ANDROGENIC LITERATURE REVIEW Vol. 1: Nutcrankr by Dan Baltic

incelcore has arrived as a literary micro-genre

Though it pained Spencer to slightly mischaracterize the quality of Nietzsche’s thought, it appeared as though Crystal was regarding Spencer across the table with mounting dread and anger. And while ordinarily Spencer would have been happy to make bacon of this piglet in intellectual debate, he dutifully held his tongue, maintaining his commitment to the furtherance of the Project. His sole focus right now had to be having sex with Crystal to combat global Marxism.

- Nutcrankr, by Dan Baltic

When I think about culture, I often think of it in terms of cultural evolution.

This is one of the reasons I dislike the term generative art, which is meant to denote only AI-created artistic works. No matter what comes after our species, humans—not machines—have always been the original generators of art. Calling art “generative” is redundant, as is calling any piece of creation “created.” As a species, human beings exist in a constant process of death, birth, and recombination. This is true of nations, cities, communities, families, and individuals.

Tautologically, it is also true of art.

Partly, this is why I don’t believe that the novel is an exhausted art form. So long as human culture continues in its evolution, a new type of guy is constantly getting dropped. We are in a state of constant psychological genesis, constantly generating new personalities (and pathologies). All of these can be stored in narrativized form.

Fiction is a form of bottled consciousness, and the novel is merely a container. As long as we are constantly developing new types of minds—how could we not?—then the container cannot be exhausted.

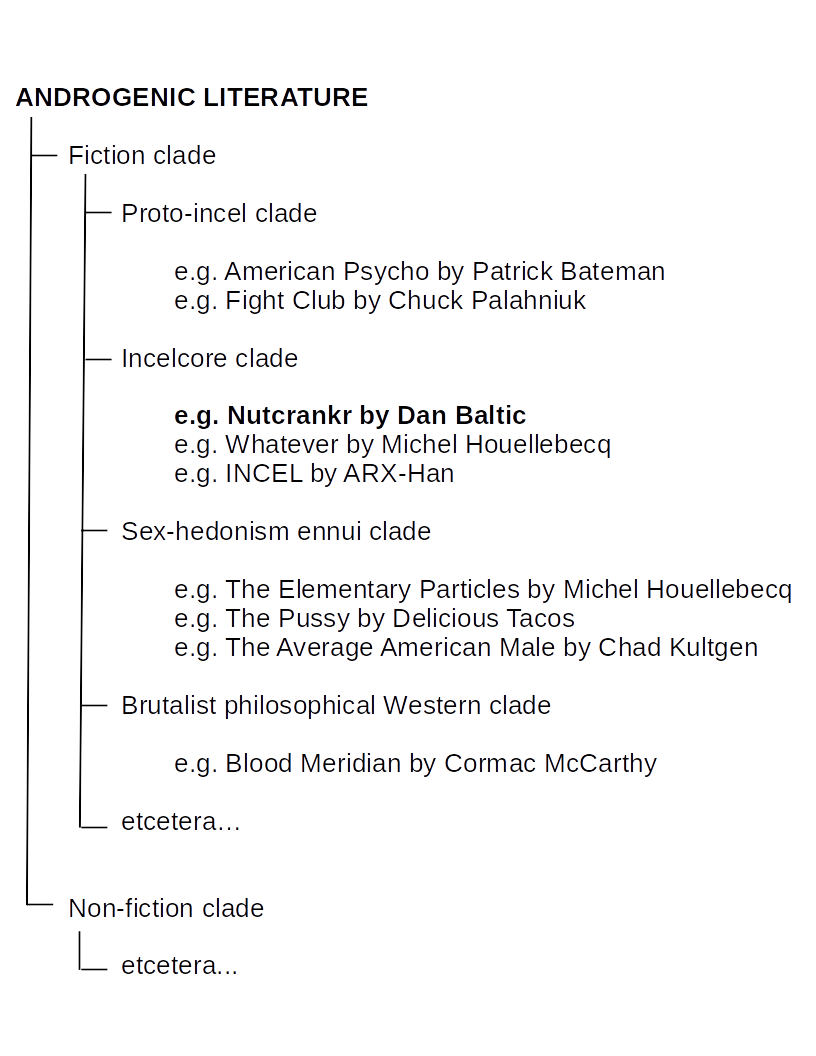

Enter ANDROGENIC LITERATURE and its novel literary sub-clade: fictionalized incelcore.

