to cancel SubStack, for fuck’s sake.

We need to prepare for this day because the main thing preventing this from happening right now is merely the obscurity of alt-lit, and even if I’m wrong about the culture war’s imminent escalation, obscurity alone will be insufficient when advances in algorithmic moderation dramatically lowers the labor cost of censorship on centralized platforms. Soon, it’ll soon become much cheaper to algorithmically censor writers using LLM’s and the like.

3) Pseudonymity liberates you from facial constraints

A profile picture is a costume, but it’s v1.0 of what a costume will be as compute gets cheaper and AI gets better. Swapping out your RL face is liberating, because it’ll free you to assume whatever form you want, and to switch this form.

Why does this matter for the alt-lit author?

It matters because it’s fun, and having fun is a prerequisite for doing good work. It also makes it much, much harder to take yourself too seriously, which is the more important benefit.

So much of boringness in modern literature is a function of this oppressive seriousness. Everything feels like a weighty moral psychodrama, and we are always feeling burdened by the gravity of it. Every blurb about xyz-new-novel is about how “urgent” and “important” it is. I too, am partly guilty of this, but I reject the idea that levity is antithetical to serious work. If anything, it makes serious work substantially more digestible. Tragedy is a knife’s edge from comedy at all times.

4) Pseudonymity reflects—not deflects—the fundamental reality of artistic identity and its necessary subordination to forces greater than the individual

Here’s where I’m going to take some liberty with what Balaji said and extrapolate beyond the boundaries of his argument alone.

When people say that “there’s an artist inside everyone,” I think this is true, and I don’t think it’s just a metaphor. I think, on some level, that it is literally true. There is, in my humble estimation, a tiny artist-homunculus living inside your brain at all times.