It is here that we will find Dan Baltic’s Nutcrankr.

Consider the following cladistic diagram for reference:

Let’s start with the basics: Nutcrankr is about a young man named Spencer Grunhauer. He is a young white American male enamored with reactionary politics and the magnitude of his own intelligence. He works at a non-profit and is surreptitiously publishing a complex political treatise in the vein of Mencius Moldbug’s Unqualified Reservations, but with considerably less depth and sophistication than Curtis Yarvin.

Spencer, as we soon find out, is afflicted with a severe case of dramatic irony—a yawning chasm between how he sees himself and how he is seen by others. This basic narrative structure creates a current, an electric charge, which opens the path for Baltic’s ruthless satire of the disaffected American reactionary. While not (always) an incel outright, Spencer’s psyche sits firmly within the broad shape of that categorization, but because of Baltic’s distant, comic perspective, his protagonist comes off as cripplingly funny instead of hard-edged and dangerous.

It is, in short, a book about male alienation, compensatory narcissism, and the mind’s instrumentalization of ideology. Beyond his self-identification with the right wing, I’m not aware of Baltic’s personal politics to any degree of depth, and having read his novel, I would say that I am no closer to knowing what he truly believes. This is a compliment—not an insult. Baltic is conscious of the primary problem with contemporary literary purity culture—it’s fixation on moral didacticism—and despite being right wing himself, his novel is a deeply funny critique of the relationship between masculine ego and ideology. That he studiously avoids any type of lecturing demonstrates restraint and good judgment as an author.

At bottom, Baltic has a good grasp of male ennui and all of its extremities: an entity that can be reliably framed within the perspective of the absurd. He is distinct from Houellebecq in that his book isn’t nearly as tonally dark; unlike our beloved, morbidly depressed Frenchman, Baltic’s narrative sits further out from the event horizon of total overbearing nihilism. In Nutcrankr, absurdist comedy is the only thing that can emerge from the meaning collapse of modernity, and he succeeds in his literary purpose.

I can confirm, dear reader, that Dan Baltic’s novel is CERTIFIED ANDROGENIC in its workings.

IN WHICH I REPEATEDLY QUOTE MR. BALTIC TO GIVE YOU A SENSE OF HIS NOVEL

There are times when all is well in the world. Spencer experienced such times rather infrequently, due to the pervasive influence of global Marxism.

Whether or not you enjoy Nutcrankr should be immediately obvious within 1-2 pages of reading. This is a voice-driven novel: its propulsion is a function of third person narration that runs on comic energy. I submit to you that you must be sufficiently androgenic (in spirit or in flesh) to find it funny—if you are, then you will likely resonate with its topicality.

Taste, as they say, is determinative in this respect. If this micro-genre is not to your inkling, then this (or any other similar work) will be tiresome and annoying.

What Baltic understands, in a sort of pre-ideological manner, is how funny the average extremely online reactionary is. This is not a celebration of masculinity qua masculinity. It’s a satirical portrait of the millennial ideologue in the early to late aughts, and how profoundly unserious they can ultimately be.

I won’t spoil the (hilarious) ending, but in Nutcrankr, human beings instrumentalize ideology for their own purposes—and never the other way around. In Baltic’s framing, radicalization is largely downstream from the unmet emotional needs of the human male. It’s a simple, resonant thesis, and rings true for me as a writer as well.

To give you a sense of the novel’s voice—AKA it’s narrative “metastructure”—the following sequence of quotes should clearly signal whether or not you will enjoy the book’s satirical analysis of millennial masculinity.

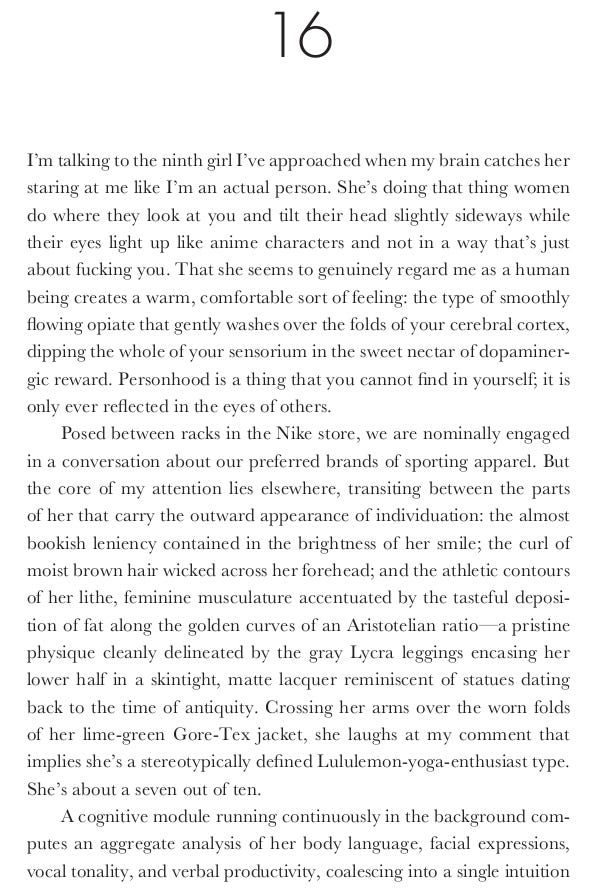

Spencer, like most men, is immediately introduced as deeply pornbrained:

In some ways, they had already consummated their love, sharing a sex of the mind, where the orgasms arrived as clever barbs and the ejaculate as propulsive laughter.

As with many incels or incel-adjacents, male fraternization does not come naturally to him, and he struggles with forming same-sex friendships:

“You drunk already, Spence?” asked Alex. Though it was true that Spencer was a bit under the sway of the premium liquor, he resented Alex’s overly familiar tone. But Spencer knew better than to register offense. Alex was inviting Spencer to the game of masculine jocularity.

He is, similarly, beset with a rather classic case of the Maddona-Whore complex, unable to see women in anything other than binary terms:

Driven by an unerring commitment to sin, Alex drew Nora close and encircled her within his beastly arms. But before he clasped his hands around her waist, he pressed his left palm flush against her right buttock, his meaty paw grasping against the softest surface of the Muse. And though this violation was short in duration, Spencer saw it clearly and eternally. An unholy tableau seared into the recesses of that intricate pulp computer whirring and pulsing between Spencer’s ears.

Spencer approaches writing as many authors do: as a single-player game largely distentangled from external feedback:

Spencer reviewed once more his morning’s labor, reflecting off the glass parchment of his digital stylus: “A Theory for the Equitable Distribution of Wives.” This was an important chapter and Spencer wasn’t certain he had crystalized the methodology for wife selection with sufficient exactitude. But the perfect was the enemy of the good, as the cretins liked to say. Spencer clicked “Publish” and this chapter joined the many that had preceded it on 3Chain, the notorious online message board.

He is punctured with insecurities, which require constant equilibriation with self-soothing internal dialogue:

“Yeah, I was just running late from lunch with a friend,” said Crystal, her full chest shaking in harmony with her prevarications.

It was not in the least appropriate to let a prior social engagement delay a subsequent one. And what type of friend was this, anyway? Was this the type of friend who had deposited semen into her body?

The latter quote is pulled from my favorite part of the novel: a date with one Crystal Clancy (who goes on to become one of the primary characters in the story).

His internal dialogue, use of tactical lying, and the contrast between his thoughts and words carries what is arguably the funniest scene in the story:

“Yeah, I kind of run the Public Affairs Department at this place called the Center for Social Advancement,” said Spencer, gently massaging the truth in order to convey a greater truth. In fact, Spencer did run a marketing department—as well as a legal department, editorial department, and business development department of a little company called the Project!

His opinions are a mish-mash of Jordan Peterson style patriarchal traditionalism, monarchism, boomercon hawkishness & Sinophobia:

“No, Spencer, I don’t think we should go to war with China,” said Hunter.