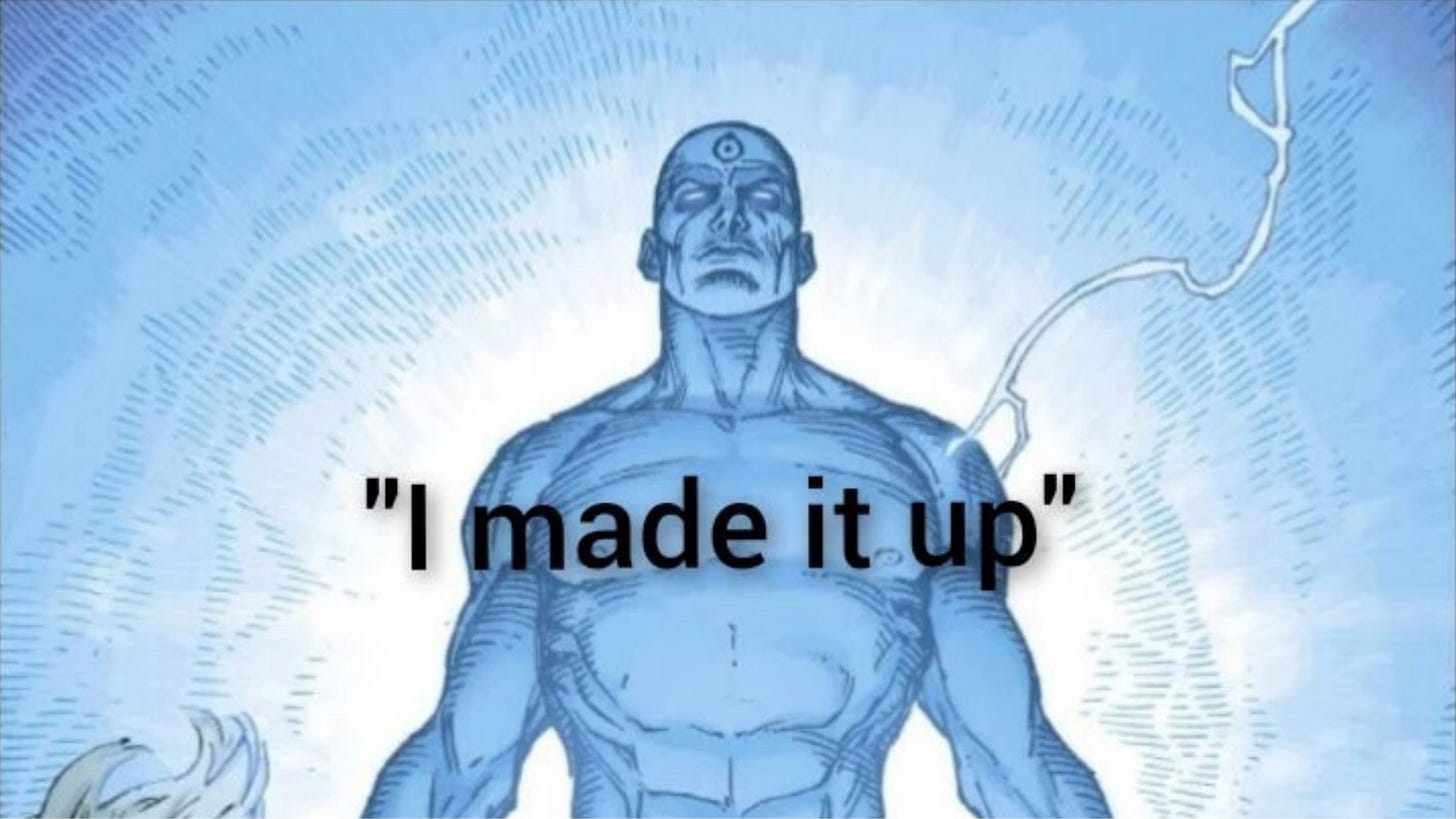

In spite of residing in you, this little homunculus is siloed off from the other parts—siloed off from pride and vanity and always wanting to be liked for your ordinary beauty. The impulse to toward creation is greater than the individual, it subsumes, no—it consumes your autonomy into a localized instance of the universe expressing the will of creation. Yes, dear reader, I need you to know that I am not actually in control as I write this; as with anyone who has ever produced anything, I’m merely an instrument of fundamental forces which span the bridge of time itself, from now until eternity.

What? You don’t believe me? You think I’m being rhetorical again?

You are wrong.

When you silo off your identity as an alt-lit author, when you empty yourself of your petty narcissism and the parties in Brooklyn and the (questionably realistic) “access to e-girls” and the idea of sitting on a panel in a nice bookstore while the moderator jacks you off verbally during the introduction and you make a hilarious quip that everyone laughs at and people in chairs are smiling at you unison and everybody likes/loves/adores you; when you shrink to the non-corporeal form of a pseudonym and crack the pipe of parasociality connecting you to your audience—friend, only then will you have achieved freedom. And it is not freedom “from the consequences” of your speech, as many a midwit has said, but freedom through subordination.

I SAY TO YOU—CUT OFF YOUR FACE, AND YOUR WORDS WILL REWARD YOU.

Do this, and you will have purified yourself before an altar. You will have peeled off the skin and flesh and tendons that make up your face, that make up your mask, because yes, that’s a mask too, and you will have acknowledged yourself merely as a conduit for the force of creation.

You are words, and nothing more; from words you came, and to words you will return.

God smiles upon you for doing this.

You didn’t think you could leave without some shilling, did you?

I’ve recently released a novel about a young proto-incel in the early aughts (note: print versions are temporarily offline). It’s a “realistic satire” about a man obsessed with the complete systematization of human nature under a highly charged ideological interpretation of evolutionary psychology—the kind of broscience that’s fixated on an increasingly discredited version of “dual-mating” theory that’s poisoned an entire generation of men on the internet.

I have, in short, written a book about shame, masculinity, and radicalization.

I won’t lie: even though it’s a dark comedy, it’s a difficult, challenging read. That is the essential nature of any art that is transgressive, and although it ultimately sides against the neo-Darwinian argument for “evolutionary nihilism,” it necessarily contains both thesis and antithesis in this regard—anything less would have been incomplete.

Recently, someone posted a review on Amazon that piqued my interest:

The part that stuck out to me was this notion of success and failure in art. This reviewer was indeed pointing out something important about my book: it is walking a fine line, and it was very hard to write.

These notions of success or failure—as personally constructed by anyone who has ever released a work of fiction—frame every single work of fiction as an attempt, and in any attempt, the person doing the attempting cannot be overly afraid to fail (or else they will not try). Note, also, that the notion of artistic success or failure is entirely orthogonal to the moral manicheanism of the culture war’s all-consuming morality tale.

This is the ultimate utility of pseudonymity: it makes artistic failure tolerable. Regardless of what we say about the production of contemporary literary fiction, we are all lying to ourselves if we say that modern novelists are no longer afraid to fail. They are terrified of failing, because the culture war’s incessant purging has subsumed the production of anything difficult, challenging, or complicated, leaving only the residue of the safe and didactic.

Contemporary fiction has been subordinated to moral instruction; that’s all that the culture is anymore, a form of scolding. Publishing corporations are transgression-annihilators. That being that case, how can you write honestly about fucked up, broken characters?

You can’t.

Second question: how can you narrativize the healing of these fucked up, broken characters, reducing the aggregate psychic pain in the world?

Again—you simply cannot even attempt to do so.

For now, we are paradoxically reliant on the mother of all centralized giga-platforms—Amazon, of all entities—for the cultivation of decentralized fiction.

Look to the future, friends, and you will see that we have our work cut out for us—but despair not! For every great struggle, there is an equal and commensurate quantity of meaning.

I’ll see you on the fields of Elysium.

puts into words what i have been practicing for years at this point, lol. in a certain sense having a """persona""" online (just me minus my face and name) has been freeing. good essay

Nice ideas, ARX. I think the most critical takeaway for me is section 3. I perceive it as "Living through an avatar", a more comfortable way to interact with the PvP zone.