This unfair characterization of Spencer’s honest attempt to discuss a Western response to China (which should include, but by no means be limited to, military solutions) was met with disrespectful laughter from the great minds congregated within the Toyota Siena.

Lastly, like many self-published authors, he is also a victim of de-platforming and centralization:

The prospect of starting a new 3Chain account and republishing the treatise seemed both unpalatable and Sisyphean. It would take months or even years to rebuild his follower count, and why should he?

Let me be clear, dear reader: I recommend Dan Baltic’s novel, Nutcrankr, to anyone and everyone who is interested in this type of guy.

CODA: Convergent evolution in the literary sphere

Now—this wouldn’t be a de-fic blog post without me doing a little bit of shilling!

One of the things I find incredibly interesting is how two authors can write a novel about essentially the same topic and person but can do so in a completely different style. The resultant outputs are as radically different as they are the same—that is to say, mirrors and divergences.

Baltic’s treatment of the incelcore micro-genre proves the point of convergent cultural evolution: we may have taken completely different paths, but we have ended up in much the same place. To me, this is what is so fascinating about art: it’s inevitably highly individualized—especially fiction—because no two authors can produce the same fictionalized stream of consciousness. This is what it means to be human, to be generative. Mimicry is more difficult than something sui generis.

Whereas he primarily leans comic, I alternate between satire and a darker realism. Whereas he leans toward precision and brevity with regard to description and exposition, I lean into maximalism and over-description as a style. Whereas he frames ideology as largely subordinate to man, I have them trading places. We both rely heavily on a narrative voice tuned to the millennial reactionary’s preferred aesthetic orientation (to an absurd degree: our protagonists both rely on Nordic pseudonyms when posting online!).

No one approach is better than the other—these are simply the natural permutations artistic (and human) differentiation.

I love to see it, frankly.

For comparison, I’ll leave you with a short excerpt from my novel that captures both its similarity and contrast to Baltic’s thematic lanes and literary style:

You can find Mr. Baltic on Twitter here, and on SubStack here.

Much like one Spencer Grunhauer, he draws vital energy from posting on the internet on a frequent and regular basis.

Reading both books this month the parallels between the two is surprising, agree that no two people can write the same book which is a really wonderful thing

I finished reading NUTCRANKR as the second of the Androgenic literature you've recommended, and I must say I loved this book. It successfully towed a fine line between horror and comedy, which both revolved around the main character Spencer's total inability to properly assess other people's thoughts and reactions, his over-the-top view of himself (I loved that the line kept being repeated that he was "a graduate of one of the nation's more highly esteemed liberal arts colleges") and contrasted with his actual willingness to accept the thin gruel of the bottom of society (a relationship with a formless, unattractive, politicized ultra-feminist who he repeatedly calls, hilariously, the piglet - but only to himself). I think society's unrelenting atomized nihilism was mostly incidental to this story, whereas it formed a key component of "Incel" - here is mostly a character study along the lines of a Don Quixote mixed with an Ignatius J. Reilly updated for the modern era. Both approaches work.

This paragraph stood out to me: "It was much better to conceive of woman as a nighty piglet. Does one raise the piglet to the sky and bow down before its squealing form? No one towers above the piglet, giving it a pat on the head and a swat on the side. And if the porker tracks mud or waste into the home? Then the farmer takes the belt to her fatty rear! For the piglet is by nature buoyant and mischievous, given to chaos if untended or untrained. Treat a piglet like a princess and one's home will more resemble the sty than the castle. And where goes piglet, so goes woman. Provide woman the same discipline one provides the pig and one shall see a happy union. And what's more, Western man shall stride one step closer to final victory over the Marxists in our midst."

The scene where Spencer tries to get his NUTCRANKR account back and is quizzed by the receptionist was a standout of comedy, I think.

Lastly, a couple other points: I didn't like the title nor the cover art, as I think neither captured the core of what the novel represented (you nailed both with Incel). Also, it was interesting to see the novel told in third person vs. Incel's first person narrative - I think first person here would've been stronger. The ending was hilarious and unexpected.

Thanks for recommending it.